In February 2021, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York launched a survey of more than 1,300 young people ages 14 to 24 from across the city.

Two of the most-striking findings: 35% of youths surveyed citywide—and half of those in the Bronx—said they wanted or needed mental health services from a professional, yet only 42% of those desiring mental health services reported receiving them.

All too many children and adolescents are plagued by depression, suicidal thoughts, anxiety, loneliness, isolation, sadness, or hopelessness—just a partial list of their mental health woes (see “Child and Youth Mental Health: By the Numbers,” below). Such problems are especially common in low-income areas, immigrant households, and minority communities—in other words, in places such as the Bronx. And everything related to mental health everywhere has been made worse by the lingering pandemic.

“Mental health challenges in children, adolescents, and young adults are real, and they are widespread,” writes U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, M.D., in a 2021 report, Protecting Youth Mental Health. “But most importantly, they are treatable, and often preventable.”

Dr. Murthy’s perspective may seem overly optimistic, but health professionals around the county are making real progress against the growing problem of child and adolescent mental illness—as shown by the work of dozens of Montefiore and Einstein psychologists and psychiatrists. Some of these efforts are described below.

Why you have to be like this?

You was really nice at first

But now you are really messed up to me.

Why you have to be like that?

This lyric was written not by a seasoned songwriter but by a 9-year-old Bronx boy. Carlos (not his real name) experienced abuse as a young child and was bullied later in school—traumas that have deeply affected him. He was at Montefiore’s Moses Child Outpatient Psychiatry Division (COPD) for counseling when his therapist, Jenny Seham, Ph.D., introduced him to Hear Your Song, a nonprofit organization that empowers children through songwriting.

“I said to Carlos, ‘My friends are musicians. Would you like to write a song with them?’ And just like that, he started singing,” says Dr. Seham. Carlos later returned to the COPD to join the songwriting program.

When there’s a block in therapy, the arts can often provide a way through. It’s an expansion of the ways we can reach our patients, in addition to traditional means.

— Dr. Jenny Seham

It’s one of the COPD’s more than half dozen Youth Empowerment Series (YES) programs aimed at helping children and adolescents come to terms with mental health issues, from post-traumatic stress disorder to depression to anxiety.

“The idea is to create a safe, therapeutic environment where kids, working individually and in groups, can actively explore whatever is troubling them, under the guidance of mental health professionals and local experts in the arts and other fields,” says Dr. Seham, founder and director of Montefiore Einstein’s Arts and Integrative Medicine (AIM) program, which oversees YES.

Launched in 2018, AIM offers 12- to 15-week sessions in songwriting, dance, yoga, photography, painting, poetry, and gardening, which are open to children ages 5 to 21 who are already receiving therapy at Montefiore. Each program culminates with a public exhibit or performance featuring the participants’ creations. Most prominent is the YES Art Gallery, a rotating art exhibition just off the main lobby of Montefiore Medical Center on 210th Street, curated and directed in collaboration with Fine Art at Montefiore Einstein.

The goal is to bring joy, inspire creativity, and provide health benefits. “Our programming is founded on evidence-based practices that have been shown to affect both mental and physical health,” says Dr. Seham. She was referring to a 2019 World Health Organization report, What Is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being?, which reviewed findings from more than 900 relevant publications from around the globe.

“When there’s a block in therapy, the arts can often provide a way through,” adds Dr. Seham, an artist, choreographer, dancer, and actor as well as a psychologist and an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Einstein. “It’s an expansion of the ways we can reach our patients, in addition to traditional means.”

Through her own studies, Dr. Seham is adding to the evidence in support of arts programming for youth with mental health issues. She also examines the impact of programs on the broader community, in and out of the hospital. In two recent studies, she found that the YES Gallery and the YES Community Garden positively influenced the mood of Montefiore employees (no small benefit for workers in such a high-stress environment) and could help reduce the stigma associated with mental illness.

As for Carlos, the YES songwriting program certainly appears to be working. “He ended up writing a whole song about ‘going through the dark and coming into the light,’” says Dr. Seham. “He tells me he sings it all the time at home.”

“Our programming is founded on evidence-based practices that have been shown to affect both mental and physical health.”

