-

-

ECHO Anniversary: In the Room Where it Happened

ECHO Anniversary: In the Room Where it HappenedAs ECHO marks 25 years, Einstein alumni recall the earliest days of the free clinic, which became a national model

-

Learning From People With Disabilities Through Service

Learning From People With Disabilities Through ServiceEinstein medical students partner with a Bronx running group, the Amputee Walking School, and Montefiore Adaptive Sports teams

-

$100M Gift Strengthens Biomedical Research and Training at Einstein

$100M Gift Strengthens Biomedical Research and Training at EinsteinAn anonymous contribution to the College of Medicine, announced in 2023, has already begun to transform biomedical investigations and educational programs

-

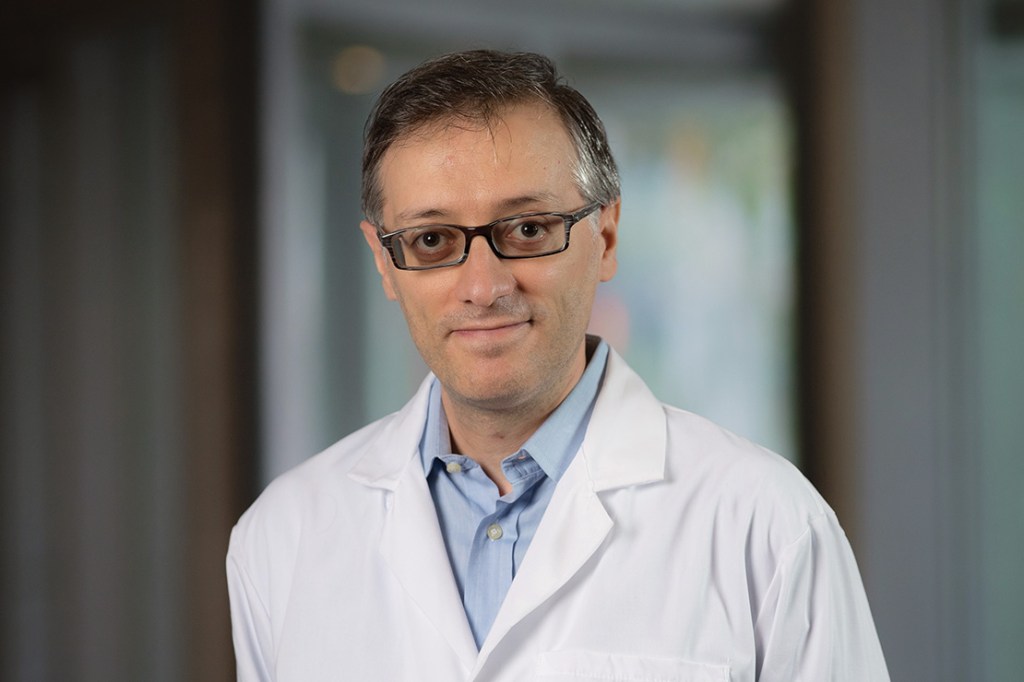

A Conversation With Cardiac Scientist Gaetano Santulli

A Conversation With Cardiac Scientist Gaetano SantulliAssociate professor of medicine and of molecular pharmacology

-

Lab Chat With Cancer Researcher Rebeca San Martin

Lab Chat With Cancer Researcher Rebeca San MartinAssistant professor of oncology and of cell biology

