Error: No layouts found

A look at Montefiore’s innovative wound-care program and an Einstein researcher’s promising wound-healing therapy

Like many other people with sickle cell anemia, Joseph Peay, 57, of Elmhurst, Queens, has battled chronic skin ulcers for much of his adult life. The wounds, on both ankles, appeared spontaneously some 25 years ago—one the size of a quarter, the other larger than a silver dollar. Both itched, oozed and ached. “The pain was so bad at times I couldn’t even put my feet on the floor,” he says.

Mr. Peay sought care at a local hospital, where doctors removed dead and dying tissue that could promote infection or interfere with healing, in the process known as debridement. The pain eased a bit, but the wounds remained raw and troublesome.

“I called the wounds my ‘babies,’” says Mr. Peay, who somehow maintained his sense of humor over the years. “I had to change their dressings every day—and it seemed like they would never grow up and move out.”

There were dark moments, too. At one point, his caregivers hinted that amputations might be inevitable. “That really got me scared. I couldn’t imagine life after that,” says Mr. Peay, a New York City police officer at the time.

His prospects improved a few years ago, when he found his way to Montefiore’s Wound Healing Program. Since his wounds had resulted from sickle cell anemia—a red blood-cell disorder curable only by bone marrow transplantation—he knew his leg ulcers would probably never go away.

“I was just hoping Montefiore would get the wounds under control, to the point where I could live with them comfortably,” Mr. Peay says. He is now participating in a new and unique program: the Sickle Cell Disease Leg Ulcer Clinic, a collaboration between Montefiore’s Wound Healing Program and its sickle cell clinic.

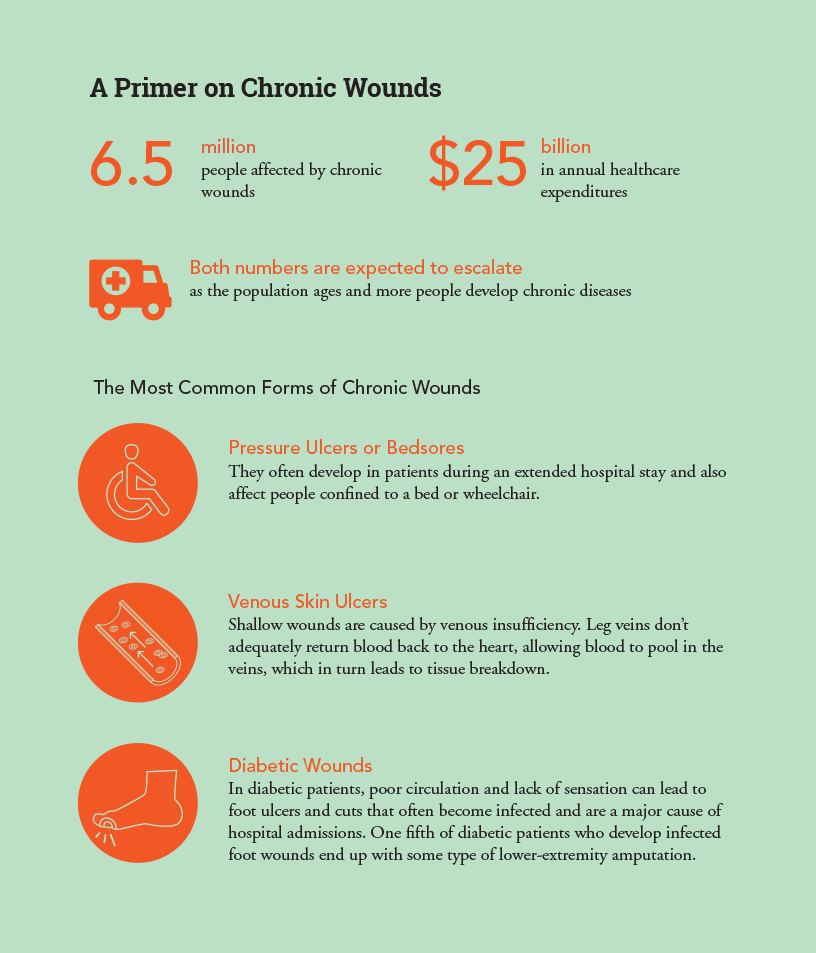

As Mr. Peay’s situation suggests, chronic wounds rarely afflict otherwise healthy people. Instead, they’re often unfortunate consequences of common health problems. For example, the foot numbness caused by neuropathy—a complication of diabetes—encourages foot ulcers that may become chronic wounds. People with impaired mobility, including the elderly and people bedridden or in wheelchairs, may develop pressure ulcers (bedsores) caused by pressure over a bony prominence that can be aggravated by obesity. (The actor Christopher Reeve, immobilized due to a spinal cord injury, died from an infected pressure ulcer.)