— Dr. Jenny Seham

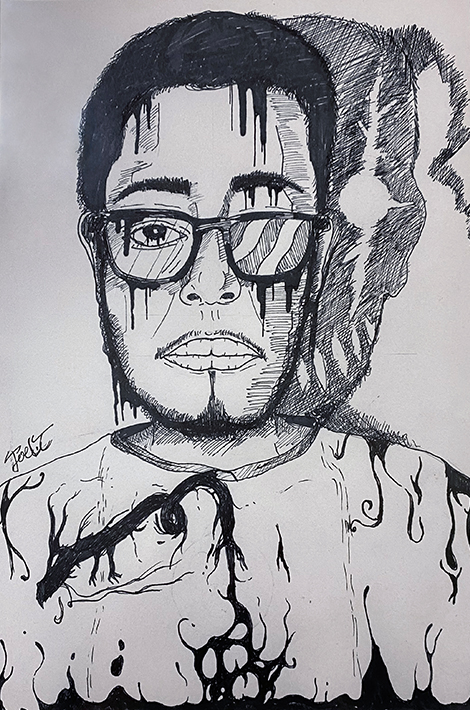

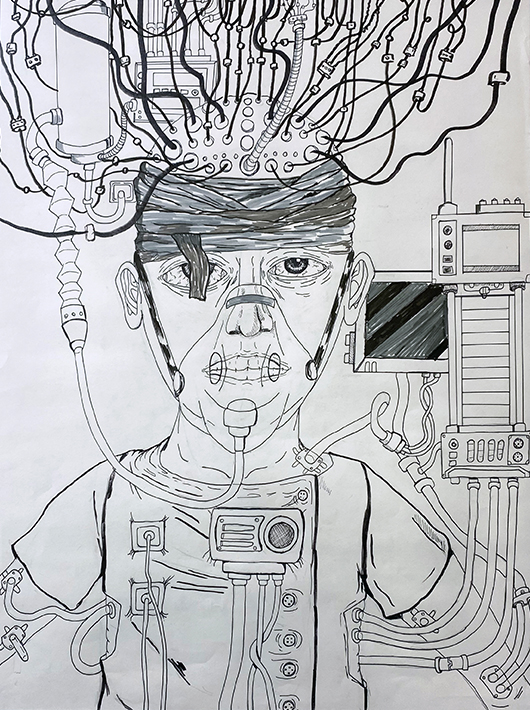

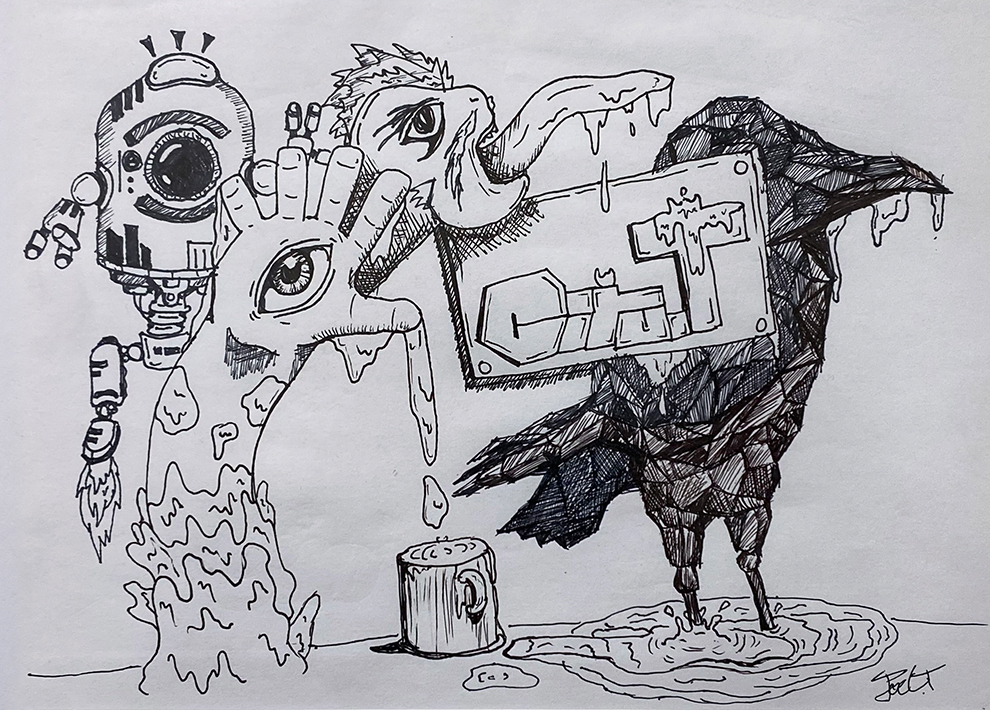

I want to help others who are dealing with mental health issues understand that they can actually enjoy life.

