Error: No layouts found

Last summer, for the first time ever, the U.S. Surgeon General sent a letter to every physician in the country. The subject wasn’t heart disease or cancer, or even the Zika virus menace. It was America’s opioid epidemic.

“Since 1999, opioid overdose deaths have quadrupled and opioid prescriptions have increased markedly—almost enough for every adult in America to have a bottle of pills,” wrote Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy, M.D., M.B.A. “Yet the amount of pain reported by Americans has not changed. Now, nearly two million people in America have a prescription opioid use disorder, contributing to increased heroin use and the spread of HIV and hepatitis C.”

Many experts trace the roots of today’s opioid epidemic to the Vietnam War, from which thousands of soldiers returned addicted to heroin. So the government cracked down on opioids, both legal and illegal. Research in the late 1980s indicated that patients with chronic pain were suffering unnecessarily and could benefit from newly formulated prescription opioids that seemed to pose little risk of addiction or abuse.

“When I was in medical school some 15 years ago, we were taught to aggressively treat people with pain,” says addiction medicine specialist Joanna L. Starrels, M.D., M.S., who is an associate professor of medicine at Einstein and an attending physician in general internal medicine at Montefiore. “The message was, ‘Be supportive of your patients and don’t worry about addiction.’”

The conclusions drawn regarding the addiction potential of prescription opioids turned out to be deeply flawed. But it was too late. America was already hooked.

Julia H. Arnsten, M.D., M.P.H., directs clinical, research and training programs in addiction medicine.

“It’s so rare to see a cause of death increase in the U.S.,” said former Centers for Disease Control and Prevention director Thomas R. Frieden, M.D., last December. “Since 2000, more than 300,000 people have died of opiates, and we have yet to see big decreases anywhere.” (See the “Deadly Opioid Statistics” sidebar on page 32 for highlights from a CDC report issued that month.) Also in December, a survey released by the Washington Post−Kaiser Family Foundation found that one-third of Americans who have taken prescription opioids for at least two months report becoming addicted to or physically dependent on the painkillers.

While physicians around the country now scramble to prevent and treat opioid misuse, at least one region was prepared: the Bronx. “Opioid dependence and related deaths have been high in the Bronx for decades and are now even higher,” says Julia H. Arnsten, M.D., M.P.H., a professor of medicine, of epidemiology & population health and of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Einstein and chief of the Einstein-Montefiore division of general internal medicine in the department of medicine. “Sadly, the rest of the country is now catching up.”

With Dr. Arnsten in the lead, Montefiore has established one of the nation’s foremost clinical, research and training programs in addiction medicine. Its key elements are highlighted below.

Dr. Arnsten, center, discusses a seriously ill patient (addiction, hepatitis C and psychiatric illness) with, from left, colleagues Aaron D. Fox, M.D., M.S.; Joanna L. Starrels, M.D., M.S.; Brianna L. Norton, D.O., M.P.H.; Chinazo O. Cunningham, M.D., M.S.; and Shadi Nahvi, M.D., M.S.

Double trouble: Opioid misuse and HIV infection

Since HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) was introduced in the mid-1990s for treating HIV infection, most but not all patients have readily embraced these lifesaving medications. Among the holdouts were patients struggling with opioid misuse. Their addiction makes it difficult to follow doctors’ orders or discourages them from seeking healthcare in the first place.

Dr. Arnsten was among the first researchers to study how best to care for this doubly marginalized population of opioid-addicted, HIV-positive people. She found the solution in the tuberculosis field, where clinicians discovered they could cure patients by directly handing them their medications day after day. In 2004, Dr. Arnsten brought this approach—called “directly observed therapy” (DOT)—to substance abuse clinics.

Dr. Starrels studies opioid use in patients with HIV.

