-

-

Vern Schramm: Pursuing the Ones That Got Away

Vern Schramm: Pursuing the Ones That Got AwayA cancer therapy designed by Dr. Schramm saves 10 percent of patients who receive it. Now he is working on a cure for the rest

-

New Data Science Institute Takes Shape at Einstein

New Data Science Institute Takes Shape at EinsteinA $7M gift will help Einstein researchers harness large sets of data that can lead to medical breakthroughs

-

Practice Makes Perfect: Improving Health in the Bronx

Practice Makes Perfect: Improving Health in the BronxEinstein researchers are partnering with primary-care providers in the Bronx to learn what works best for patients who have asthma, diabetes, dementia, and other conditions

-

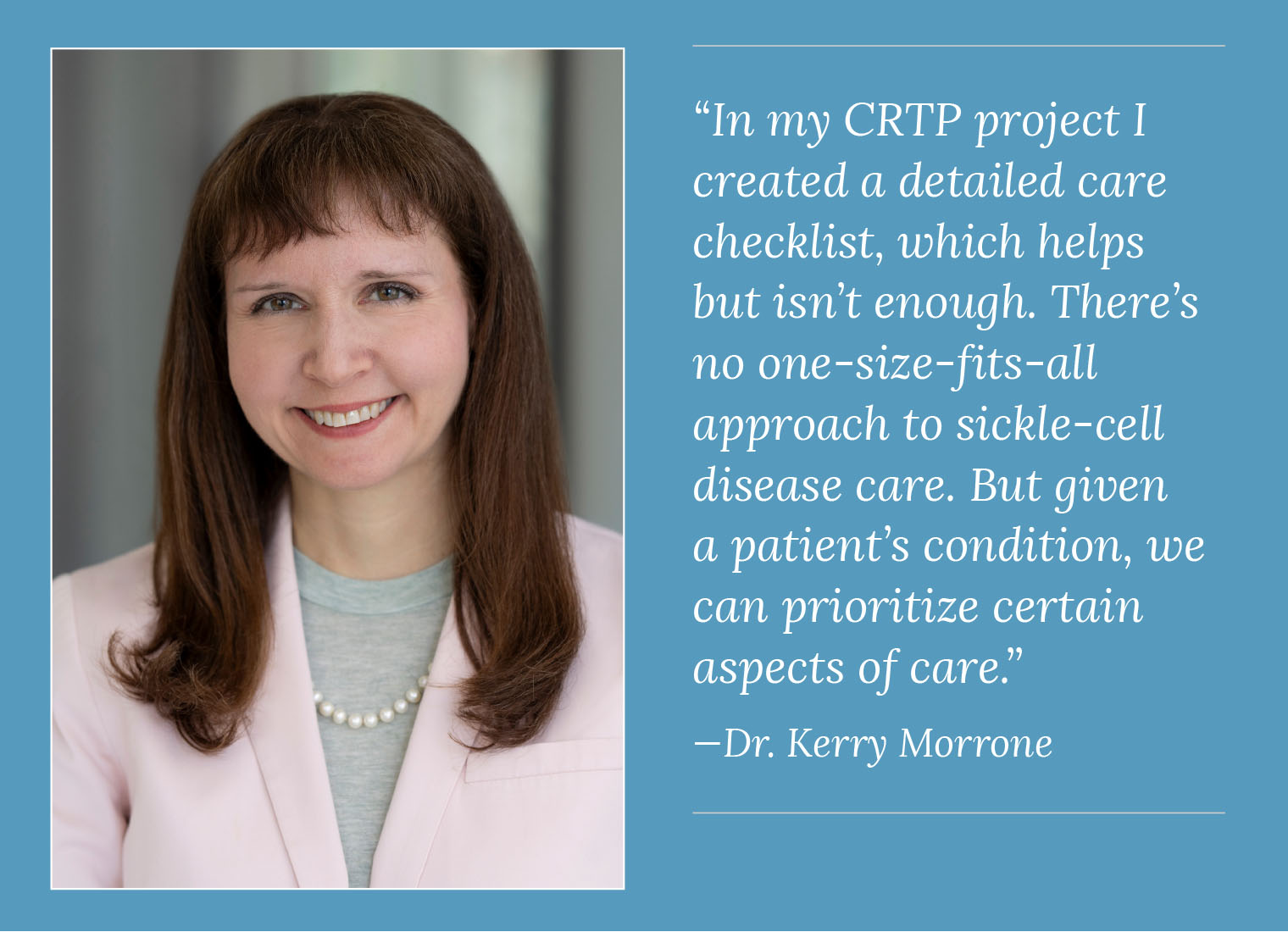

Alumni Win K Grants to Pursue Crucial Medical Research

Alumni Win K Grants to Pursue Crucial Medical ResearchThe Einstein scientists are working on COVID-19 vaccines and therapies, sickle-cell disease, and HIV-related cardiovascular disease

-

A Chat With the OB/GYN and Women’s Health Chair

A Chat With the OB/GYN and Women’s Health ChairMark Einstein, M.D., discusses gynecologic oncology, cervical cancer prevention, and his return to Einstein

-

Outmatching the Scholarship Match

Outmatching the Scholarship MatchEinstein alumni and friends have taken part in a first-of-its-kind one-to-one match program and endowed dozens of need-based scholarships to pay medical students’ living expenses

-

Membership in Albert Einstein Legacy Society Doubles

Membership in Albert Einstein Legacy Society DoublesEinstein alumni, faculty, parents, and friends are securing the College of Medicine’s future through legacy gifts in their estate plans

-

Legacy Society: Ellen Marmur, M.D. ’99, and Jonathan Marmur, M.D.

Legacy Society: Ellen Marmur, M.D. ’99, and Jonathan Marmur, M.D. -

Einstein Board Welcomes Three New Members

Einstein Board Welcomes Three New MembersNew Trustees are James M. Butler, Stuart Spodek, and Michael Stern; Betty Feinberg honored for her years of service

-

Einstein in Your Neighborhood: 2025

Einstein in Your Neighborhood: 2025The Einstein Alumni Association shares updates with alumni in California, Florida, and New Jersey

-

Palm Beach Event Explores Research on Aging

Palm Beach Event Explores Research on AgingLong-standing supporters Marilyn and Stanley Katz honored for their role in advancing Einstein’s mission

-

Einstein Appoints Endowed Chairs, Faculty Scholar

Einstein Appoints Endowed Chairs, Faculty ScholarEinstein’s Board of Trustees recognizes outstanding contributions in neuroscience, oncology, and more

-

Tenure for Five Einstein Professors

Tenure for Five Einstein ProfessorsThe Einstein Board of Trustees, along with Yaron Tomer, M.D., recently awarded tenure to these faculty members

-

Eight Honored at 2025 Alumni Awards

Eight Honored at 2025 Alumni AwardsDistinguished graduates and a non-alumni Einstein faculty member are recognized for their contributions to science and medicine

By giving to Einstein, you advance the future of medical education, innovation, and discovery. Find a program to support today.

Make a Gift