Error: No layouts found

You could say that bad weather has guided Dr. Sten Vermund’s life. In 1973, he received an offer letter from the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF)—his first-choice medical school. He had applied to Einstein, but the pace and culture of New York were intimidating to the Norwegian American who grew up in the Midwest. He was finishing a B.A. in human biology at Stanford and intended to stay in California. Still, he accepted Einstein’s admissions interview out of curiosity and on the recommendation of his Stanford advisor, a child psychiatrist who had trained at Montefiore.

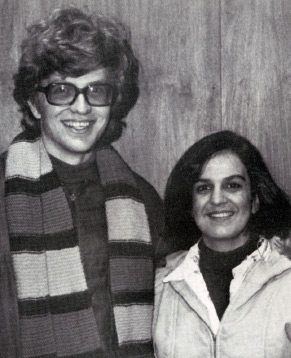

Sten Vermund met his wife-to-be, Pilar Vargas, in histology class at Einstein. The two have been married for nearly 40 years.

That admissions interview coincided with a severe winter ice storm that paralyzed public transportation. He took the subway in from Queens, where he’d stayed with a friend, and was stuck for an hour on a cold, snowy platform. He recalls the “unusually loquacious and friendly” straphangers he met there—a diverse group that “violated all my New York City stereotypes.” The subway trip took more than three hours, but he arrived at Einstein just in time.

Few other prospective students had braved the storm, so Dr. Vermund spent more than triple his allotted time learning about Einstein and its mission. What he heard matched his own interests—in social justice, community engagement and tackling health disparities in underserved communities.

Dr. Vermund turned down UCSF and enrolled at Einstein. “I had a feeling about Einstein that continues to this day—I just fell in love with it,” he says.

Not long afterward, he fell in love with his lab partner too. Thanks to Einstein’s practice of assigning students to classroom seats alphabetically, Dr. Vermund found himself next to Pilar Vargas in first-year histology. Dr. Vargas, who already had a Ph.D. in developmental biology when she enrolled at Einstein, soon began mentoring the “goofy” younger man (as she described him to friends) through several classes together, and Dr. Vermund began to appreciate her nonscientific attributes. “I was persistent,” he says of their eventual union. In 2017, they celebrated their 39th wedding anniversary. They have two adult sons.

That 1973 ice storm altered Dr. Vermund’s career as well as his personal life. He had intended to become a child psychiatrist, but his Einstein experience led him instead to pediatrics. After graduating from Einstein, he went to developing countries to conduct epidemiology studies on infectious diseases. He later spent six years with the National Institutes of Health, 11 years as a professor at the University of Alabama and 12 years at Vanderbilt University, where he founded Vanderbilt’s Institute for Global Health. He now serves as dean of the Yale School of Public Health and is an international leader in HIV/AIDS and global health research.

Dr. Vermund came to Einstein by chance, but he has stayed connected by choice—including through service on Einstein’s Alumni Board of Governors. He and Dr. Vargas are generous and loyal supporters, helping younger generations receive the same superior education, resources and access they enjoyed. “I feel the same way about Einstein that I did after that 1973 interview,” he says. “It really is a very special place.”