“People with opioid addictions tend to avoid any contact with the healthcare system but do visit clinics for their regular doses of methadone,” she says. “So, the idea was that when they came in, we’d also give them antiretrovirals to make sure they received proper HIV care.” This novel use of DOT proved successful, significantly reducing the viral loads of HIV-positive methadone users and increasing their counts of CD4 immune cells. Dr. Arnsten’s study showed that chronic medical care could be effectively integrated into substance abuse care, which had previously focused solely on addiction.

Dr. Arnsten has also urged the healthcare community to integrate substance abuse treatment into conventional clinical practice.

“Primary care providers can be reluctant to tackle opioid abuse,” she says. “They’re worried they’ll attract patients who will be disruptive and demanding and unpredictable. But substance abusers are already in their practices. The patients are just not telling their doctors about their addictions—and not getting treatment. Such care doesn’t need to be offered in a separate setting. That’s an important message for states that have few resources for dealing with the growing problem of substance abuse.”

Dr. Arnsten’s most important contribution to addiction medicine may be a training program she developed at Montefiore. She realized early in her career that she’d need help from other experts in her field. But addiction medicine specialists were few and far between, not just at Montefiore but around the nation. The solution, she realized, was to develop her own local specialists—a goal she realized through a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant that she won in 2002.

The NIH grant allowed Dr. Arnsten to create the first-of-its-kind Clinical Addiction Research and Education (CARE) program, based at Montefiore. CARE includes two components: a two-year fellowship that prepares physicians to conduct research and deliver clinical care in addiction medicine, culminating in a master’s degree issued by Einstein; and an inpatient and outpatient training program in substance abuse diagnosis and treatment for residents in internal medicine, family medicine and psychiatry. Thus far, about 15 fellows have trained under CARE, many of whom have remained at Montefiore and launched their own NIH-funded studies. In addition, some 600 residents have rotated through the program, expanding the ranks of addiction medicine specialists nationwide.

Mitigating prescription opioid abuse

Dr. Starrels, one of Dr. Arnsten’s protégés, started her research career a decade ago by studying how primary care providers were prescribing opioids for chronic pain. At the time, prescription opioid misuse was a relatively minor problem, but a looming epidemic was evident to those who bothered looking.

Providers were “pretty lax” in prescribing these drugs, Dr. Starrels found. “Few doctors were monitoring patients for opioid misuse. They based their suspicions on patient characteristics such as race rather than on actual risk factors, such as a personal or family history of addiction or mental health problems.”

Next, Dr. Starrels used an NIH career development award to study tools for reducing opioid addiction and overdose in treating chronic pain. One such tool—the opioid treatment agreement (OTA) between doctor and patient—defines treatment and monitoring plans and conditions for terminating opioid use. She concluded that OTAs should be used from the beginning with all patients rather than waiting until things go wrong. Her study of urine drug testing for patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain found that interpreting the results is more complicated than many physicians realize.

Today, Dr. Starrels is examining prescription opioid use in patients with HIV. Now that they are living longer, people with HIV are experiencing painful problems associated with aging, such as osteoarthritis. Unfortunately, antiviral therapy can worsen their misery by causing peripheral neuropathy (damage to nerves in the feet and lower legs). Opioids are commonly prescribed to alleviate their chronic neuropathy pain.

“We know that patients using illicit drugs such as heroin are less likely to adhere to HIV treatment,” says Dr. Starrels, who served as a core expert for the CDC 2016 opioid prescribing guidelines. “We don’t know if taking prescription opioids similarly interferes with HIV therapy. If it does, then we have to pay more attention to how we prescribe opioid drugs to people with HIV and how we monitor people with HIV for misuse.”

In an NIH-funded study, Dr. Starrels will follow 250 individuals with HIV and chronic pain, including patients who use prescription opioids (intermittently and long-term), those who don’t use these drugs at all and those with and without a history of opioid misuse.

“Like all primary care physicians, HIV providers are overburdened,” Dr. Starrels acknowledges. “We often don’t have the time, the resources or the training to perform the long laundry list of things for ensuring that these medications are used safely. But given what we now know about the risks of these medications, it would be reckless to continue prescribing opioids the way we’ve been doing.”

