-

-

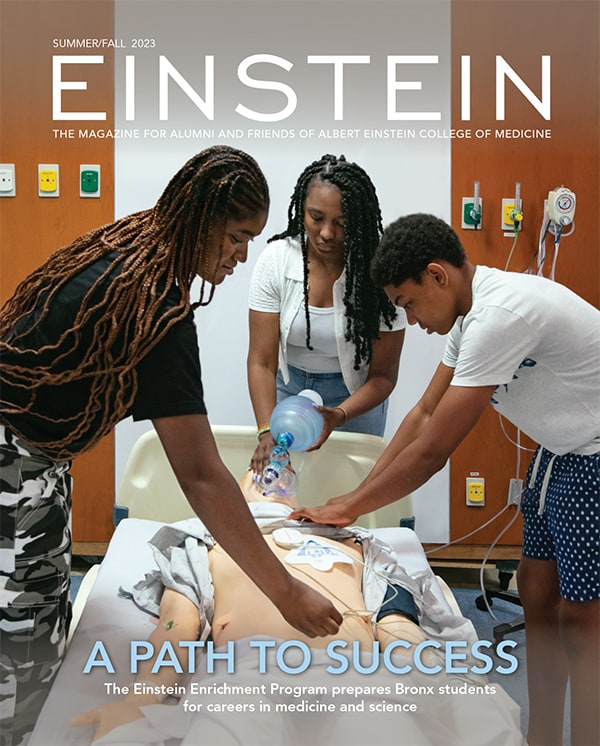

Preparing for the Next Pandemic

Preparing for the Next PandemicEinstein scientists are working to make the United States and the world better equipped for the next widespread infectious disease—whether it’s caused by newer microbes or age-old killers

