Einstein researchers report that the composition of people’s gut bacteria may explain why some of them suffer life-threatening reactions after taking a drug for treating colorectal cancer. The findings, described last November in npj Biofilms and Microbiomes, a Nature research journal, could help predict which patients will suffer side effects—and may prevent complications in susceptible patients.

“We’ve known that people’s genetic makeup can affect how they respond to a drug,” says study leader Libusha Kelly, Ph.D., assistant professor of systems & computational biology and of microbiology & immunology at Einstein. “Now it’s becoming clear that variations in one’s gut microbiome—the population of bacteria and other microbes that live in the digestive tract—can also influence the effects of treatment.”

Irinotecan is one of three first-line chemotherapy drugs used to treat colorectal cancer that has spread, or metastasized, to other parts of the body. However, up to 40 percent of patients who receive irinotecan experience severe diarrhea that can lead to death.

Irinotecan is administered intravenously in an inactive form. Liver enzymes metabolize the drug into an active, toxic form that kills cancer cells. Later, other liver enzymes convert the drug back into its inactive form, which enters the intestine via bile for elimination. But some people harbor digestive-tract bacteria that use part of inactivated irinotecan as a food source by digesting the drug with beta-glucuronidase enzymes. Unfortunately, this enzyme action metabolizes and reactivates irinotecan back into its toxic form, which causes serious side effects by damaging the intestinal lining.

Dr. Kelly and her colleagues investigated whether the composition of a person’s microbiome influenced whether irinotecan would be reactivated or not. The researchers collected fecal samples from 20 healthy individuals and treated the samples with inactivated irinotecan. Then using metabolomics (the study of the unique chemical fingerprints that cellular processes leave behind), the researchers grouped the fecal samples according to whether they could metabolize, or reactivate, the drug. Four of the 20 individuals were found to be “high metabolizers” and the remaining 16 were “low metabolizers.”

Fecal samples in both groups were analyzed for differences in the composition of their microbiomes, focusing on the presence of beta-glucuronidases. The researchers found that the microbiomes of high metabolizers contained significantly higher levels of three previously unreported types of beta-glucuronidases compared with low metabolizers.

The findings suggest that analyzing the composition of patients’ microbiomes before giving irinotecan might predict whether patients will suffer side effects from the drug.

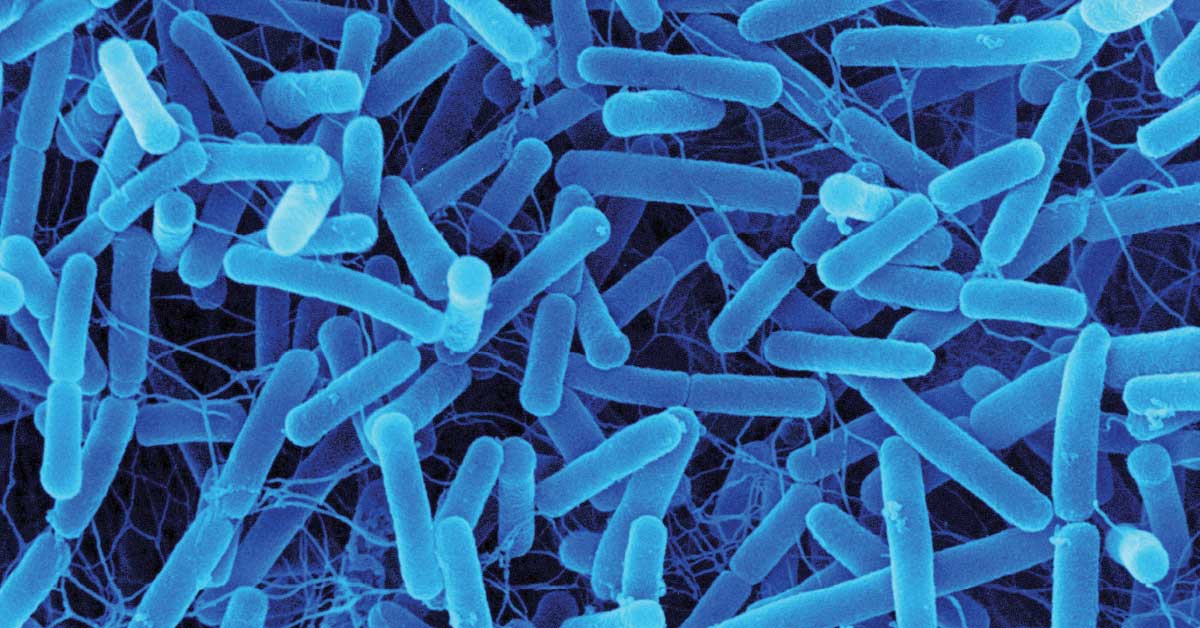

Scanning electron micrograph of Proteus, rod-shaped bacteria commonly found in the intestine.

Scanning electron micrograph of Proteus, rod-shaped bacteria commonly found in the intestine.