Chronic wounds affect an estimated 6.5 million U.S. patients, and treating those wounds costs more than $25 billion annually. With risk factors for chronic wounds on the rise—growing numbers of the elderly and surges in the incidence of diabetes and obesity—it’s no surprise that the burden of treating wounds is increasing. A 2009 report found that the number of hospital patients who develop pressure ulcers had increased by 63 percent over the previous 10 years, and that nearly 60,000 deaths occur each year from hospital-acquired pressure ulcers.

Montefiore’s wound experts tried nearly every available therapy on Mr. Peay’s wounds, from special salves and dressings to skin grafts. Some failed but others helped, and after a few months his wounds improved and stabilized.

“For the first time in years, I had some hope,” says Mr. Peay, who still makes periodic visits to the Wound Healing Program. “The people at Montefiore seemed genuinely interested in finding a way to help me. I’ve got other serious health problems related to sickle cell disease. Now I have one less thing to worry about.”

Stories like Mr. Peay’s are routine at Montefiore. Its Wound Healing Program offers an unusually comprehensive and coordinated approach to wound care, including preventive screening, early detection and aggressive treatment in settings ranging from the hospital to patients’ homes.

Stories like Mr. Peay’s are routine at Montefiore. Its Wound Healing Program offers an unusually comprehensive and coordinated approach to wound care, including preventive screening, early detection and aggressive treatment in settings ranging from the hospital to patients’ homes.

The Montefiore program considers chronic wounds in the context of a patient’s overall health history. As noted earlier, those wounds almost always have an underlying cause—usually a preexisting medical condition but sometimes a change in the patient’s environment such as a new wheelchair, poor nutrition or inadequate self-care.

“It’s critical that we learn the patient’s story—what we in medicine call the patient narrative,” says Anna Flattau, M.D., who is a clinical assistant professor of family and social medicine at Einstein and served as director of the Montefiore Wound Healing Program from 2007 to 2015. (A search is under way for her successor.) “The appearance of the wound is just the latest chapter in that story. Knowing patients’ stories allows us not only to care for the wounds themselves, but to try to alleviate the health conditions or other problems responsible for those wounds.

Anna Flattau, M.D. (right), and physician assistant Cary Andrews bandage a patient’s leg.

“The typical model for wound care is an outpatient center with a high patient volume,” says Dr. Flattau. “That model might be good for business, but it makes for substandard care. That’s because chronic wounds by and large affect the frail elderly, the disabled, the obese—the very people who have trouble getting around. For them, a weekly appointment at the local wound clinic can mean a four- or five-hour ordeal of traveling back and forth. As a result, many patients miss appointments and don’t get appropriate care.”

Montefiore’s innovative approach ensures that chronic-wound patients get care where they need it, when they need it. If patients can’t come to the hospital for outpatient care, the program’s staff coordinates with homecare nurses to make sure care is delivered where patients live.

“They go into patients’ homes like the Marines, examining everything—not just the patient but also the bed, the chairs, looking for anything that might contribute to pressure ulcers, for example,” says Dr. Flattau, who now serves as a senior assistant vice president at NYC Health + Hospitals while retaining her academic role at Einstein. She notes that the wound-care staff also works with clinicians in Montefiore’s outpatient clinics, inpatient services and long-term care facilities.

For Dr. Flattau and her staff, it’s not unusual to see new patients who’ve been suffering from a nonhealing wound for years or—as in Mr. Peay’s case—decades. “Even after all that time, once we get them the right care, many of those wounds can be healed or at least significantly improved,” she says.

Patient-care technician Martha Fonseca with a young patient.

A major goal of wound care is preventing wounds from turning into calamities. That involves identifying those people at risk for developing chronic wounds and treating them aggressively.

A major goal of wound care is preventing wounds from turning into calamities. That involves identifying those people at risk for developing chronic wounds and treating them aggressively.

