If someone were to design the perfect setting for an asthma epidemic, it would probably look like the Bronx. New York’s northernmost borough has every ingredient for making asthma flourish: plentiful outdoor respiratory irritants and indoor allergens, a genetically susceptible population (prevalence is highest among blacks and Puerto Ricans), a high rate of obesity (now recognized as an important cause of asthma), a preponderance of poverty (low-income households are especially hard-hit) and inadequate referrals to specialty care. The problem is particularly acute for children.

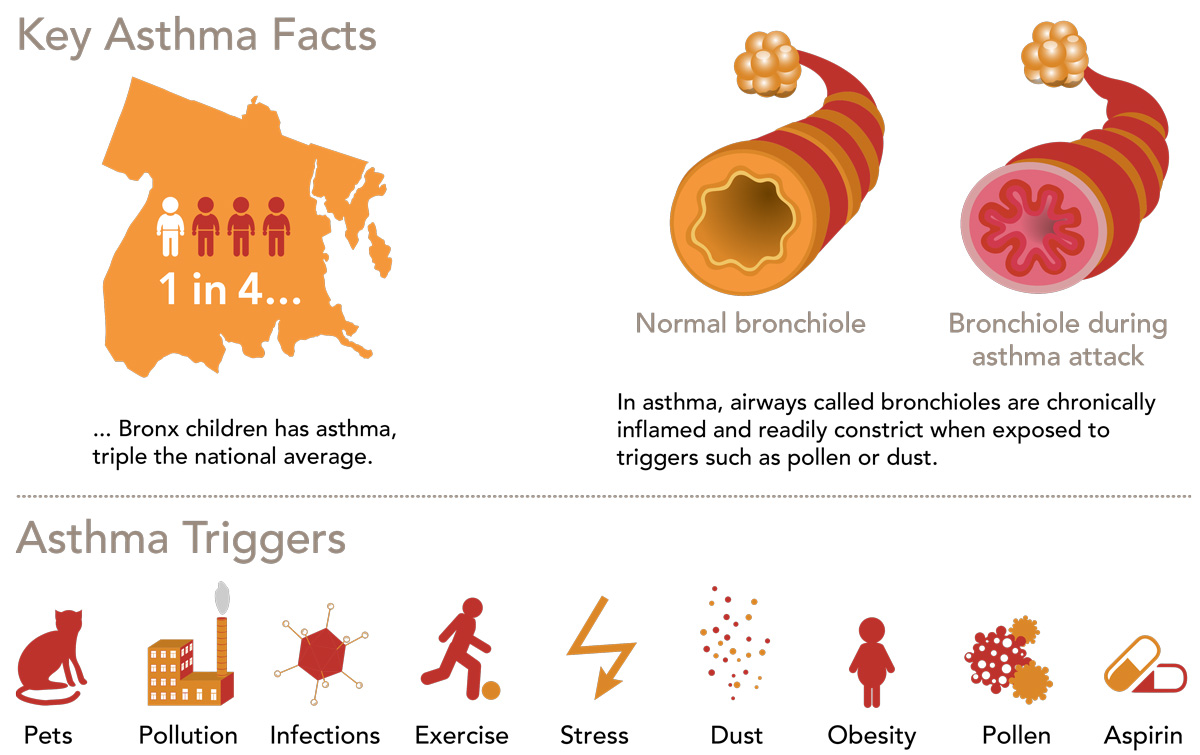

One in four Bronx children has asthma—triple the national average. Bronx children with asthma are hospitalized at twice the rate for asthmatic children in New York City as a whole, and quadruple the rate for asthmatic kids nationally. Bronx adults are also disproportionately affected. Data from the New York State Department of Health show that the death rate from asthma in the Bronx is nearly double the rate for New York City as a whole, with some 50 Bronx residents (most of them children) dying from the disease each year.

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease that can affect people of any age, but it usually starts in childhood. More than 25 million Americans—seven million of them children—have the disease. Each year, asthma costs the country $56 billion and accounts for 640,000 emergency-room (ER) visits, 157,000 hospitalizations and 4,000 deaths.

When people have asthma, the bronchioles—airways that carry the air we breathe into our lungs—are chronically inflamed. This inflammation leads to airway constriction that causes asthma’s recurring symptoms: wheezing, chest tightness, shortness of breath and coughing. Patients are hypersensitive to certain triggers that keep their airways inflamed and periodically set off symptoms or worsen them to the point of causing life-threatening asthma attacks.