— Artist Ciro Joel Trinidad

When she learned that Ciro was interested in drawing, Dr. Seham urged him to join the Youth Empowerment Series (YES) Arts Group, a component of Montefiore Einstein’s Arts and Integrative Medicine, or AIM, program. There, psychotherapists and professional artists use the arts to create a healing environment for children and adolescents with mental health issues. Ciro started drawing again and impressed everyone with his talent.

His social skills flourished along with his artistic skill. “It distracted my mind from all my other problems and gave me practice socializing and communicating,” he says.

In 2022, Dr. Seham invited Ciro to exhibit his works in the YES Art Gallery at Montefiore, but the invitation awakened painful childhood memories: classmates had ridiculed his artwork back in elementary school. “I would hide my drawings from my teachers, from other students,” he recalls. But with his newfound confidence, Ciro agreed to exhibit his work.

“I’m still working on my issues,” admits Ciro, now 21. “I can’t say I’m happy or sad, more like in between, neither in the light nor in the dark.”

But there’s a much brighter side to his remarkable story. Today, he’s cancer free and attending the Borough of Manhattan Community College, majoring in animation and motion graphics. He has since graduated from the YES program but remains active as an AIM ambassador, mentoring children in the Arts Group. “I want to help others who are dealing with mental health issues understand that they can actually enjoy life,” says Ciro.

Last year, Montefiore honored him with its annual AIM Ambassador Award in recognition of his artistry, mental health advocacy, and service to the community.

“This program should be expanded to other hospitals,” says the young artist. “It has so much potential.” The same could be said about Ciro.

That old medical-school joke—“Half of everything we teach you is wrong, but we don’t know which half”—has the ring of truth when it comes to teens stricken by major depressive episodes: doctors know that half of them will fully recover, while the other half will develop severe depression or a chronic mood disorder—but doctors can’t predict who will recover and who won’t.

“In psychiatry, we diagnose depression from symptoms, but that can be subjective, and it doesn’t give us much insight into a patient’s prognosis,” says Vilma Gabbay, M.D., professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and in the Dominick P. Purpura Department of Neuroscience at Einstein. “I would argue that this is particularly important for depression, since it’s associated with suicide, the second-leading cause of death in adolescents and young adults.”

Depression is characterized by persistent feelings of sadness or irritability and decreased ability to experience pleasure (anhedonia). The condition is poorly understood biologically and has a range of possible causes, including genetics, stressful life events, and medical conditions.

“My lab is focused on identifying the neurobiological mechanisms that underlie adolescent depression and that may predict outcomes,” says Dr. Gabbay, who is also the director of the Psychiatry Research Institute at Montefiore Einstein (PRIME) Center for Biomarkers and Dimensional Psychiatry.

We hope our study will identify objective diagnostic criteria for adolescent depression and will lead to targeted therapies that address the underlying causes of the condition and not just the symptoms.

— Dr. Vilma Gabbay

She has a good idea where to start looking. In previous research, Dr. Gabbay found that, of all the core symptoms of adolescent depression, only anhedonia—the inability to feel pleasure—was associated with worse outcomes, including an increased risk of suicide. The discovery suggests that impaired brain-reward circuitry—which controls the ability to feel pleasure—might cause severe cases of teen depression to continue.

Using brain imaging to look deeper, Dr. Gabbay found that depressed adolescents have abnormally low levels of GABA (the brain’s major inhibitory neurotransmitter), plus abnormal activation patterns in brain regions related to anticipating and attaining reward (the “planning” and “receiving” components of reward processing). Dr. Gabbay also found that immune system irregularities, including elevated levels of interferon and other inflammatory proteins, were associated with anhedonia severity and abnormal reward circuitry in adolescents.

