-

-

A Transformed Anatomy Lab Opens at Einstein

A Transformed Anatomy Lab Opens at EinsteinThanks to a $17 million gift, Einstein students will explore the intricacies of the human body using state-of-the art tools and resources

-

Small Teams Are Making a Big Difference in Medical Education

Small Teams Are Making a Big Difference in Medical EducationBy placing every member of a medical school class into one of four houses, each set up with dedicated faculty advisors, the Einstein Learning Communities Program is building a support network for students across their years here and beyond

-

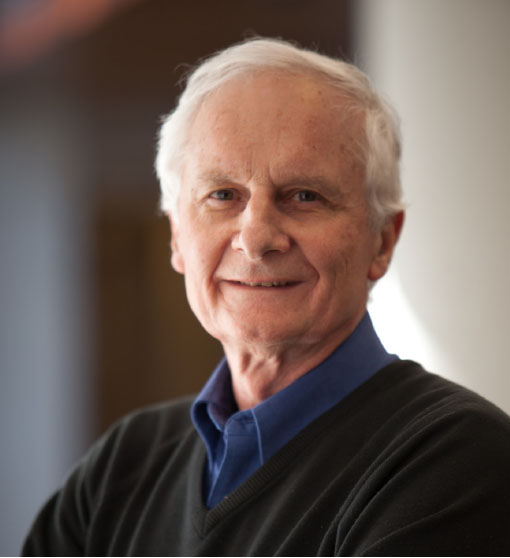

Dedicated to Preventing Cervical Cancer

Dedicated to Preventing Cervical CancerJessica Kahn, M.D., M.P.H., discusses her new role in helping to shape the future of clinical and translational research at Einstein

-

Paying the Einstein Experience Forward

Paying the Einstein Experience ForwardAlumni donors Jill Zimmerman, M.D. ’93, and Michael Stifelman, M.D. ’93 on why they are giving back to Einstein

