Xueting “Hattie” Zhang, a second-year medical student at Einstein, was intrigued but nervous. She was looking for a way to help out during the pandemic, and an email announcing a new summer educational offering had just popped up on her computer screen. Called the “COVID-19 Design Challenge,” it asked students to devise innovative solutions for making healthcare workers and the public safer in a future wave of COVID-19 or another infectious disease. And it gave them just eight weeks to do it.

If motivated, interested, and excited students get together to work on a challenge from different vantage points, good things will happen.

— Dr. Todd Cassese

“I wanted to register for it, but I was worried that if my design required engineering, I wouldn’t have the skill that was needed,” she says. Then she learned that participants would work in multidisciplinary groups that included engineering students from the City University of New York (CUNY). So she took a deep breath and signed up—along with 16 others from Einstein, including medical students and Ph.D. candidates, all eager to help fight a virus that was ravaging the Bronx.

“If motivated, interested, and excited students get together to work on a challenge from different vantage points, good things will happen,” says Todd Cassese, M.D., associate dean for medical education, an associate professor of medicine at Einstein, and a hospitalist at Montefiore. “These types of experiences can be transformational.”

The idea to create a design challenge arose from conversations between Dr. Cassese and Joshua Nosanchuk, M.D., senior associate dean for medical education at Einstein and an infectious-diseases clinician at Montefiore, about how designs for personal protective equipment (PPE) for healthcare workers hadn’t progressed much over the years. “This moment seemed like an opportunity to reframe what’s really important during an outbreak—not just PPE, but all the challenges we were facing—and get some really bright minds to think about it,” Dr. Cassese says.

While Einstein students had the medical know-how, Dr. Cassese realized that engineering expertise would also be needed. Since Einstein already had a relationship with CUNY with existing master’s of public health and Centers for AIDS Research programs, it seemed like a good place to start.

Dr. Cassese pitched the idea of a design challenge to the dean of the Grove School of Engineering at the City College of New York/CUNY, where Sabriya Stukes, Ph.D., caught wind of it. Dr. Stukes, who earned her doctoral degree in microbiology and immunology at Einstein in 2014, is the associate director of CUNY’s master’s in translational medicine (MTM) program.

“MTM blends engineering, science, and business concepts to teach scientists and engineers how to design and commercialize medical technologies,” Dr. Stukes explains. “So it felt like a very good fit.” Dr. Stukes and Jeffrey Garanich, Ph.D., director of MTM, discussed ways in which CUNY engineering faculty and students could participate.

Faculty members from Einstein and CUNY then divided students into 10 teams, with most containing a mix of engineering and medical students. Each team’s goal was to identify an unmet public health need and come up with a possible solution. There was also an incentive: Winning teams would be invited to submit a budget to develop and refine their concepts and could be awarded up to $5,000, paid from an Einstein educational fund for curriculum innovations.

Initially, many medical students worried about their technical skills, while the engineers felt they lacked medical training. “The light-bulb moment was when they realized that wasn’t a weakness,” Dr. Stukes says. “They found they could work across disciplines and admit, ‘I don’t know about this, but here’s what I do know, and I am willing to learn.’”

CUNY engineering faculty developed a curriculum that taught students how to sift through possible solutions, develop prototypes, make an initial proposal, build a business case, and craft a compelling narrative about their technology.

Einstein brought in experts with medical backgrounds, including pulmonologists, who explained how ventilators work, and microbiologists and infectious-disease experts, who covered molecular virology. “There’s no way this would have happened without the generous donation of time and energy from a series of experts in engineering, entrepreneurship, design, science, and medicine,” Dr. Cassese says.

Ms. Zhang’s team included fellow second-year Einstein medical student Kevin Batti and three CUNY engineering students. The challenge they chose was reducing healthcare workers’ risk of exposure to the coronavirus when putting on, taking off, or storing their PPE.

