He recounts a second story, about an encounter later that terrible day, when a young woman in hospital scrubs came rollerblading over to the triage unit and asked for the physician in charge.

“‘I’m Doctor So-and-So, a veterinarian, and I’m here to help,’” Dr. Prezant recalls her saying. “I replied something like, ‘We’ve been attacked and I don’t know how many thousands are dead and injured. This is not a time to worry about cats and parakeets!’ She gave me a look that I soon found out I deserved and replied, ‘Listen up—by federal statute all rescue dogs must stop working after four hours unless a veterinarian is present. So you need to get me to the rescue dogs or I’m shutting them down.’”

It was a humbling—and eye-opening—moment, he says. “Due to pure ignorance, I almost wound up shutting the site down,” he says. “Later it occurred to me, ‘The dogs had to be monitored every four hours, but we let human beings work at the disaster site for God knows how many hours.’ Something to remember.”

I have no hobbies. I like working. My goal is to die at work. Seriously.

— Dr. David Prezant

Dr. Prezant, professor of medicine and of epidemiology & population health at Einstein and a pulmonologist at Montefiore, grew up two blocks away from the Moses campus of Montefiore, the child of an elementary school teacher (his mother) and a high school teacher and administrator (his father).

Science came naturally to their son, and after college at Columbia University he intended to pursue a Ph.D. in biochemistry, with designs on a career in bench research. Yet he couldn’t shake the feeling that his talents were better suited to medicine. He enrolled at Einstein in 1977, less than confident about his decision.

“For the first two years, I wasn’t a very motivated student—average at best,” he admits. But in his third-year clinical rounds, he found an affinity for pulmonary medicine and intensive care.

“The ICU [intensive care unit] is very much like working in a lab, with lots of data to process, plus the challenge of caring for patients and interacting with their families—complete strangers with whom you form this incredible bond and who are forever scarred if the ICU experience doesn’t go well,” Dr. Prezant says. “The responsibility is immense. It was then I began to realize how engaging it could be to care for patients, and how much of a privilege it is.”

After Einstein, he began a residency in internal medicine at Harlem Hospital, preferring to work with underserved populations as he’d done in the Bronx. Dr. Prezant returned to the Bronx for fellowships in pulmonary care and pulmonary research in a joint program at Montefiore and Jacobi hospitals. All the while he moonlighted at Harlem Hospital, regularly working six or seven days a week—a schedule he still keeps. “I’m the most boring person on Earth,” he insists. “Other than going to the gym, I have no hobbies. I like working. My goal is to die at work. Seriously.”

In the mid-’80s, Dr. Prezant joined the Einstein and Montefiore staffs in a role that combined clinical research and patient care. With a new wife and two stepchildren to help support, he also applied for a part-time position with the FDNY. He seemed a shoo-in for a newly opened pulmonologist position, only to be told by the then-fire commissioner that physicians with military experience were preferred. Walking out of the commissioner’s office, he tried one last gambit, mentioning that he’d been a Boy Scout. “And the commissioner goes, ‘Well, that involves a uniform. Great—you’re hired!’” Dr. Prezant recalls.

Over the years, Dr. Prezant became more and more involved with the FDNY’s first responders, made up of EMS providers (paramedics and emergency medical technicians) as well as firefighters. That meant treating first responders in the field and in the hospital, evaluating new firefighting gear and personal protective equipment, developing new health initiatives—and gradually winning the trust of the rank and file.