Now, in a new study supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, Dr. Gabbay is taking a more comprehensive look at how reward dysfunction and immunological abnormalities might contribute to adolescent depression. She plans to enroll a diverse group of 120 adolescents with depressive symptoms and follow them over two years.

The teens will receive comprehensive clinical evaluations, and those diagnosed with clinical depression will take computerized tests designed to engage and measure their reward circuitry. The researchers will look for known biomarkers of inflammation and measure participants’ GABA levels. In addition, the teens will undergo functional magnetic resonance imaging during the reward testing to evaluate their ability to feel pleasure, depression severity, functioning, anxiety, and risk of suicide.

“We hope our study will identify objective diagnostic criteria for adolescent depression and will lead to targeted therapies that address the underlying causes of the condition and not just the symptoms,” says Dr. Gabbay.

It was obvious from the start of the pandemic: although children were largely resistant to the disease, they were all too susceptible to the anguish it caused—fear of or grief about losing a parent; social isolation; the difficulties of remote learning.

Clinicians were in uncharted territory, uncertain how best to respond to this novel threat to pediatric mental health. “But we knew from decades of research that child resilience is tied to caregiver resilience,” says Sandra Pimentel, Ph.D., chief of child and adolescent psychology at Montefiore and Einstein and an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Einstein. So Montefiore’s experts in psychiatry and behavioral sciences and in pediatrics began extending lifelines to parents, both on the staff and in the community.

Drawing in air by expanding the belly can help your child relax and reduce heart rate, blood pressure, and stress hormones.

Helping your child focus on what’s around them, what they see and hear, can help pull your child away from the anxiety and ground them in the present moment. Doing activities together (playing a game) that can bring their attention into the present moment is another way to practice.

Teach your child to talk back to their worries—”Even though I’m scared, I can handle it.” “I’m stronger than my worries.”

Teach your child that when you have to do something that makes you nervous, it helps to plan in advance how to help yourself in the moment. If you can push through it, it will get easier!

Help your child acknowledge discomfort without fighting it. Ignoring, judging, or avoiding the anxiety will likely make it grow bigger and more powerful. Teach them that everyone feels anxious at times, and that it is OK to feel anxious. You can feel anxious and do things that are important to you anyway.

Through a community speakers bureau she created, Dr. Pimentel and colleagues gave dozens of talks in neighborhoods throughout the Bronx and met with organizations such as parent-teacher and faith-based groups. They developed parent support groups, created a confidential emotional support line for caregivers, produced tip sheets on such topics as “Helping Kids Cope with Grief and Loss,” and led grand rounds such as “Supporting Family and Child Emotional Health During COVID-19.”

Help was also offered to teens and young adults directly affected by the pandemic. Dr. Pimentel and her colleagues in the Becoming an Emerging Adult at Montefiore (BEAM) program collaborated with local Bronx youth to conduct virtual town halls discussing loneliness and isolation.

Meanwhile, Einstein professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences Vilma Gabbay, M.D. was awarded a $4.1 million National Institutes of Health grant to study interventions to reduce pandemic-related symptoms of depression and anxiety among Bronx caregivers.

The randomized trial will evaluate three approaches. One-third of the 360 participants will receive 12 weeks of group telehealth therapy, expanding on the work of Connecting and Reflecting Experience (CARE), a group-based program at Montefiore and Einstein developed by Amanda Zayde, Psy.D., assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Einstein and psychologist at Montefiore. Another third of the participants will receive 12 weeks of parenting education supported by the Valera Health smartphone app, with a focus on teaching caregivers problem-solving, communication, and coping skills. The final third will receive both interventions.

“As a psychiatrist and a mom, I want caregivers in the Bronx to have the tools to be confident in tough parenting situations and tackle stress and uncertainty in a healthy way,” says Dr. Gabbay.

Reading, as Shakespeare realized, has the power to soothe troubled souls. Four centuries later, the bard’s insight has been formalized into “bibliotherapy,” a type of psychotherapy in which people read carefully selected materials that help them cope with mental health issues. Bibliotherapy has now entered the digital realm and found its way into social media platforms designed to support people at risk for suicide and other personal crises.