-

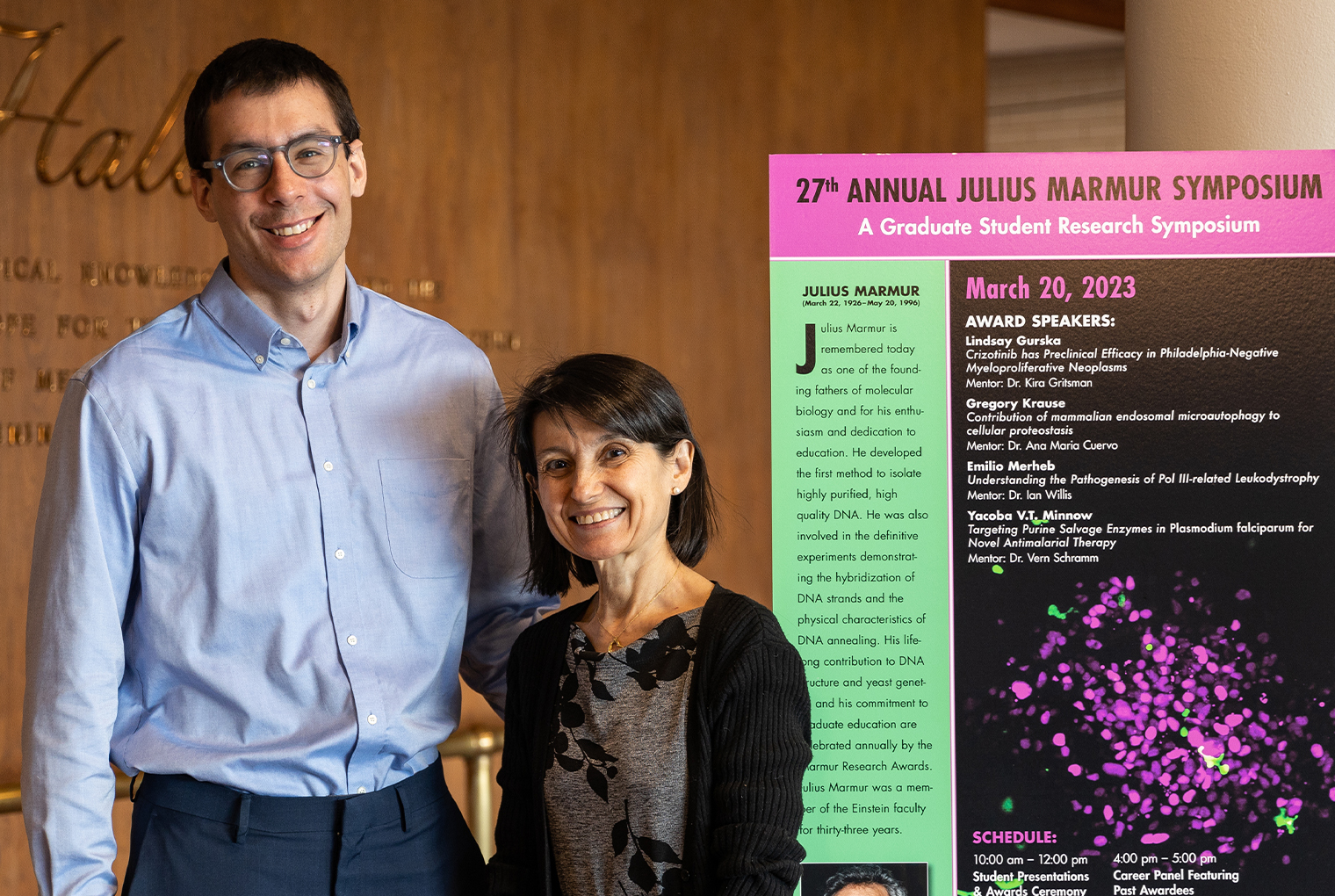

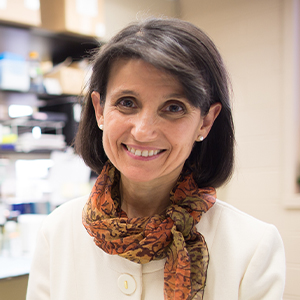

Celebrating 60 Years of Training Physician-Scientists

Celebrating 60 Years of Training Physician-ScientistsGraduates of the Medical Scientist Training Program play a critical role in advancing medicine as clinicians and researchers

-

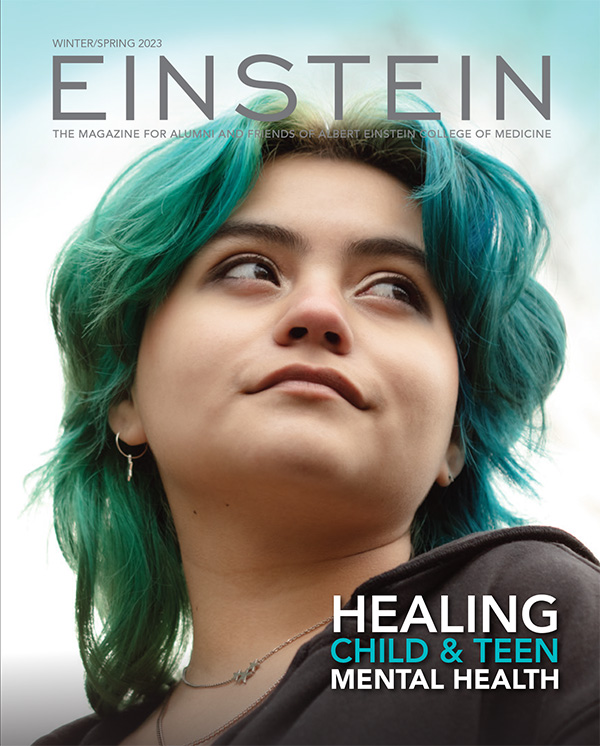

When the Emergency Department Is Not Enough

When the Emergency Department Is Not EnoughA new inpatient pediatric facility will answer an urgent need to help children experiencing a psychiatric crisis

-

Lupus: Giving Voice to a Silent Disease

Lupus: Giving Voice to a Silent DiseaseAn innovative institute in the Bronx breaks new ground in the fight against lupus