“With proper care, we can heal a small pressure ulcer in a couple of weeks,” says Dr. Flattau. “Without that care, the patient is likely to become septic or develop a bone infection, requiring a hospital stay and perhaps even surgery. Then you have a huge and costly problem.”

Such scenarios are common in poor urban areas such as the Bronx, where rates of risk factors that can lead to wounds—chronic conditions including obesity, diabetes and sickle cell disease—are well above average. The Montefiore system alone has more than 8,000 patients with diabetic neuropathy, and about 15 percent of them develop foot ulcers each year.

“So we’re talking about a lot of patients at risk,” says Dr. Flattau. “The amputation rate for people with diabetes in the Bronx is twice the rate in Manhattan, which says something about the gap in care that we need to address. We can’t prevent all of those ulcers, but we can prevent many of them.”

Montefiore’s Wound Healing Program is beginning to make a significant dent in the problem. Last year, there were about 800 outpatient visits to the wound-healing program, which also cared for about 2,000 inpatients—remarkable numbers considering that the program’s clinical staff consists of just four physicians, three physician assistants and a medical assistant.

“We’re able to take care of so many patients by using existing resources and partnering with staff in plastic and orthopaedic surgery, rehabilitation medicine, the spinal cord clinic, hematology, rheumatology, endocrinology and home care,” says Dr. Flattau.

Montefiore’s comprehensive array of wound therapies includes cleaning and debridement, antibiotics, compression wraps (which increase blood flow in the legs), skin grafts, nutrition counseling, pressure redistribution mattresses, physical therapy and orthopaedic aids such as custom-made shoes. The program also offers the latest wound-healing technologies, such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy (which helps heal wounds by increasing oxygen levels in the blood) and biologic treatments (such as factors that stimulate cell growth).

But more than any single therapy or service, what really counts is comprehensive, coordinated wound care. And that, says Dr. Flattau, requires changing an institution’s culture, so that seemingly simple but crucial measures—routinely assessing patients at risk for pressure ulcers, turning patients frequently in hospital beds to relieve pressure on the skin—are adopted.

“At Montefiore, we’ve seen a huge shift in the importance that our physicians now give to treating pressure ulcers, the most common type of chronic wound,” says Dr. Flattau. “At the same time, our nursing staff has made great strides in preventing hospital-acquired pressure ulcers in our patients.” She notes that from 2013 to 2015, the rate of pressure ulcers among Montefiore inpatients dropped 66 percent, falling lower than the national average.

“There are a lot of clinical processes that you can’t measure well,” says Dr. Flattau. “But if your pressure ulcer rate plummets, you know you’re doing something right.”

Those improvements have attracted attention. In 2012, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services gave a highly competitive Innovation Advisors Program Award to Montefiore’s Wound Healing Program—part of a nationwide initiative to test new models of payment and healthcare delivery. The staff is using the award to develop ways of measuring outcomes stemming from its comprehensive model of wound care. The program also won a grant from the New York State Department of Health to develop ways to measure processes and outcomes specific to pressure ulcer care for inpatients.

Unfortunately, the healthcare community is paying scant attention to the worsening wound-care crisis. U.S. medical schools offer students little education about wounds and how to care for them. Many hospitals lack a dedicated wound-care service. National board certification and official fellowship training programs in wound care don’t exist.

“It’s disconcerting that a common, disruptive and potentially fatal health issue such as chronic wounds isn’t a formal component of teaching and training and care in medicine,” says Dr. Flattau. “Some say pressure ulcers are a nursing issue, and to some extent they are, since nurses are best positioned to do a lot of the prevention and care related to wounds. But you need other clinicians to do debridement, order antibiotics and assess for bone infections, systemic disease and nutritional status. Again, it’s the team approach.”

Montefiore’s wound-care specialists are trying to spread their knowledge by offering electives for medical students and rotations for family medicine residents and geriatrics fellows.

“When I look back at my residency in family medicine, I have very little recollection of patients with pressure ulcers,” says Dr. Flattau. “Statistically, a lot of these patients must have had chronic wounds. We just didn’t look. It wasn’t on the problem list. That’s a part of the culture and practice of medicine that needs to change.”

David Sharp, Ph.D., and postdoc Rabab Charafeddine, Ph.D., conduct wound-healing research at Einstein.

The way chronic wounds are treated hasn’t changed much in recent decades—certainly nothing comparable to the advances in HIV/AIDS (combination therapy), heart disease (minimally invasive surgery) and cancer (targeted therapy). But wound care may soon have its day, thanks to David J. Sharp, Ph.D., a professor of physiology & biophysics and of ophthalmology and visual sciences, and his Einstein colleagues.