More than half of people with asthma have “allergic asthma.” Their triggers include pollen, mold, particles from cockroaches and dust mites, animal dander and other allergens that provoke their immune systems to release inflammatory chemicals that affect the airways. For most other asthma cases, the causes of airway inflammation and other symptoms include obesity, cold air, strenuous physical exercise, chest infections, air pollution (from tobacco smoke, household cleaning products and ozone, for example) and aspirin sensitivity, which all too often goes undiagnosed.

(See “Hair of the Dog Helps Long-Suffering Asthma Patient” below.)

Since there is no cure for asthma, proper care involves controlling the disease to prevent serious complications: flare-ups that cause absences from school or work; severe attacks that lead to ER visits and hospitalization; and, most importantly, permanent narrowing of the bronchial tubes. Controlling asthma means avoiding triggers (sometimes with the aid of allergy shots) and taking drugs that tame inflammation and open airways when symptoms occur.

Two types of drugs are used for treating asthma. So-called long-term control medicines (primarily inhaled corticosteroids) are taken daily to quell airway inflammation and prevent asthma symptoms. When asthma flare-ups occur, short-acting “rescue” bronchodilator drugs can quickly relax constricted bronchial-tube muscles.

Simon Spivack, M.D., and David Rosenstreich, M.D., are co-directors of the Monte ore Asthma Center.

Simon Spivack, M.D., and David Rosenstreich, M.D., are co-directors of the Monte ore Asthma Center.

Coughing persistently at night as well as during the day…experiencing wheezing or other asthma symptoms more than twice a week…needing increasingly high drug doses to keep symptoms at bay: all are indications of uncontrolled asthma. Alarmingly, nearly half of Bronx children with asthma have uncontrolled disease —putting them at risk for poor cardiovascular fitness, obesity and psychosocial problems such as depression, anxiety and learning disabilities.

Einstein and Montefiore have responded to the asthma emergency in their borough with a wide-ranging research effort and community programs and clinics, including the Montefiore Asthma Center. Since 2011, it has served as the Bronx’s only referral center for children and adults with persistent or uncontrolled asthma—a life-altering and potentially fatal condition.

Gaining control over their asthma can make a world of difference for patients, and the Montefiore Asthma Center helps them attain that goal.

“When we created the asthma center, we decided that all patients must receive what is considered the gold standard in asthma care: consultations with both an allergist [in part for allergy testing] and a pulmonologist [in part for spirometry, or lung-function measurement],” says Simon Spivack, M.D., co-director of the Montefiore Asthma Center, chief of the division of pulmonary medicine at Einstein and Montefiore and professor of medicine, of epidemiology & population health and of genetics at Einstein. He notes that the clinic staff also includes an asthma educator—vital for a disease that requires patients to take on significant responsibilities for their own care.

“Most cases of asthma can be managed, but it takes a lot of work,” says David L. Rosenstreich, M.D., who co-directs the asthma center along with Dr. Spivack and is chief of the division of allergy and immunology at Einstein and Montefiore, and professor of medicine, of microbiology & immunology and of otorhinolaryngology and the Joseph and Sadie Danciger Distinguished Scholar in Microbiology/Immunology at Einstein.

“The first thing we do,” says Dr. Rosenstreich, “is make sure that the patient actually has asthma. About 20 percent of our patients have some other condition, such as vocal-cord dysfunction or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which masquerades as asthma. And then there’s the challenge of determining the severity of the disease, which dictates treatment.”

The asthma center is supported by clinicians and scientists at Einstein and Montefiore who ensure that treatment guidelines are implemented, help patients self-manage their disease and reduce their exposure to household allergens and other asthma triggers, and investigate how factors such as obesity contribute to asthma.

Karen Warman, M.D., center, with pediatric residents Jesil Pazhayampallil, left, and Kyle Hengel.

Karen Warman, M.D., center, with pediatric residents Jesil Pazhayampallil, left, and Kyle Hengel.

A key asthma treatment guideline calls for pediatricians to refer every child with poorly controlled asthma to an allergist and a pulmonologist. (As noted above, the Montefiore Asthma Center offers such care to all patients.) “These specialists conduct tests essential for diagnosing asthma severity and prescribing treatment,” says Karen Warman, M.D., an associate professor of pediatrics at Einstein and a pediatrician at Montefiore’s Comprehensive Family Care Center. “They also help us convince parents that their child needs to take medications. There’s little we can do to improve their child’s condition if parents aren’t on board with the care plan.”