-

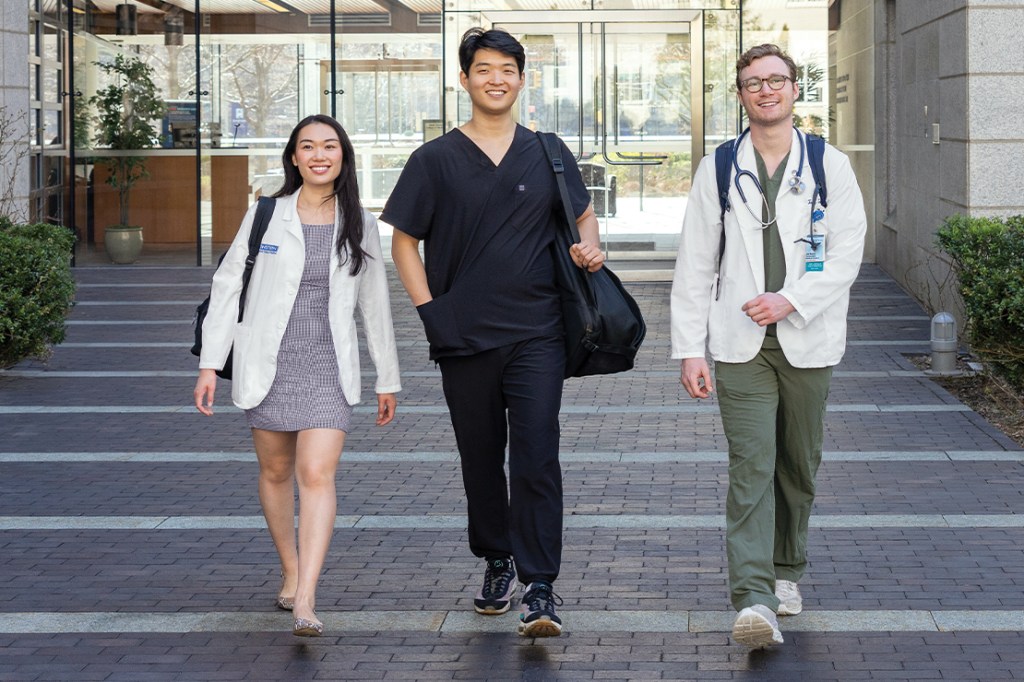

An Unconventional Path to Medicine

An Unconventional Path to MedicineThree nontraditional medical students—a former actor, nurse, and businessperson—bring fresh perspectives to the classroom

-

Students Get a New Home Away From Home

Students Get a New Home Away From HomeReading nooks. A pool table. Dedicated storage. Albert’s Den, a new two-story student lounge, brings many of the comforts of home

-

Message From the Dean

Message From the DeanYaron Tomer, M.D., discusses the historic gift and what it will mean to the College of Medicine

-

Message From the Board Chair

Message From the Board ChairRuth Gottesman, Ed.D., provides an update on philanthropy, trustee news, and more

-

Remembering Former Einstein Board Chair Ira Millstein

Remembering Former Einstein Board Chair Ira MillsteinAn ardent leader and steadfast supporter, he served the College of Medicine for more than four decades

-

Einstein Appoints Endowed Chairs, Faculty Scholars

Einstein Appoints Endowed Chairs, Faculty ScholarsThe Board of Trustees recognizes faculty accomplishments in diabetes research, translational medicine, and more