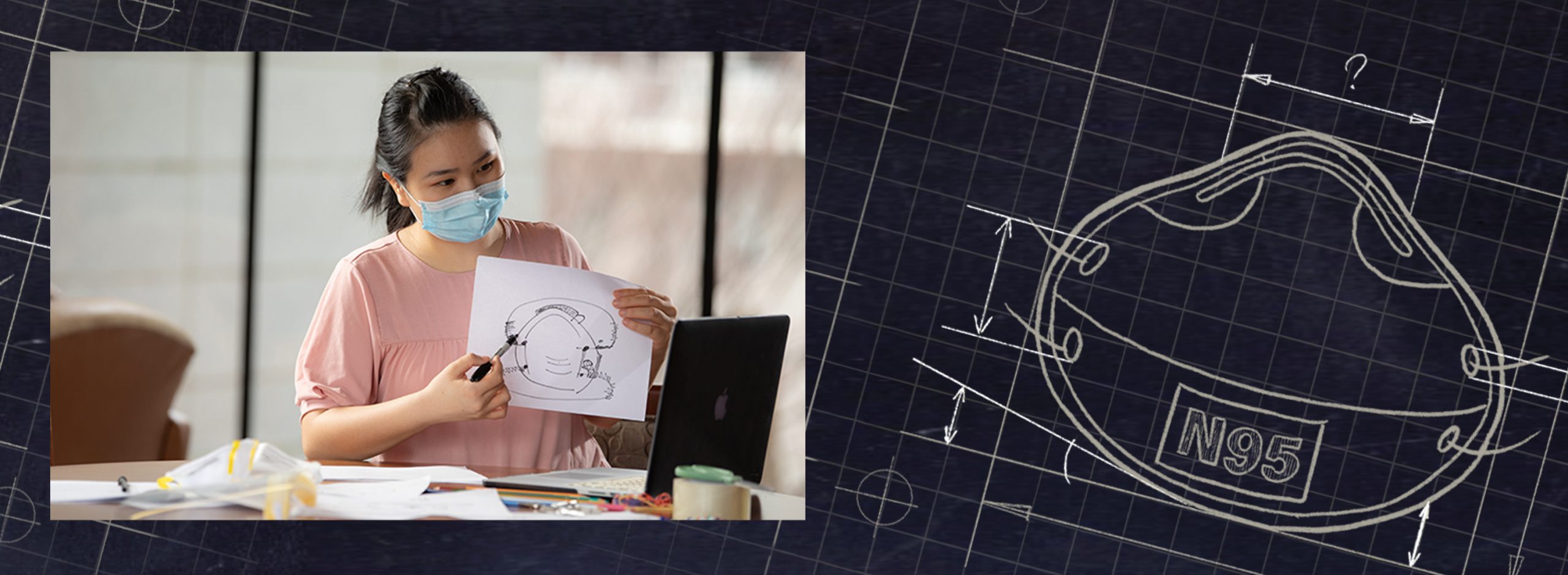

The pandemic required the team members to discuss their concepts on videoconference calls. “It was definitely tricky, not being able to pass around tangible objects such as masks,” Mr. Batti says. “We’d hold drawings up to the camera and point.”

At the first meeting, Ms. Zhang came up with what she recalls as “a very rough idea”: a device for allowing people to efficiently and safely put on and take off face masks while minimizing the risk of contamination. One of the engineering students then sketched a design on paper.

The team kept returning to Ms. Zhang’s concept for several weeks—only to abandon it in favor of devising something more impressive. “But when it came to implementing our design, we decided that simplicity was our best friend,” Mr. Batti says. The team soon crafted a working prototype from inexpensive parts ordered from Amazon.

“We were excited to arrive at something we felt could actually scale and go to market,” Mr. Batti says.

When the eight-week challenge was up, each group presented its project to a panel of five experts. The judges from Einstein were Peter Bernacki, senior director of business services, and Helen Rhim, M.D., M.P.H., director of educational innovations in the office of medical education and the fellowship director for pediatric hospital medicine at Children’s Hospital at Montefiore.

Other judges were Lola Brown, Ph.D., assistant dean for research at Weill Cornell Medicine; Aaron Kyle, Ph.D., a senior lecturer in biomedical engineering design at Columbia University; and Lawrence Levy, former chief financial officer of Pixar Animation Studios.

“I was so impressed by the creativity and the breadth of products—from things people could use in daily life to specific medical equipment to help protect frontline workers,” Dr. Rhim says. “The high quality of the projects made it difficult to decide on the finalists.”

While proud of their design, Ms. Zhang and Mr. Batti didn’t expect to be among the finalists. “I didn’t think we would win because everyone in the competition was really impressive—talented and smart,” Mr. Batti says. “We were going up against some amazing stuff like new types of ventilators.” Much to their surprise, their face-mask device earned the top score among the four groups chosen as finalists.

“An important takeaway for the students is that sometimes the simplest ideas are best,” Dr. Stukes says.

Other winning ideas included two safer ways for healthcare workers to deliver oxygen to patients and a method for disinfecting taxis and car services to reduce virus transmission. Members of the winning teams are using the money given to them to revise their prototypes and file patent applications.

Teamwork is so crucial to being a healthcare provider. … We can teach our students facts, but we need them to be able to apply them at the bedside and in innovative research.

— Dr. Helen Rhim

Ultimately, the first-ever design challenge also exceeded the expectations of those who had created it. “The degree of innovation really surprised me,” Dr. Cassese says. But he says the primary goal of the course was to enrich students’ educational experiences. “We think about how we can give learners the tools and confidence to pursue ways to improve our healthcare system and to help their patient community, to really make a difference,” he says. “By that measure, the design challenge was an incredible success.”

Dr. Rhim wholeheartedly agrees. “Teamwork is so crucial to being a healthcare provider,” she says. “That application phase is so important to what we are trying to achieve in the medical school curriculum. We can teach our students facts, but we need them to be able to apply them at the bedside and in innovative research.”

Ms. Zhang, who wants to specialize in internal medicine, says that she’s excited about tackling more problems. “This experience showed me that I don’t have to be an engineer or a coder to be an innovator. I can do it with everyday projects, and I can find a great group of people to help perfect my idea.”

Mr. Batti, who hopes to become an orthopedic surgeon, agrees. “Realizing you can take an idea from a vision to a tangible product is really cool,” he says. “I feel like I can go on to improve operations in the future.”