The way chronic wounds are treated hasn’t changed much in recent decades—certainly nothing comparable to the advances in HIV/AIDS (combination therapy), heart disease (minimally invasive surgery) and cancer (targeted therapy). But wound care may soon have its day, thanks to David J. Sharp, Ph.D., a professor of physiology & biophysics and of ophthalmology and visual sciences, and his Einstein colleagues.

Dr. Sharp studies microtubules—long, slender structures that provide cells with a skeleton of sorts and help them divide, change shape and move. Defects in cell migration have been linked to various diseases, ranging from mental illness to metastatic cancer, but relatively little is known about the molecular mechanisms that control this process.

Several years ago, scientists found evidence that microtubules are at least partly regulated by enzymes that sever them, essentially putting a brake on cell migration when necessary. This suggested the possibility of boosting cell movement—a key component of tissue regeneration—by blocking the action of these enzymes. But which ones?

In 2012, Dr. Sharp found that the enzyme fidgetin severs microtubules during cell division. (Fidgetin is a product of the fidgetin gene, first identified in a mutant strain of mice distinguished by fidgety behavior.) He hypothesized that the enzyme might also have a role outside cell division. Indeed, the following year, he found that fidgetin severs microtubules in nerve cells and that blocking fidgetin’s action promotes nerve regeneration.

In 2014, Dr. Sharp broadened his studies to include skin cells. Working with mice, Dr. Sharp’s postdoctoral fellow Rabab Charafeddine, Ph.D., discovered that another member of the fidgetin enzyme family—fidgetin-like 2 (FL2)—severs skin-cell microtubules. “This suggested that if we could target FL2, we might have a new way to speed the movement of skin cells to injury sites and promote wound healing,” Dr. Sharp explains.

With Joshua D. Nosanchuk, M.D., a professor of medicine (infectious diseases) and of microbiology & immunology at Einstein and an attending physician in infectious diseases at Montefiore, Dr. Sharp found a way to block FL2 using silencing RNAs (siRNAs) specific to the FL2 gene. As their name implies, siRNAs silence the expression of genes. They bind to a gene’s messenger RNA, preventing the mRNA from being translated into proteins (in this case, the enzyme FL2).

To learn more about FL2’s role in humans, Dr. Sharp suppressed its activity in human tissue-culture cells. Those cells moved unusually fast when placed on a standard wound assay (for measuring properties such as cell migration and proliferation). “Wound healing in a living organism is much more complex,” he acknowledges. “But healing begins when skin cells move into a wound.”

By severing microtubules, the enzyme fidgetin-like 2 (FL2) puts the brakes on cell migration. Dr. Sharp has found that blocking FL2 speeds cell movement and thereby promotes wound healing. The skin cell here was treated with an FL2 inhibitor. To assess microtubule dynamics in the cell, Dr. Sharp’s lab fluorescently labeled the microtubules (red) and microtubule end-binding protein 1 (EB1), found only at the ends of growing microtubules (green). The loss of FL2 has increased the number of EB1-labeled microtubule ends near the cell edge, indicating a localized surge in microtubule growth.

The discovery, published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, was not yet ready for the clinic. “siRNAs on their own won’t be effectively taken up by cells, particularly inside a living organism,” says Dr. Sharp. “They will be quickly degraded unless put into some kind of delivery vehicle.”

Fortunately, a solution was literally just feet away from Dr. Sharp’s laboratory. One of his Einstein colleagues, Joel M. Friedman, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of physiology & biophysics and of medicine, had developed a nanoparticle drug-delivery system. It uses tiny gel particles to encapsulate all sorts of sensitive molecules, including siRNAs, protecting them from degradation while ferrying them to their intended targets.

Nanoparticles with their siRNA cargoes were topically applied to mice with skin excisions or burns. In both cases, the wounds closed more than twice as fast as wounds in untreated controls.

“Not only did the cells move into the wounds faster, but they knew what to do when they got there,” says Dr. Sharp. “We saw normal, well-orchestrated regeneration of tissue, including hair follicles and the skin’s supportive collagen network.” The researchers plan to start testing the therapy on pigs, whose skin closely resembles human skin.

Joseph Peay and millions of other chronic-wound patients will be eagerly awaiting the results.