Supporting people on society’s margins

After two decades on the front lines of the Bronx opioid wars, Chinazo O. Cunningham, M.D., M.S., a professor of medicine and of family and social medicine at Einstein and associate chief of the division of general internal medicine at Montefiore, has mixed feelings about the new concern over drug addiction.

Dr. Cunningham has championed buprenorphine as an alternative to methadone.

“Now, with addiction spreading from cities to rural and suburban areas, from the poor to the affluent and from minorities to whites, the outcry is loud,” she wrote in an April 2016 post on The Doctor’s Tablet, an Einstein blog. “Suddenly, we must do more. . . . It’s about time that we finally recognize that drug addiction is a medical problem that requires medical treatment, not punishment. It is unfortunate that our path to this realization has been so bittersweet—and so long in coming.”

The medical treatment for addiction to heroin and prescription pain relievers has relied mainly on methadone—a less-addictive opioid, used for decades, that doesn’t produce the “high” that others do. Taking methadone as maintenance therapy reduces people’s use of drugs they’ve been misusing as well as their craving for those drugs. But since the early days of her career, Dr. Cunningham has championed the use of a methadone alternative called buprenorphine, introduced in 2002.

Like methadone, the opioid buprenorphine blocks cravings for other opioids and helps relieve pain. But according to Dr. Cunningham, buprenorphine carries a lower risk of overdose than methadone, making it appropriate for office- and community-based treatment. Fears of misuse, however, have limited its availability.

Illicit use of buprenorphine occurs, Dr. Cunningham acknowledges, mainly because the drug is difficult to obtain legally. And those using buprenorphine illicitly are self-treating their withdrawal symptoms or addiction rather than taking it to get high, she says.

Convinced of buprenorphine’s value, Dr. Cunningham began developing and testing new ways to expand the drug’s use to nonmedical settings such as syringe-exchange programs. This approach, she has found, improves people’s access to opioid addiction treatment, enhances health outcomes and reduces behaviors that spread HIV infection among injection drug users. She has also shown that buprenorphine is safe and effective when delivered in primary care settings, even by physicians with little training in addiction medicine.

“The science is clear: medication-assisted treatment with an opioid agonist—like buprenorphine—is the most effective treatment available for opioid addiction,” Dr. Cunningham wrote in a Huffington Post blog.

Thanks in part to her efforts, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the American Society of Addiction Medicine have recently amended their buprenorphine treatment guidelines to expand the drug’s availability.

Dr. Cunningham’s latest project: developing a “live” database of all prescription opioid use within the Montefiore system, with the goal of more fully understanding how these drugs are used, how clinicians can prevent opioid misuse and how opioid use is related to clinical outcomes.

“One challenge in tackling these issues is that the field is fractured,” says the researcher, whose work is supported by an NIH midcareer investigator award. “Addiction treatment historically has been what psychiatrists do. And then there’s pain management, which is what primary care doctors and some subspecialists do. There’s been little communication between those who prescribe these medicines and those who must deal with the unintended consequences. This database will provide a foundation for better understanding what the problems are and how we can address them.”

Dr. Cunningham is also using the NIH award to develop a standardized approach to mentoring junior investigators in addiction medicine, with a focus on minorities and women, who have been underrepresented in the field.

Breaking the cycle of drug use and incarceration

One might imagine that incarceration would help opioid users, forcing them to kick their habit by going “cold turkey.” But that’s wishful thinking, addiction medicine specialists say. Studies show that up to 75 percent of people with opioid addictions relapse within three months of release, increasing the likelihood they’ll find themselves back behind bars. Compounding the problem: Few prisons provide addiction treatment, and newly released inmates often shun health services of any kind.

How to break the cycle of drug use and incarceration?

One possible solution, devised by Aaron D. Fox, M.D, M.S., an associate professor of medicine at Einstein, is to reach out to ex-inmates before the ink on their release papers is dry. Studies show that drug users are at highest risk of relapse and deadly overdose in the two weeks immediately after release.