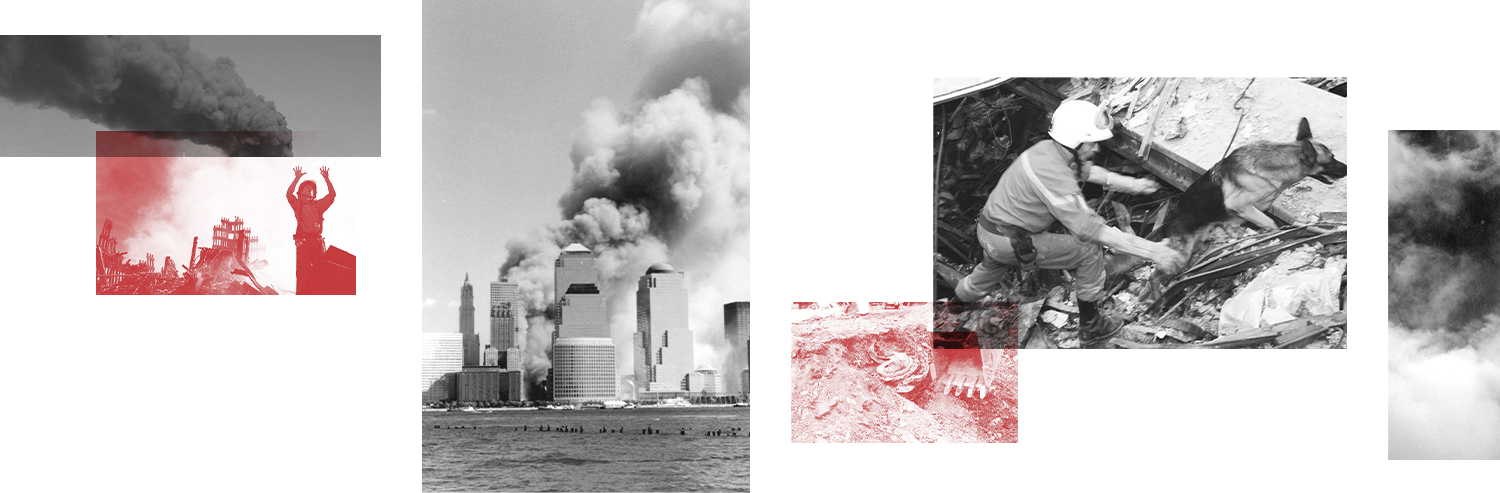

By 1996, Dr. Prezant had hit his stride: He was appointed deputy chief medical officer at the FDNY, was placed in charge of the pulmonary clinic at Montefiore and, at Einstein, took over the second-year course called Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Disaster Medicine, which is now in its 25th year. His professional life was full and relatively uneventful. And then came 9/11.

As time went on, first responders experienced an increasing number of serious WTC-related health problems.

Dr. Prezant escaped Ground Zero with cuts and bruises and a sore back, and quickly returned to work. His one lingering complaint was a case of “World Trade Center cough syndrome,” an all-too-common legacy of the noxious mix of asbestos, burning plastics, jet fuel, and other toxins that fouled the air around lower Manhattan for weeks on end. He fully recovered after a few months, but many others didn’t, as he would eventually document.

Following the attacks, Dr. Prezant and his team—including staffers at the FDNY and at Einstein, Montefiore, and other medical centers—launched the Fire Department’s WTC Medical Monitoring and Treatment Program under a multimillion-dollar grant from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (See “Teaming Up to Study First Responders,” below.)

“We expected an increase in upper and lower pulmonary disease and other health problems,” he says. “But to this day, I am amazed at the magnitude of those issues.”

In a 2006 paper in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine—one of the first of more than 100 attack-related papers in his curriculum vitae—he reported that 9/11 first responders lost substantial lung function in the year following the attacks; they suffered more than 12 times the decline expected with normal aging.

The largest lung-function decline occurred in workers who arrived at the WTC site the morning of 9/11, when the dust cloud was most intense. Before 9/11, the FDNY had expanded its annual medical exams to include lung-function tests and other critical health measures—a move championed by Dr. Prezant and one that provided crucial clinical baselines for the WTC studies and gave them added weight.

Dr. Prezant and his team described findings that were even more disturbing in a 2010 New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) paper. A significant portion of FDNY rescue workers who’d experienced acute lung damage still had not recovered normal lung function a full seven years after 9/11. For 13% of the firefighters and 22% of the EMS providers, lung function was below normal for their ages.

Previous studies of firefighters had found that the lung-function impairments caused by inhaled pollutants were mild and reversible. The serious lung damage inflicted on 9/11 rescue workers, the 2010 study concluded, most likely stemmed from repeated daily exposure to high concentrations of airborne particles and gaseous chemicals.

The NEJM study was remarkable for its findings and for its size and scope. It remains the largest longitudinal study of occupational influences on lung function ever reported. The researchers performed 62,000 spirometry (lung-function) tests on nearly 13,000 first responders, or 92% of those present at the WTC site during the first two weeks after the attacks—a testament to the trust that firefighters and EMS providers had placed in Dr. Prezant and the WTC Medical Monitoring and Treatment Program at FDNY’s Bureau of Health Services.