But national surveys have shown that pediatricians routinely ignore this guideline. In response, Dr. Warman launched a retrospective study of care delivered to 4,600 children (ages 7 to 17) with uncontrolled asthma. The results, published in 2017 in the

Journal of Asthma, were even worse than she expected.

“Just 19 percent of the children had seen an allergist or pulmonologist,” she says. “Even more disturbing, only 42 percent of those with an asthma-related hospitalization—a red flag for a referral—had seen a specialist. These kids weren’t getting the care they needed.

“We in primary care must do a better job of identifying children with uncontrolled asthma and making referrals,” she adds. “We have to ask questions, digging deep into symptoms and medication use, and we need to do hands-on demonstrations to show kids how to use asthma devices. They’re complicated. You can’t just prescribe them and send the patient off.”

Dr. Warman believes that, with proper training and resources, primary care providers can improve the asthma care they offer patients. She conducted a pilot study that enrolled 79 inner-city children in a primary care–based program applying national asthma treatment guidelines, which include spirometry testing. The children were significantly more likely than they had been under their previous routine care to be identified as having moderate or severe persistent asthma, to be prescribed inhaled steroids and to have their medication plans intensified. After participating in the program, fewer of the children needed trips to the ER: 32% had asthma-related care in the ER in the 12 months prior to the program and only 8% did in the 12 months following the program.

“Asthma is a controllable illness,” Dr. Warman notes. “Given the right treatment regimen, most patients can be healthy and active.”

Karen Warman, M.D., center, with pediatric residents Jesil Pazhayampallil, left, and Kyle Hengel.

Karen Warman, M.D., center, with pediatric residents Jesil Pazhayampallil, left, and Kyle Hengel.

Barbara Roseval of East Hempstead, NY, lived this nightmare, with symptoms that started during her first pregnancy. An allergist prescribed allergy shots, but her condition only grew worse. She soldiered on for years while raising three kids and working as a paralegal. “My nose was like a fountain,” she says. “I should have bought stock in Kleenex.”

Barbara eventually went to a second allergist, who suggested she might have aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD)—a poorly understood trio of conditions including asthma; sinus disease with recurrent nasal polyps; and sensitivity to aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. People with AERD may constitute as many as one out of 10 asthma cases.

While Googling her condition, Barbara came across an AERD specialist in the Bronx: Elina Jerschow, M.D., an associate professor of medicine at Einstein and an attending physician in pediatric and adult allergy and immunology at Montefiore. “I e-mailed her on a Saturday evening, hoping I would hear back in a few days,” Barbara recalls. “She responded within an hour.”

“I see many patients like Barbara who have been going from doctor to doctor without getting a proper diagnosis,” says Dr. Jerschow. “The average time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis is about three to five years.”

Dr. Jerschow confirmed that Barbara did indeed have AERD and began treating her with aspirin—yes, aspirin. “The idea is to gradually induce tolerance with increasing doses of aspirin over a couple of days, while the patient is carefully monitored,” says Dr. Jerschow. “After desensitization, one can be maintained with daily doses of aspirin.”

Barbara started improving within weeks. “I cried my eyes out from relief,” she recalls. “For years, nobody could make heads or tails of my symptoms.”

Elina Jerschow, M.D., center, with Waleed M. Abuzeid, M.B.B.S., and Barbara Roseval.

Next, Barbara’s nasal polyps were removed by Waleed M. Abuzeid, M.B.B.S., an assistant professor of otorhinolaryngology—head & neck surgery at Einstein and director of rhinology and skull-base surgery at Montefiore. Barbara’s sense of smell, which had vanished years earlier, returned. “Oh, how I had missed the smell of bacon and fresh coffee in the morning!” she exclaims.

Unfortunately, some AERD patients don’t respond to desensitization therapy, and many nonresponders get even sicker with treatment. Doctors aren’t sure why, and there’s no way to predict how a patient will react to the therapy.

In 2015, Dr. Jerschow launched a study to learn more about the variations in response to daily aspirin desensitization, focusing on a demographically diverse group of patients in the Bronx. Respiratory symptoms improved in six out of seven of the white non-Latino patients who completed the desensitization program. However, 15 of 20 black and four of 12 Latino patients either didn’t respond to daily aspirin treatment or experienced worseningof their asthma and sinus symptoms.