-

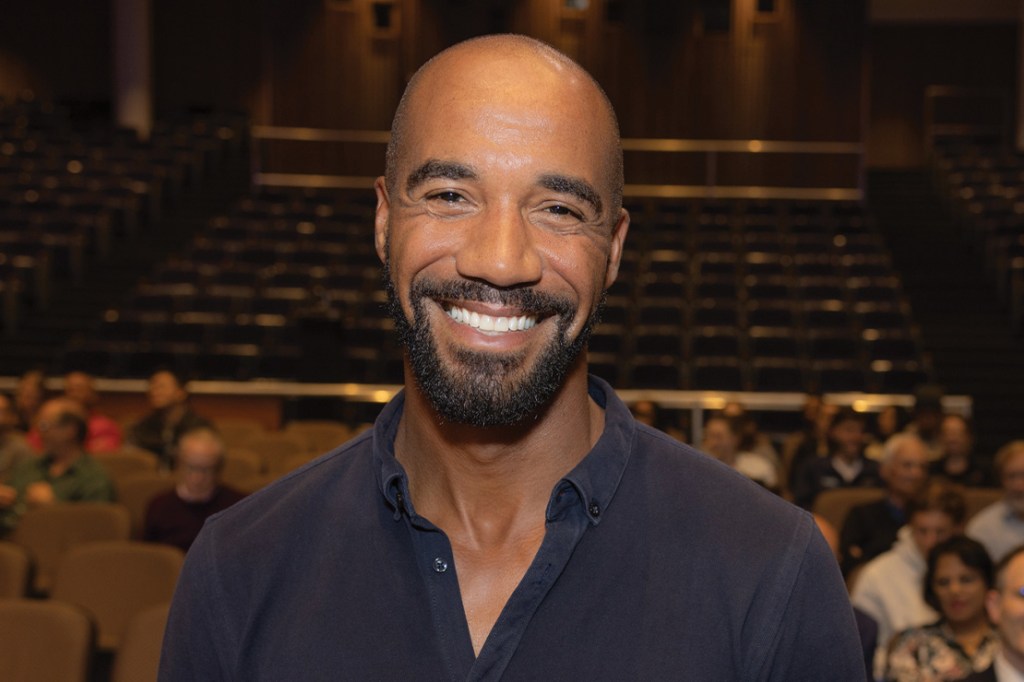

An Interview With Einstein Trustee George O’Garro

An Interview With Einstein Trustee George O’GarroOur newest Trustee discusses why he’s such a strong advocate for Einstein

-

A Shared Lifetime of Giving Back to Einstein

A Shared Lifetime of Giving Back to EinsteinMarilyn and Stanley M. Katz, both Bronx natives, have been devoted and prolific supporters of the College of Medicine for decades

-

Building a Bridge From Nursing to Medical School

Building a Bridge From Nursing to Medical SchoolA legacy of service inspires an Einstein alumnus, Scott Suchin, M.D. ’99, R.N., to create a unique scholarship

-

Spirit of Achievement Marks 70th Anniversary

Spirit of Achievement Marks 70th AnniversaryEinstein Women’s Division hosted more than 250 supporters at the annual awards ceremony, raising a record-setting amount for research

-

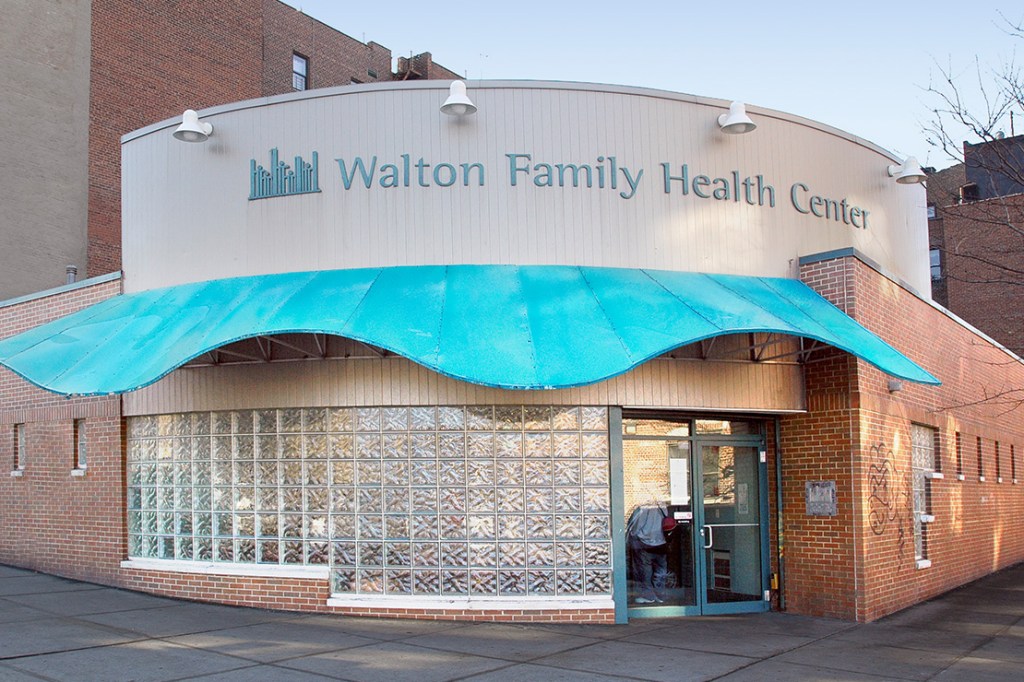

General Internal Medicine Marks 20 Years of Service to the Bronx

General Internal Medicine Marks 20 Years of Service to the BronxThe division within the department of medicine was created in 2004 and has grown into a thriving hub for clinical care, research, and education, with 75 full-time faculty and more than 50 staff members