-

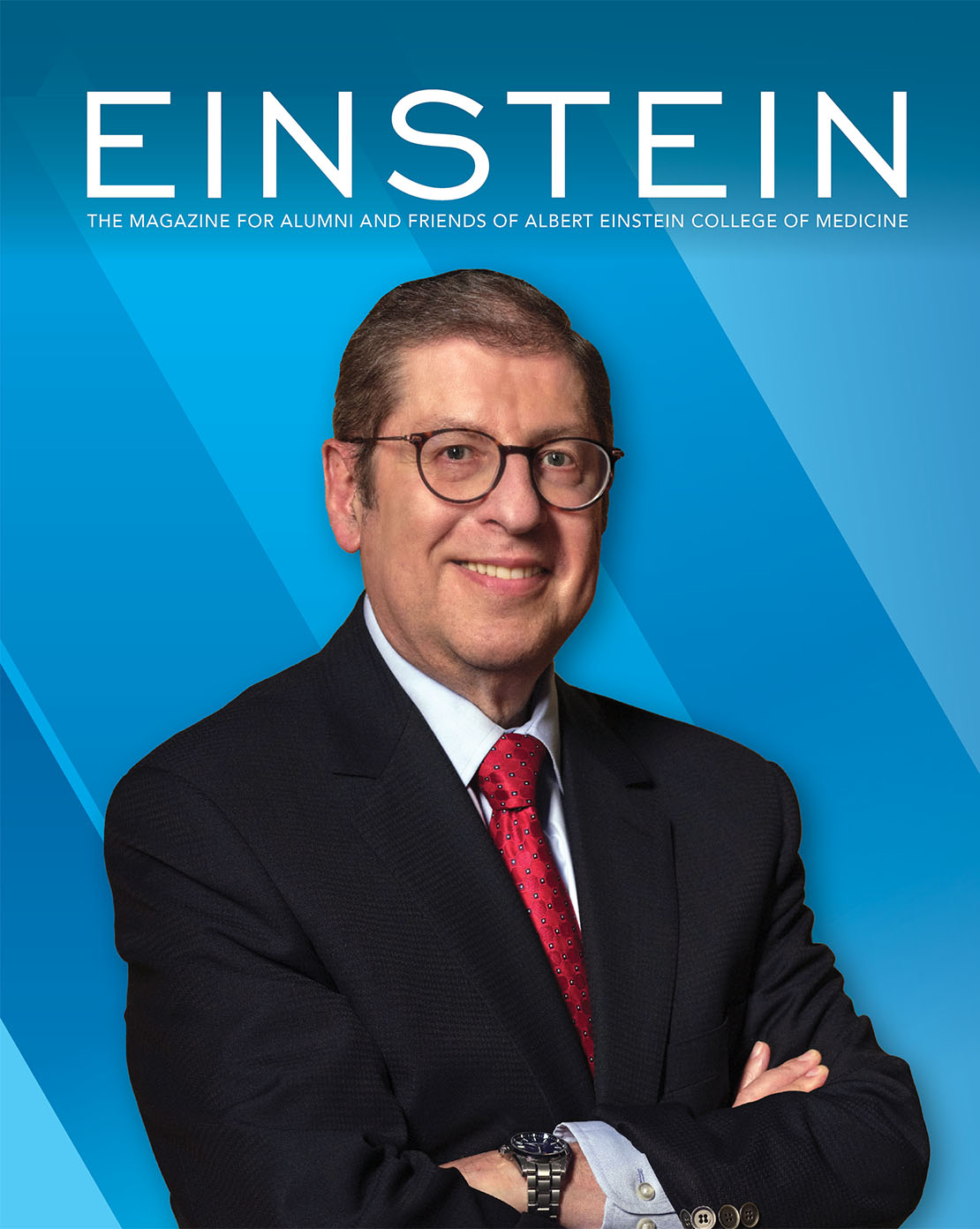

Message From the Dean

Message From the DeanYaron Tomer, M.D., updates alumni, friends, faculty, staff, and students on recent achievements at Einstein

-

Message From the Board Chair

Message From the Board ChairRuth L. Gottesman, Ed.D., shares news about programs and facilities made possible thanks to philanthropic support

-

Families Welcomed at Inaugural Open House

Families Welcomed at Inaugural Open HouseParticipants connected with leadership, faculty, and alumni at the daylong event geared to parents and relatives

-

Einstein Celebrates Opening of Anatomy Lab

Einstein Celebrates Opening of Anatomy LabAn August ribbon-cutting ceremony marked the launch of the state-of-the-art facility, named in honor of Einstein’s second dean

-

Class of 1975 Celebrates 50th Reunion

Class of 1975 Celebrates 50th ReunionClassmates gathered at the Manhattan Penthouse to mark their milestone anniversary and support their alma mater

-

Marilyn and Stanley M. Katz Patio Unveiled

Marilyn and Stanley M. Katz Patio UnveiledAn 1,800-square-foot space outside the lower level of Albert’s Den has been transformed into an inviting relaxation and study spot

-

Women’s Division Hosts Spirit of Achievement

Women’s Division Hosts Spirit of AchievementFour women were recognized for their vision, leadership, and contributions at the Rainbow Room in New York City

-

Giving Thanks at the Dean’s Society Reception

Giving Thanks at the Dean’s Society ReceptionEinstein Trustee Sarah Schlesinger Hirschfeld, M.D., hosted the event, held at the New York Historical in September

-

Scientific Salon Showcases Einstein Research

Scientific Salon Showcases Einstein ResearchEinstein trustees, alumni, donors, and friends learned more about the College of Medicine’s latest work

-

Einstein Names Endowed Chairs, Faculty Scholars

Einstein Names Endowed Chairs, Faculty ScholarsEinstein’s Board of Trustees recognizes outstanding contributions in epidemiology & population health, and more

By giving to Einstein, you advance the future of medical education, innovation, and discovery. Find a program to support today.

Make a Gift