One proponent of digital bibliotherapy is Peter Franz, Ph.D., a postdoctoral research fellow at PRIME, who studies ways to prevent self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. “Loneliness is a major risk factor for suicide,” says Dr. Franz. “The question is, how can we create connections between people that are reparative and therapeutic?”

If you ask patients in your office if they’re thinking about hurting themselves, they may say ‘No’—but that could change five minutes after they walk out the door.

— Dr. Peter Franz

The standard approaches to suicide prevention—traditional psychotherapy and medical treatment—could certainly be improved upon. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide rates have barely budged over the last century, and suicide now ranks as the second-leading cause of death among individuals ages 15 to 44.

“There’s a great need for new approaches, particularly ones that are low cost, engaging, accessible, and scalable,” says Dr. Franz. Digital bibliotherapy appears to fit the bill.

“We all know that people can engage in potentially harmful communication online,” Dr. Franz acknowledges. “But there are also places online that offer a supportive environment where people are comfortable being themselves and where there’s less stigma associated with talking about mental health concerns such as suicide. We know that young people at risk for suicide are engaging in online discussions at a higher rate than their age-matched peers, and linking them up with a supportive online community might be incredibly helpful.”

Could such an online resource work as intended? To find out, Dr. Franz tested the impact of digital bibliotherapy on 528 adults—each with a history of suicidal thoughts—who were randomly divided into two groups. One group read short stories on a social media platform that describe firsthand experiences with suicidal thoughts and recovery from having those thoughts. People in the second group were placed on a waiting list for the platform. After two weeks, participants who read the stories reported significantly less intense suicidal thoughts compared with people on the waiting list, according to Dr. Franz’s paper, which was published in August 2022 in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology.

“The effects were relatively modest,” Dr. Franz says. “But the big upside is that this intervention can be given to anyone, anywhere, and at very low cost. And it can be given anytime, with no waiting to talk to a therapist or get a prescription.” He is now planning to test the digital bibliotherapy intervention on adolescents.

“We know that young people at risk for suicide are engaging in online discussions at a higher rate than their age-matched peers, and linking them up with a supportive online community might be incredibly helpful.”

— Dr. Peter Franz

Dr. Franz has done research with TeenHelp.com and TheMighty.com—websites that provide online support for people experiencing mental health challenges—and is also exploring other ways to use digital technology to support young people at risk.

“Suicidal thoughts tend to ebb and flow quite a bit, even during the course of a single day,” he explains. “If you ask patients in your office if they’re thinking about hurting themselves, they may say ‘No’—but that could change five minutes after they walk out the door. We need a way to assess suicidal thoughts and engage with people more regularly.”

One solution, Dr. Franz believes, is to use a smartphone app to check in on people several times a day. “In theory, we could more accurately assess their suicide risk and provide interventions in a timelier manner,” he says. “We could also use the app to better understand what life events tend to trigger suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Then we could intervene before those thoughts and behaviors ever materialize. I’d say that a very large proportion of individuals who are thinking about suicide are not receiving treatment,” continues Dr. Franz. “That’s a challenge we need to overcome.”

Navigating adolescence is tough—and often much tougher for teens who regularly encounter racism. Some are naturally resilient and able to weather those stresses, but others suffer significant psychological harm, especially those already coping with mental health issues.

“Racism has been around forever. Over the past few decades researchers have amassed enough evidence to unequivocally show that it can be harmful, emotionally and physiologically—exacerbating everything from anxiety to depression to suicidal ideation,” says Ryan DeLapp, Ph.D., who was until recently an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Einstein.

The problem now has its own name: racism-related stress (RRS), defined as psychological distress stemming from direct or indirect experiences of racism, ranging from racial microaggressions (subtle, intentional, or unintentional degradations and exclusions that may be imperceptible to others) to overt acts of discrimination in everyday life (e.g., in school, at work, in social situations).

A recent twist to RRS is the near-constant depiction of racism in the broader culture, such as cable news and social media after events such as the murder of George Floyd.

Racism has been around forever. Over the past few decades researchers have amassed enough evidence to unequivocally show that it can be harmful, emotionally and physiologically.