-

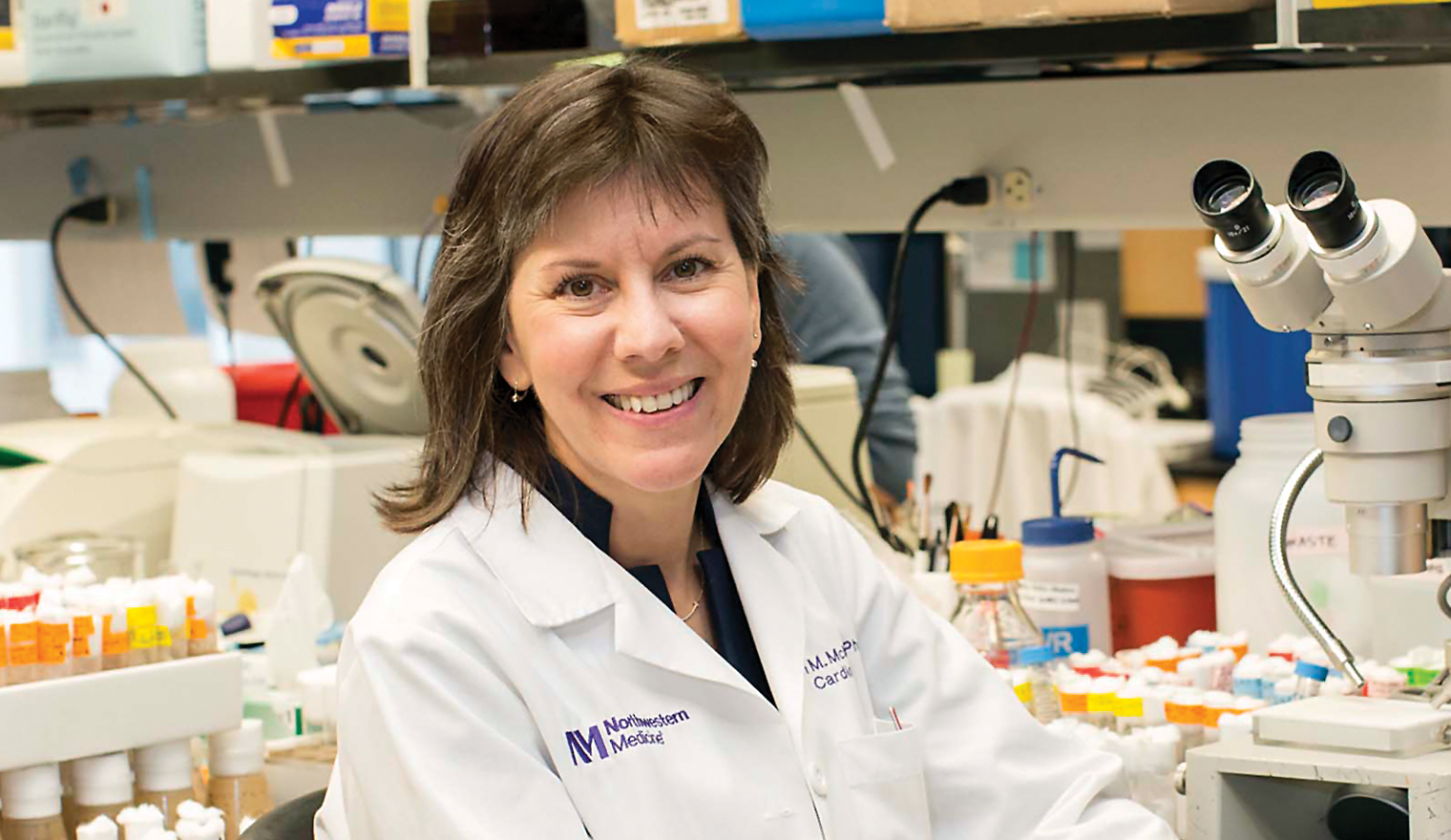

Lab Chat With Dr. Maria Soledad Sosa

Lab Chat With Dr. Maria Soledad SosaMaria Soledad Sosa, Ph.D., studies cancer-cell dormancy, in which cancer cells hibernate and then reactivate