-

Message From the Board Chair

Message From the Board ChairRuth L. Gottesman, Ed.D., provides an update on philanthropy, trustee news, and more

-

Message From the Dean

Message From the DeanYaron Tomer, M.D., updates alumni, friends, faculty, and staff on achievements at Einstein

-

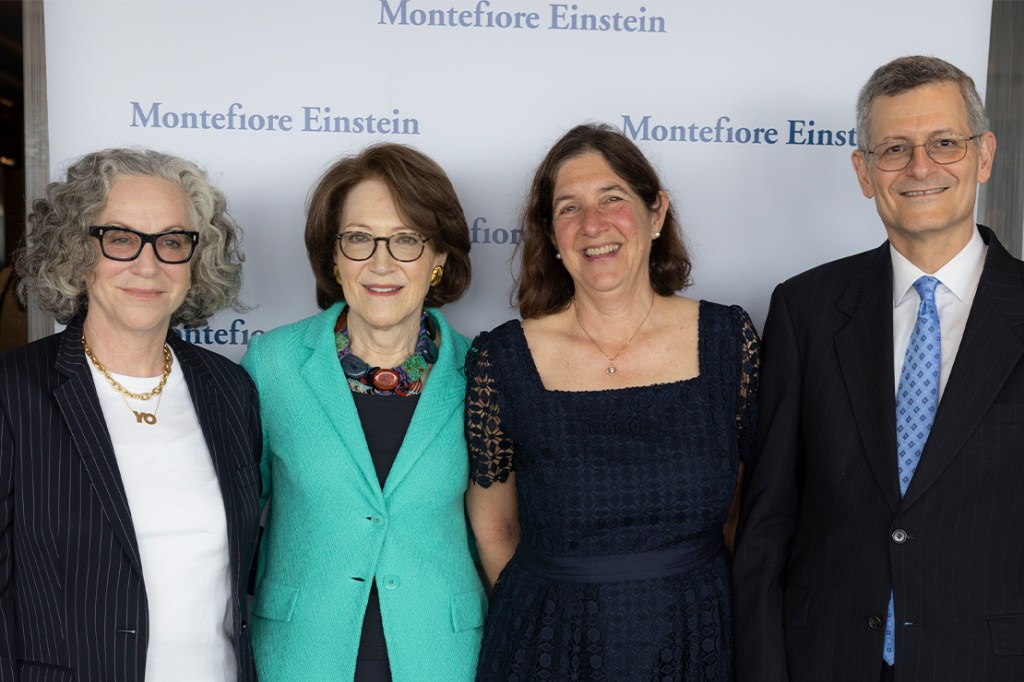

Paying It Forward at the Dean’s Society Reception

Paying It Forward at the Dean’s Society ReceptionThe annual event celebrates alumni, parents, and friends for their leadership gifts

-

‘Cards for a Cause’ Supports Weight Research

‘Cards for a Cause’ Supports Weight ResearchThe event showcased Einstein research, boutique fashion, lunch, and card games

-

Raising a Glass—and Funds—for Cancer

Raising a Glass—and Funds—for CancerThe event’s proceeds support cancer research at Montefiore Einstein

-

Reunion Dinner Dance and Alumni Day

Reunion Dinner Dance and Alumni DayMore than 200 alumni came together to reconnect and celebrate Einstein

-

Class Notes: Fall/Winter 2024

Class Notes: Fall/Winter 2024Updates from graduates across the decades, from the 1960s to the 2020s

-

In Memoriam: Fall/Winter 2024

In Memoriam: Fall/Winter 2024Recently deceased members of the Einstein and Montefiore communities

-

Legacy Society: Samuel Silverstein, M.D. ‘63

Legacy Society: Samuel Silverstein, M.D. ‘63The Legacy Society recognizes individuals who choose to advance Einstein’s mission through gifts in their estate plans

By giving to Einstein, you advance the future of medical education, innovation, and discovery. Find a program to support today.

Make a Gift