—Dr. Ryan DeLapp

“The natural reaction is to want to learn more, to make sense of it all,” says Dr. DeLapp. “More information is better, right? But it can set off endless ‘doomscrolling,’ where information overwhelms your ability to absorb it.” The endless replays of acts of violence against people of color—a staple of cable news coverage—can also be traumatizing, experts say. And making matters worse, few mental health professionals are prepared to help young people who experience RRS.

While he was a full-time faculty member at Einstein, Dr. DeLapp and his colleague Laurie Gallo, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Einstein and a psychologist at Montefiore, worked to fill this underappreciated gap in clinical care. Together they developed REACH UP (Racial, Ethnic, and Cultural Healing Unifying Principles), a therapeutic framework designed to help clinicians identify and treat adolescents and young adults affected by RRS.

REACH UP aims to empower patients by identifying challenges that hinder the ability to embrace their racial/ethnic identity, and developing both acute and long-term mechanisms for coping with the intense emotional discomfort associated with racism. The intervention unfolds over six to eight therapy sessions.

Drs. DeLapp and Gallo aren’t the first to prescribe remedies for RRS. However, their approach is the first to target clinicians of varying training levels, cultural backgrounds, and theoretical orientations. REACH UP is not a standalone therapy; it was devised to supplement other psychotherapeutic approaches.

“In most clinical settings, particularly hospital-based outpatient psychiatric clinics, patients present with other mental health issues. RRS is rarely, if ever, a primary reason why they are seeking help. Our approach was therefore crafted to be flexible enough to work within a patient’s overall treatment plan,” says Dr. DeLapp, whose treatment guide was published in November 2022 in the Journal of Health Service Psychology.

In March 2023, Dr. DeLapp took on a new position: launching the REACH UP program at a group practice serving youths and young adults across several states. He continues working as a part-time clinician at Einstein and Montefiore, focused on helping young people cope with stress related to racism.

Of the many projects she has helped lead, Sandra Pimentel, Ph.D., may be most proud of Superkids: Change the World, an interactive comic book that helps hospitalized children—particularly those spending long stretches away from school, friends, and family—cope with the adversities of illness.

The idea for Superkids came from Chase Masterson, an actor who founded the Pop Culture Hero Coalition, which uses superhero comic book imagery and narratives to help children develop social and emotional skills. She wanted to honor Bronx comic book writer Len Wein, who’d been hospitalized as a kid—and whose lifelong love of comics was sparked by the comic books his father brought to keep him occupied. A comic book supporting other children in that predicament seemed like the perfect tribute.

Superheroes are born of adversity. What makes them heroic is their ability to overcome their personal monsters.

— Dr. Sandra Pimentel

For help in realizing this idea, Ms. Masterson turned to Dr. Pimentel, chief of child and adolescent psychology at Montefiore and Einstein and associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Einstein, and Janina Scarlet, Ph.D., psychologist and author of the book Superhero Therapy. Dr. Pimentel worked with colleagues in pediatrics to identify the greatest psychological challenges that hospitalized kids face (fear, pain, loneliness, and depression) and strategies for coping with those “monsters” in the superhero lexicon.

“Superheroes are born of adversity,” says Dr. Pimentel. “That’s their origin story. But what makes them heroic is their resilience and their ability to overcome their personal monsters. In Superkids, we ask kids to identify their monsters and we introduce them to the special evidence-based skills, or ‘power-ups,’ that they can wield to defeat the monsters.”

Young readers of Superkids are introduced to mindful breathing and other power-ups, asked to identify their own heroes, encouraged to build their social support teams with sidekicks such as pets and friends, and, ideally, become inspired to help other kids in need. (Bronx readers may notice that the comic’s cover shows the Superkids bursting from the entrance of CHAM on Bainbridge Avenue.)

Judging from a small initial pilot study, Superkids is an easy-to-read, accessible format for teaching evidence-based skills for coping with pain and adversity. “It was really helpful, and I felt more positive after reading the comic book,” one young reader commented.

The team is now conducting a randomized clinical trial testing how best to deliver Superkids in the hospital setting. It is also modifying Superkids to address the interests and needs of older kids.

“In Superkids—and for that matter in all of our work—we’re trying to be creative in how we deliver care,” says Dr. Pimentel. “It doesn’t have to be sitting a patient in a chair and saying, ‘Let’s do therapy.’”