Dr. Fox, a CARE alumnus, first looked at the problem from the inmates’ perspective. Through lengthy interviews soon after prison release, he learned that forced abstinence from drugs in prison may turn former inmates against subsequent treatment with methadone or buprenorphine.

Dr. Fox works with Einstein medical student Adam Chamberlain to reduce opioid misuse among formerly incarcerated individuals.

“Individuals who’d been taking methadone or buprenorphine in the community could no longer take those medications in prison—causing them to experience painful withdrawal,” says Dr. Fox. “Now that they’re out of prison, these former inmates don’t want to go back on those medications for fear of having to go through withdrawal again should they miss a dose or be reincarcerated.” He reported his findings last year in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment.

Many former inmates felt that entering treatment would be a step backward or a sign of failure, reflecting the social stigma often associated with substance abuse care. Others didn’t know that buprenorphine can be dispensed for take-home use, sparing them the stigma and inconvenience of regular substance abuse clinic visits. And many drug users said that since they hadn’t misused drugs for months, they had no need for maintenance medications on release from prison. “Basically, there was a lot of confusion about drug treatment in general and buprenorphine use in particular,” he says.

Dr. Fox’s interviews led him to recommend using peer mentors—formerly incarcerated drug users who have used buprenorphine—to broach the idea of drug treatment with newly released inmates.

“The hope is that the mentors can dispel some of the myths about treatment, help these individuals navigate the healthcare system and get them into our clinic for care,” says Dr. Fox, who is co-director of the Bronx Transitions Clinic, a collaboration between Montefiore and the Osborne Association, a community-based organization that provides reentry services and outpatient drug treatment to former inmates.

“Ideally,” says Dr. Fox, “we would want the mentors to meet people right at the prison door. We’re also looking into ways to get information to inmates about the program while they’re still inside.”

His intervention strategy, called Buprenorphine Facilitated Access and Supportive Treatment (BUP-FAST), will be tested in an NIH-funded study of 72 newly released inmates who’ll be randomly assigned to receive intensive peer mentoring or a simple referral to a substance abuse clinic.

“The primary goal of BUP-FAST is to get people to show up for treatment,” says Dr. Fox. “But we’ll also look at whether we can reduce the rates of relapse, overdose, recidivism and reincarceration.”

Deadly Opioid Statistics

Last December, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a sobering report on deaths due to America’s opioid epidemic (“Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths—United States, 2000–2014”). Among the findings:

From 2000 through 2014, the death rate from drug overdoses in the United States increased by about 140 percent. In addition, the 2000 through 2014 period saw a…

increase in the rate of overdose deaths involving opioids (opioid pain relievers and heroin).

47,000+

Heroin overdose deaths more than tripled between 2010 and 2014, driven mainly by large increases in heroin use across the country due to the drug’s increased availability, high purity and relatively low price compared with diverted prescription opioids.

Addiction to opioids and cigarettes

Opioid misuse is clearly bad for your health. But surprisingly, cigarettes pose an even greater health threat to people who misuse drugs.

“Of the patients we see in our opioid treatment programs, up to three-quarters of them are dying from smoking-related illnesses, such as pneumonia, heart disease and cancer,” says Shadi Nahvi, M.D., M.S., an associate professor of medicine and of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Einstein and an attending physician in internal medicine at Montefiore. In a 2006 survey, Montefiore researchers found that 83 percent of patients in its substance abuse clinics were current smokers—five times the rate in the overall New York City population. Researchers have found many reasons why opioid use and smoking are so intertwined. Some evidence suggests that nicotine triggers the same reward centers in the brain as opioids, so substance abusers may simply be balancing one addiction with another. Social factors, such as hanging out with peers who smoke, probably also encourage people to light up.

Dr. Nahvi talks to a patient.

While the majority of people who misuse opioids smoke, most of them would like to shake the habit. Nearly half of the smokers in the Montefiore survey were thinking about quitting in the next six months, and an additional 22 percent were immediately ready to quit (within the next month) and had made a serious attempt to quit within the previous month.