Delving deeper, Dr. Jerschow looked for blood markers that could help clinicians distinguish the study’s responders from nonresponders. She found that patients tended to respond better to aspirin treatment if they had higher blood levels of 15-HETE (a naturally occurring chemical involved in inflammation) before therapy and lower levels of eosinophils (inflammation-causing white blood cells often associated with asthma) during therapy.

“It would be premature for physicians to use these measures to predict outcomes,” says Dr. Jerschow. “The findings need to be replicated in a larger patient sample, and a test for 15-HETE is not commercially available.”

Barbara took part in the study and is ever grateful she had a good outcome. “Everything is under control,” she says, two years after her first visits with Drs. Jerschow and Abuzeid. “I got my life back because of them.”

In 2007, an expert panel under the auspices of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a revised set of guidelines “to help clinicians provide quality care to people who have asthma.” Studies indicate that routine use of those guidelines could reduce complications in asthma patients by 70 percent—and translate into 44 percent fewer hospital admissions and 80 percent fewer asthma deaths.

Yet surveys of patients and providers and reviews of medical records show that the asthma-care guidelines are not consistently applied. Providers cite a variety of reasons for not adhering, notably a lack of time during patient visits and the difficulty of assessing disease severity and whether a patient’s asthma is being adequately controlled—essential steps for prescribing appropriate medical therapy and providing optimal care.

How to persuade clinicians to incorporate those asthma-care guidelines into routine care? One answer, according to Marina Reznik, M.D., an associate professor of pediatrics at Einstein and an attending physician at Children’s Hospital at Montefiore (CHAM), is to give caregivers an electronic nudge. “Every patient encounter begins with the electronic health record, so why not harness this tool to encourage the best practices?” she says.

Dr. Reznik is spearheading a randomized controlled clinical trial in which Montefiore’s electronic health record system, known as EPIC, prompts nurses to ask patients and their parents a structured series of questions about asthma that address everything from symptoms to medication use to exercise limitations.

“At the time of the visit, an algorithm using the nurses’ collected answers alerts the doctor whether the patient has persistent or uncontrolled asthma,” says Dr. Reznik. “EPIC will then guide providers on steps to take for managing the disease.” Families will also receive educational materials and referrals for help in dealing with environmental triggers in the home, all through EPIC. “It’s one-stop shopping for asthma care,” she adds.

The idea is not completely new. An earlier test improved short-term asthma care by sending physicians a printout reminding them about guideline-based care.

The current trial will evaluate whether giving physicians even more support and guidance through EPIC will sustain their adherence to guidelines, and whether their better adherence, coupled with enhanced interventions aimed at children and caregivers, will improve long-term asthma control. The enhanced interventions include employing outreach workers to support the sickest children by coordinating their care; providing education for caregivers to make sure they follow through on providers’ recommendations; and offering prompts reminding caregivers to discuss issues or questions about their children’s asthma during their next visits.

“The goal is to elicit an in-depth conversation between providers and the families of patients so we can manage children’s asthma more effectively and curb inconsistencies in care,” says Dr. Reznik.

The trial is supported by a five-year, $4.2 million grant from the NIH and will gradually be rolled out to 20 Bronx clinics serving more than 5,000 children who have persistent or uncontrolled asthma. Half the clinics will use the asthma intervention, with the other half serving as controls.

Marina Reznik, M.D., works with a young patient at the Monte ore Asthma Center.

Marina Reznik, M.D., works with a young patient at the Monte ore Asthma Center.

Doctors aren’t the only ones who have room for improvement when it comes to asthma care; many patients don’t comply with recommended treatment. “Fully half of all asthma sufferers fail to follow their doctors’ advice, putting themselves at high risk for serious, even deadly, complications,” says Sunit Jariwala, M.D., an associate professor of medicine at Einstein and the lead adult allergist/immunologist at the Montefiore Asthma Center.

In an effort to convince patients to stick with guideline-based recommendations, Dr. Jariwala and his colleagues have devised a technological fix: an interactive and personalized smartphone app that combines asthma education with games that challenge the user’s asthma knowledge and encourage healthier behaviors.

“We’ve ‘gamified’ asthma management,” says Dr. Jariwala. “We wanted to make the app engaging and fun. That’s the key to sustaining its use and, more importantly, empowering patients to gain control of their disease.”