“Many people affected by the attacks suspected that researchers were the enemy—that we were just trying to prove that WTC dust had no lasting health impacts,” Dr. Prezant says. “But that wasn’t the case within the FDNY, where they realized we were partners, that we would call it the way it is.”

As time went on, first responders experienced an increasing number of serious WTC-related health problems.

In 2010, Dr. Prezant found that first-responding firefighters had elevated rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). More than 10% of them had signs of PTSD four years after the WTC attack, creating significant difficulties at work and at home, he reported in Public Health Reports.

A 2011 study in The Lancet reported that firefighters exposed to the WTC site were at least 19% more likely than their nonexposed colleagues to develop cancer in the seven years following the disaster. “We expected we might see an increase in cancers after 20 years, but not after just seven,” he says.

David’s lobbying skills are legendary and were seminal in landing the Zadroga Act.

— Dr. Simon D. Spivack

The results, Dr. Prezant said at the time, “support the need to continue monitoring firefighters and others who responded to the World Trade Center disaster or participated in recovery and cleanup at the site. This monitoring should include cancer screening and efforts to prevent cancer from developing in exposed individuals.”

As he had recommended, the federal WTC Health Program (the new name for the WTC Medical Monitoring and Treatment Program following passage of the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act in 2011) was expanded in 2012 to include cancer screening and prevention efforts.

In 2016, the team reported in Mayo Clinic Proceedings that autoimmune diseases had also increased. First responders were 34% more likely to suffer from diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, and psoriatic arthritis than a comparison group of Midwestern men.

In 2018, Dr. Prezant and colleagues published a study in JAMA Oncology, reporting their findings that firefighters faced an increased risk for developing myeloma precursor disease, which in some people leads to the blood cancer multiple myeloma.

A 2019 paper in JAMA Network Open linked WTC exposure to an increase in heart disease among the first responders. Those who arrived first at the site had a 44% higher risk of cardiovascular complications than those who arrived later in the day. Similarly, those who worked at the WTC site for six months or longer were 30% more likely to have experienced a primary or secondary cardiovascular event than those who worked less time at the site.

“An important message is that new chest pain in this group should not automatically be attributed to well-known WTC-related illnesses, such as acid reflux or obstructive airway disease. It might very well be associated with CVD [cardiovascular disease},” Dr. Prezant said at the time.

Dr. Prezant has had many collaborators, including:

The late Thomas Aldrich, M.D., professor of medicine and director of the Pulmonary/Critical Care Training Program at Montefiore and Einstein and of the Pulmonary Function Laboratory at Montefiore

David W. Appel, M.D., associate professor of medicine and director of the Pulmonary Sleep Center at Montefiore

Krystal Cleven, M.D., assistant professor of medicine and a pulmonologist at Montefiore

Hillel Cohen, Dr.P.H., M.P.H., professor of epidemiology & population health at Einstein

Charles Hall, Ph.D., professor of epidemiology & population health and in the Saul R. Korey Department of Neurology at Einstein

Simon D. Spivack, M.D., M.P.H., professor of medicine, of epidemiology & population health, and of genetics at Einstein and a pulmonologist at Montefiore

Amit Verma, M.B.B.S., professor of medicine and of developmental and molecular biology at Einstein and director of hemato-oncology at Montefiore

Mayris Webber, Dr.P.H., professor of epidemiology & population health at Einstein

Rachel Zeig-Owens, Dr.P.H., research assistant professor of epidemiology & population health at Einstein

Before 9/11 and especially afterward, Dr. Prezant saw that his role as an FDNY physician stretched beyond medical care into policy and politics—a challenge he approached with a blend of empathy and science.

“I’m especially proud of our transition from compassion-driven advocacy to data-driven advocacy,” he says. “The idea was that knowing what went on down there on 9/11 would result in the right treatment for our responders and would enable us to advocate better for government support. Eventually all that came true, but not without a struggle. And while we now have cancer covered, we are still working on getting certain autoimmune diseases covered under the federal WTC Health Program.”

As early as 2002, Dr. Prezant began lobbying members of Congress for money to care for 9/11 first responders.

“During those first trips to the Hill, naysayers in the hearing rooms would tell us, ‘Oh, they have symptoms and our hearts go out to them, but most people with symptoms will get over it,’” Dr. Prezant says. “But starting in 2006, after we had strong objective evidence, no one doubted that the first responders were actually suffering. Then the legislators switched to saying, ‘We don’t know how we’re going to pay for this. We don’t know if it’s a priority.’”