Drug abuse treatment programs traditionally ignore smoking, assuming that smoking cessation efforts might jeopardize drug treatment and that patients have little interest in quitting.

Dr. Nahvi is having none of that. Several years ago, she tested whether varenicline (Chantix), a prescription drug that reduces cravings and decreases the pleasurable effects of tobacco products, might help reduce cigarette use among opioid-dependent smokers. It stood to reason that varenicline—the most effective stand-alone smoking cessation drug—would work well in this population, but no one knew for certain. “The original trials that led to the drug’s approval by the FDA excluded people with substance use disorders,” says Dr. Nahvi, another CARE alumna.

Her study found that about 10 percent of the patients who took varenicline were able to quit, compared to none of the controls receiving a placebo. The results were promising, but the 10 percent quit rate fell far below varenicline’s 40 percent success rate in the general population.

Dr. Nahvi suspected that treatment adherence might be an issue and launched a follow-up study taking advantage of the clinics’ robust patient support infrastructure. “We wanted to see if adding short-term adherence support—essentially handing people their doses of varenicline several times a week—would help,” she explains. “And it did. The success rate nearly doubled, to 19 percent.”

Dr. Nahvi was recently awarded a five-year, $3.4 million NIH grant to study whether extended adherence support can be even more successful in getting people in opioid treatment programs to stop smoking.

Ending opioid addiction

“I know solving this problem will not be easy,” Surgeon General Murthy concluded in his letter to the nation’s physicians. “We often struggle to balance reducing our patients’ pain with increasing their risk of opioid addiction. But, as clinicians, we have the unique power to help end this epidemic.”

The Surgeon General proposed building “a national movement of clinicians” to accomplish three things:

• educate ourselves to treat pain safely and effectively;

• screen our patients for opioid use disorder and help them obtain evidence-based treatment; and

• shape the public view of addiction by talking about and treating it as a chronic illness, not a moral failure.

“As cynical as times may seem,” he wrote, “the public still looks to our profession for hope during difficult moments. This is one of those times.”

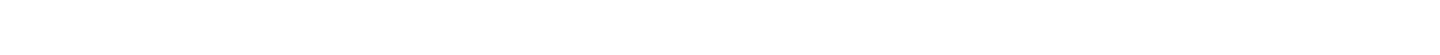

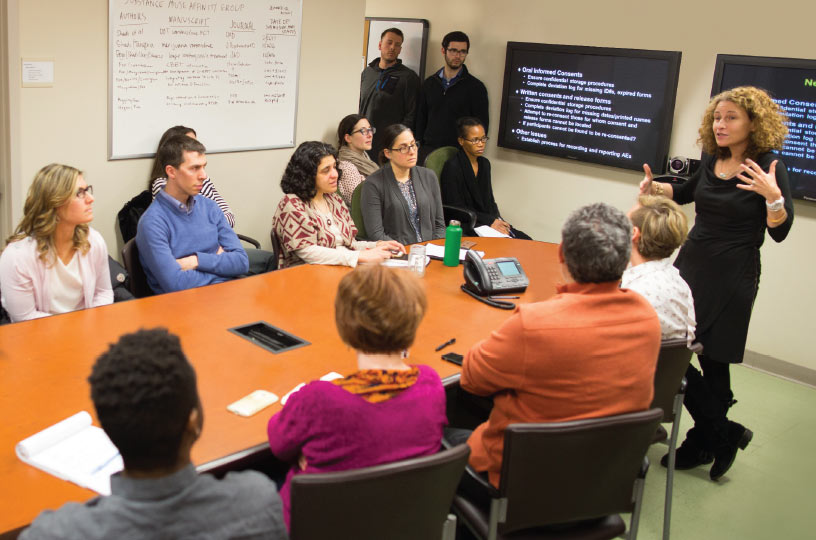

Dr. Arnsten leads a discussion about protecting the confidentiality of patients participating in research projects.