The app, called ASTHMAXcel, gives patients an ever-present virtual assistant to teach them about asthma, including when and how to use their asthma control and rescue medications and how to minimize exposure to possible triggers. A future version of the app will include personalized text messages.

The app is based on a similar approach used at the Montefiore Asthma Center, where a nurse educator helps people handle asthma’s day-to-day challenges. Such hands-on care has proven successful in reducing asthma-related hospitalizations and ER visits among both children and adults with uncontrolled asthma.

“Since we can’t be there to help patients 24/7, the ASTHMAXcel app extends our reach,” says Dr. Jariwala. “It also makes this type of education and support available to patients and providers who don’t have access to a specialized asthma center.”

A pilot test found that 50 adults who used the app (available for both Android and iOS phones) increased their asthma knowledge and achieved better asthma control and quality of life. An ongoing study is assessing those outcomes in children with asthma.

Sunit Jariwala, M.D.

Sunit Jariwala, M.D.

The ASTHMAXcel app, developed by Dr. Jariwala.

The ASTHMAXcel app, developed by Dr. Jariwala.

Patients’ most serious noncompliance “sin” may be their failure to recognize the warnings signs of an asthma attack—the critical time when a rescue inhaler can prevent a bad situation from getting worse. It may seem baffling that people overlook wheezing or shortness of breath, but everyone tolerates such problems differently.

“Some asthmatics get used to breathing a certain way,” says Jonathan Feldman, Ph.D., an associate professor of pediatrics at Einstein. “Over time, their threshold changes and they simply don’t recognize their airways are restricted. Their perception is off.”

One solution, he says, is for patients to use peak-flow meters—handheld devices that measure the ability to expel air, expressed as peak expiratory flow, or PEF. The meters provide people with instant and objective feedback about whether they need to reach for their inhalers.

For a recent study of children with asthma, Dr. Feldman enrolled Puerto Rican and African American children, who have higher rates of asthma-related complications than all other racial and ethnic groups. Half the children were trained to guess their PEFs just before taking a PEF reading, while the other half simply guessed their PEFs but didn’t get feedback from meters.

After six weeks, children trained to guess their PEFs just before taking PEF readings underperceived their asthma symptoms a mere15 percent of the time, compared with a 42 percent underperception rate for children who guessed their PEFs but didn’t get feedback from meters. By the end of the study, children who saw their PEFs on meters were almost twice as likely to be taking medications for controlling their asthma compared with children who did not see their PEFs.

Now, in a follow-up study funded by the NIH, Dr. Feldman is testing whether peak-flow meters plus brief behavioral interventions can help adolescents with asthma (ages 10 to 17) perceive and control their asthma symptoms over the course of a year. Participants use programmable peak-flow meters that will periodically prompt users to predict their PEFs before measuring them with the meters. Ideally, the peak-flow meters will train children to recognize episodes of airway restriction on their own. “We’ve turned it into a game to make it more appealing to adolescents,” says the researcher. As part of the study, the family reviews the child’s performance with an asthma coach and the child receives individual counseling.

“The counseling will focus on those times when kids underperceive their symptoms,” says Dr. Feldman. “These are teaching moments where we can help children connect symptoms and asthma triggers to peak flow.”

“We have these fantastic medications for asthma,” says Dr. Feldman, “but if the kids don’t use them, they’re meaningless.”

A young asthma patient receives instructions on how to use a peak- ow meter.

A young asthma patient receives instructions on how to use a peak- ow meter.

Allergy shots gradually desensitize patients to allergens such as pollen and dust mites and have been used to treat allergy and asthma sufferers for nearly a century. Studies show that the shots (also known as allergy immunotherapy) can reduce asthma symptoms by as much as 30 percent.

Until a few years ago, doctors recommended restricting allergy shots to patients ages 5 and above. In 2013, revised guidelines were issued that abolished age restrictions.

“In a way, the change made sense,” says Gabriele de Vos, M.D., an associate professor of medicine at Einstein and an attending physician in pediatric and adult allergy at Jacobi Medical Center. “Allergy shots have such a long track record for safety and efficacy, and there was reason to believe that allergy shots might help prevent asthma in very young children. But there was no strong research to support the changes to the guidelines.”