In 2008, Dr. Prezant testified before the U.S. House of Representatives’ Appropriations Committee on behalf of what is now called the WTC Health Program. After listing the many health issues plaguing the first responders, he told the representatives that a commitment to long-term funding was needed “to ensure that we can continue necessary treatment, monitoring, and research into the future. As we know in environmental-occupational medicine, there is often a significant lag time between exposure and emerging diseases. … The actual effect of the dust and debris that rained down on our workforce on 9/11 may not be evident for years to come.”

He testified again in 2010, this time in support of the proposed Zadroga Act, which would provide more funding for health monitoring and financial aid for the first responders, volunteers, and survivors of the attacks.

“These healthcare findings—they really don’t speak to the heart of the matter, to what our patients are suffering on a daily basis,” he told the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions. He went on to describe one such sufferer:

“On 9/11, when the Twin Towers were burning, FDNY firefighters ran into those buildings. By the time the second plane hit, most realized that this was not going to be just a fire; this was an attack. And yet they continued to run in. I have a patient who told a younger firefighter, ‘You go left, I’ll go right.’ That younger firefighter died. And that older firefighter, because of that decision, feels he was responsible for that firefighter’s death. He woke up every night screaming for the first six months. And now he wakes up screaming less, but still so often that his wife sleeps in a separate room. That’s not the way things should be.”

Soon after, comedian Jon Stewart dedicated an entire episode of The Daily Show to the Zadroga Act, more or less shaming Congress into passing the proposal, which President Barack Obama signed into law in January 2011. Four years later, the act was reauthorized and extended through 2090—essentially providing lifelong care for health-impaired first responders. Mr. Stewart got much of the credit, but it could be said that Dr. Prezant and other scientists softened up the hardened lawmakers for the comedian’s final punch.

“David’s lobbying skills are legendary and were seminal in landing the Zadroga Act,” says Simon D. Spivack, M.D., M.P.H., professor of medicine, of epidemiology & population health, and of genetics at Einstein and a pulmonologist at Montefiore. “He has been a model of highly effective and caring medicine, science, and advocacy—a very challenging juggling act. We are truly fortunate to have him as part of the Einstein community.”

Dr. Prezant “has always been a tireless advocate for the health and safety of every FDNY member,” says Fire Commissioner Daniel A. Nigro. “Through his work with the WTC Health Program, he has honored the memory of all those innocent lives taken on Sept. 11 and fought for the health of FDNY members—and really, every first responder—who bravely served in the rescue and recovery effort at the World Trade Center. His work has been key to ensuring early intervention for our members battling illness and in proving that funding is needed to care for the men and women who sacrificed so much to protect our city.”

In 2010, Dr. Prezant was appointed the FDNY’s chief medical officer and special adviser to the fire commissioner on health policy. He is responsible for the WTC Health Program at the FDNY, its Bureau of Health Services, and its Office of Medical Affairs. His 9/11 studies earned him the American Thoracic Society’s Public Service Award (2011) and the American College of Chest Physicians’ Presidential Honor (2012).

Apart from his 9/11 studies, Dr. Prezant has played major roles in the FDNY’s responses to Hurricane Sandy, the Ebola virus, and, most recently, COVID-19.

“Dr. Prezant has been an essential member of my team during the pandemic,” Fire Commissioner Nigro says. “He has provided daily, and even hourly, updates to ensure our members were always armed with the latest information and operating with the highest level of personal protective equipment.”

In his teaching role at Einstein, Dr. Prezant over the years has mentored almost three dozen epidemiologists, biostatisticians, and pulmonary fellows in his lab. And for one month each year, he supervises the training of young doctors in pulmonary and critical care medicine at Montefiore.

“When I joined Dr. Prezant’s research team in 2008 as a newly minted epidemiologist, I knew I could make a difference under his leadership,” says Rachel Zeig-Owens, Dr.P.H., research assistant professor of epidemiology & population health at Einstein, director of epidemiological research at the FDNY’s WTC Health Program, and a co-author on many of Dr. Prezant’s papers. “But I didn’t know that 13 years later I’d still be at it with a colleague who truly cares about his patients, his collaborators, and the research as a whole.”

Dr. Prezant still cares for patients. “That’s what I live for,” he says. “Being a physician is, without a doubt, the greatest job on the planet.”