-

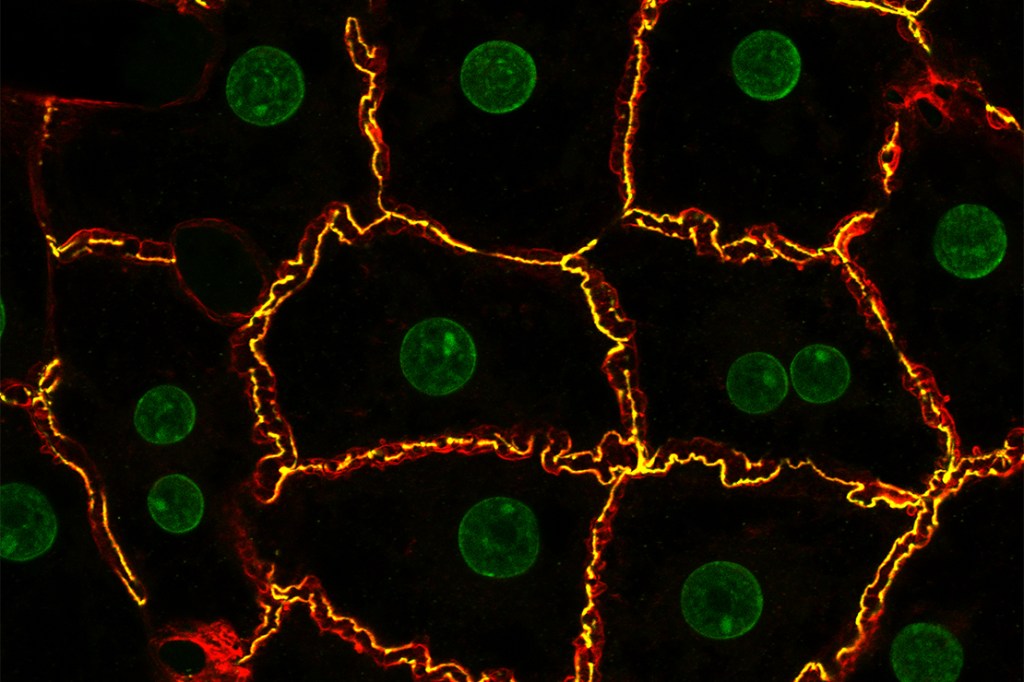

Einstein Image: Hepatocytes

Einstein Image: HepatocytesVisualizing the bile canaliculi, the tiny channels into which hepatocytes (the predominant cell type in the liver) secrete bile

-

Honoring the ECHO Free Clinic at Its Annual Gala

Honoring the ECHO Free Clinic at Its Annual GalaAlumni, students, and supporters gathered to celebrate the Einstein Community Health Outreach Free Clinic

-

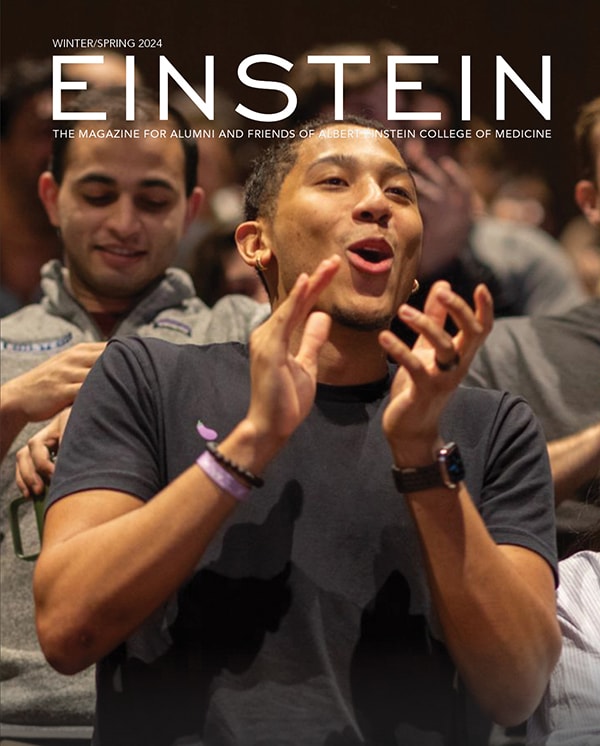

Einstein Celebrates Its 66th Commencement

Einstein Celebrates Its 66th CommencementFormer CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, M.D., delivers keynote at Lincoln Center

-

The Sun Shines on Montefiore Einstein in Florida

The Sun Shines on Montefiore Einstein in FloridaWeek’s events showcase Montefiore Einstein experts, achievements in philanthropy, and scientific advances

-

Inaugural Vice Dean for Education Appointed

Inaugural Vice Dean for Education AppointedDr. Yoon Kang, a nationally recognized leader, will oversee all educational programs

-

Class Notes: Winter/Spring 2024

Class Notes: Winter/Spring 2024Updates from graduates across the decades, from the 1950s to the 2020s

-

In Memoriam: Winter/Spring 2024

In Memoriam: Winter/Spring 2024Recently deceased members of the Einstein and Montefiore communities

-

A Look Back: Pediatric Rounds

A Look Back: Pediatric RoundsThe affiliation between Einstein and Montefiore began 60 years ago

-

Letter to the Editor

Letter to the EditorReaders respond to the Summer/Fall 2023 issue of Einstein magazine

-

The Dean’s Society: Unrestricted Support

The Dean’s Society: Unrestricted SupportThe Dean’s Society celebrates the impact of Einstein donors who provide leadership with unrestricted support—flexible funds to use when and where they are needed most

-

Legacy Society: Arthur Schapiro, M.D. ’62

Legacy Society: Arthur Schapiro, M.D. ’62The Legacy Society recognizes individuals who choose to advance Einstein’s mission through gifts in their estate plans

By giving to Einstein, you advance the future of medical education, innovation, and discovery. Find a program to support today.

Make a Gift