In fact, no one had ever done a scientifically rigorous study of allergy immunotherapy for the youngest asthma sufferers, largely because of the difficulty of giving regular injections to small children. Dr. de Vos decided the matter was too important to leave to chance, so she launched a randomized controlled trial of immunotherapy for preschoolers with asthma. It focused on allergic children who live in cities, who tend to have persistent or uncontrolled asthma and would stand to benefit the most from treatment.

“There was a big hope that the shots would prove effective and lead to a decrease in ER visits and hospitalizations,” she says. “It turned out that the shots were safe for young kids with asthma, but our preliminary analysis has found very little effect on their symptoms or disease outcomes.”

Dr. de Vos suspects that asthma symptoms at young ages may result primarily from viral infections and other nonallergic factors such as air pollution—conditions that allergy immunotherapy wouldn’t help. In addition, children in cities like New York are often sensitive to allergens such as cockroach particles, and those high-dose chronic exposures may be too much for allergy shots to handle. “We know from older children and adults that allergy shots work best against things we’re intermittently exposed to in small amounts,”she says.

“So I wouldn’t necessarily reverse the guidelines,” Dr. de Vos concludes, “but they may need to be refined. Determining who will benefit the most from allergy shots will allow for a more personalized approach to therapy.”

A mother obtains care for her young child.

A mother obtains care for her young child.

Obesity is now recognized as an important cause of asthma. A 2007 study in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine calculated that overweight or obese adults increase their risk of developing asthma by 50 percent. Compared with their lean counterparts, obese asthmatics also tend to have worse asthma control, a higher rate of asthma-related hospitalizations and longer hospital stays.

Studies suggest that in obese adults, mechanical pressure from excess body fat itself can cause asthma by hampering the lungs’ ability to stretch and expand and by reducing lung capacity. In addition, fat tissue synthesizes and secretes high levels of inflammation-causing cytokines, small proteins that may chronically inflame the bronchial tubes. But it’s much less clear why obese children face an increased risk for asthma.

One of the few researchers studying how childhood obesity and asthma are connected is Deepa Rastogi, M.B.B.S., an associate professor of pediatrics and the Joseph S. Blume Faculty Scholar in Pediatric Development at Einstein and director of the Pediatric Asthma Center at CHAM.

“Classic” childhood asthma is mainly allergic asthma: Immune cells known as type 2 helper T cells respond to dust mites or other allergens by secreting well-characterized pro-inflammatory chemicals (interleukins 4, 5 and 13) that inflame the airways. Dr. Rastogi suspected that obesity-associated childhood asthma is driven by an immune response that is not connected to allergies. To find out, she recruited 120 Bronx children ages 7 to 11 and grouped them into four categories of 30 children each: obese asthmatics, nonobese kids with “allergic” asthma, obese nonasthmatics and a control group of nonobese, nonasthmatic children.

In a 2012 paper in Chest, Dr. Rastogi reported that asthma in obese children does indeed occur through an immune response distinct from what occurs in “classic” childhood asthma. It features type 1 helper T cells that release inflammatory chemicals entirely different from those released by the type 2 helper T cells of allergic asthma. A follow-up study by Dr. Rastogi showed that this unusual immune response persists in adolescents and is driven by insulin resistance, a common consequence of obesity.

These and other discoveries from Dr. Rastogi’s lab point to a web of environmental and genetic factors that conspire to cause asthma in obese children. A five-year, $898,000 grant from the NIH is helping her untangle that web. She reported in early 2017 that obese asthmatic children have abnormally active genes in a signaling pathway involving CDC42, a protein that helps activate T cells. The finding reveals new targets for therapy for this fast-growing sub- group of asthmatics, who account for half the cases seen at the Montefiore Asthma Center.

“Ideally, we’ll want to intervene early with these kids, before obesity and asthma set in,” says Dr. Rastogi. “We know that obese mothers tend to have obese children, suggesting that genetic predisposition or children’s environments—or both—may play a role. We can’t change peoples’ genes at this time, but we can change factors that contribute to obesity, such as poor eating habits and lack of exercise.”

Deepa Rastogi, M.B.B.S., studies the connections between childhood obesity and asthma.

Deepa Rastogi, M.B.B.S., studies the connections between childhood obesity and asthma.

Even though pediatricians recommend exercise for nearly every kid with asthma, many young asthma sufferers can be found sitting on the sidelines during gym class or on the playground, particularly in urban areas.

“Some don’t like to exercise, especially if their condition is not well controlled,” says Dr. Reznik. “Also, many parents and school officials mistakenly believe it’s not safe for these kids to exercise. But in many urban areas, there aren’t enough places for kids to exercise outside of school.”

Dr. Reznik has responded with an elementary school–based program that raises asthma awareness and encourages all children, asthmatics included, to be more active. The program is based on CHAM JAM (Children’s Hospital at Montefiore Joining Academics and Movement)—a mix of brief bursts of in-class exercise and lessons on math and geography, guided by an audio CD. CHAM JAM is an initiative of Montefiore’s School Health Program, the largest and most comprehensive school-based health program in the country.

A test of CHAM JAM in four Bronx schools (in which two received the intervention and two served as controls) found that performing the in-class intervention up to three times a day significantly increased children’s activity levels. Teachers also reported that students focused better on their lessons afterward and that many kids took the CDs home to do the exercises with their families.

Now Dr. Reznik is expanding CHAM JAM with a special emphasis on asthma. Along with the exercise component, the intervention will include an asthma awareness week, featuring a school-wide assembly and opportunities for kids to make drawings and compose poems and raps related to asthma. “All students are included, which we hope will create a more supportive school environment and reduce any stigma associated with the disease,” she says. There will also be efforts to educate school personnel to ensure that kids with asthma are getting proper care and have parental permission forms on file so school nurses can administer medications.

“There’s only so much we can do for these children in a clinical setting,” says Dr. Reznik. “We need to get out into the community and overcome barriers to proper asthma care at

every level.”

A central tenet of asthma care is that it’s nearly impossible to keep asthmatics healthy if their homes aren’t healthy, too—as free as possible from mold, cockroaches, dust mites and other potential asthma triggers. That’s especially hard in the Bronx, where more than 80 percent of residents are renters, with little control over environmental triggers. Asthma specialists at Einstein and Montefiore have responded to this problem by taking part in several programs focused on both health and housing.

One example is the Bronx Healthy Buildings Program. For the past two years it has worked to improve indoor air quality and energy efficiency in substandard housing by inspecting buildings and fixing those needing repair.

The program—a joint project of Montefiore, the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and other local partners—also hires and trains tenant leaders to serve as community health workers who teach other tenants about asthma self-management. When the program ends in 2018, the team will evaluate its impact on tenant health and medical expenditures, says Dr. Reznik, the principal investigator at Montefiore.

Asthma and substandard homes plague nearly every region of the Bronx, making it difficult for health and housing advocates to know where to apply limited resources. That’s where population health specialists such as Amanda Parsons, M.D., M.B.A., enter the picture. Dr. Parsons, an assistant professor of family and social medicine at Einstein and vice president of community & population health at Montefiore, uses data to design and carry out programs to improve the health of the community.

One of Dr. Parsons’ colleagues—Colin Rehm, Ph.D., an assistant professor of epidemiology & population health—specializes in data mining, the art and science of finding hidden trends in gigabits of information. In a recent project, Dr. Rehm sorted through Montefiore’s patient data to identify neighborhoods with unusually high rates of diabetes, hypertension or obesity. Dr. Parsons’ team then worked with local bodegas to sell more fruits, vegetables and sparkling water, and fewer sugar-laden snacks and sodas.

The team has now begun using the same data-mining approach for asthma. Its first project found that Eastchester Gardens, a large public housing complex in the Williamsbridge section of the Bronx, has one of the borough’s largest concentrations of asthma sufferers—particularly people with uncontrolled disease. Working with the tenants’ association and the Bronx Community Health Network, team member Elizabeth Spurrell-Huss, L.C.S.W., M.P.H., a community & population health senior project manager at Montefiore, organized a community health event called “Breathe Easy,” in which residents could consult with clinicians about asthma management and with pest-management experts about household cleanup.

“Public and private insurers won’t pay for mold removal or pest control, but they will pay for emergency room visits and hospitalizations that directly result from those triggers—which is frustrating,” says Dr. Parsons.

Both medical education and clinical care increasingly recognize that social, economic and environmental conditions strongly affect people’s health—something that Dr. Parsons and her Montefiore colleagues have realized for quite some time.

“A hospital system cannot think just about providing treatment but must instead think about providing the community with the tools it needs to be healthy,” says Dr. Parsons. “We’ve made a conscious effort over the past few years to move from health fairs, which tend to focus on health screenings and community relations, to more-targeted community interventions. The idea is to take evidence-based prevention practices and adapt them to specific places and cultures.”