Error: No layouts found

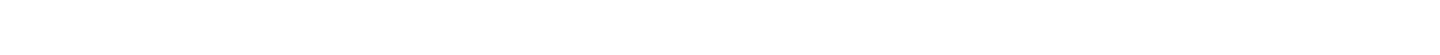

David Shechter, Ph.D., studies what he calls “the biochemistry of epigenetic information,” i.e., non-DNA molecules that influence gene expression, such as methyl groups and the histone proteins that package DNA to form chromatin. Dr. Shechter graduated from Cornell University, earned his Ph.D. from the Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons and did his postdoctoral research at Rockefeller University. He came to Einstein in 2009 and is an associate professor of biochemistry.

David Shechter, Ph.D., right, with third-year graduate student Benjamin Lorton.

Designing experiments is one of my favorite aspects of research. There’s also the thrill of discovery and the joy of having your hypothesis proven wrong.

There’s an Isaac Asimov quote, “The most exciting phrase in science is not ‘Eureka’ but ‘That’s funny…’” Of course I’m always happy when our data support our hypothesis. But getting results inconsistent with your hypothesis—something “funny” and totally unexpected—can lead to a new discovery. When I’m interviewing prospective Ph.D. or M.D./Ph.D. students I tell them, “If you don’t wake up occasionally in the middle of the night thinking about an interpretation for an experiment you’ve done or a new idea for an experiment, then you’re in the wrong field.” Science is a crazy, not-very-lucrative career, and the thrill of discovery is the major reward.

We do several things—I’d get bored doing just one. We study a class of enzymes called protein arginine methyl transferases (PRMTs), which transfer methyl groups onto cellular proteins, including the histones that bind to DNA to form chromatin. Overexpression of PRMTs has been linked to cancer. Our basic biochemistry and research on the frog Xenopus laevis has shown how PRMT-5 can function to cause cellular changes. We’re currently bringing our basic findings in the frog into human cancer studies.

We also study proteins called histone chaperones, which attach to those histone proteins not bound to DNA and escort them throughout the cell. The gene that codes for one of those histone chaperones, Npm1, is the most frequently mutated gene in acute myeloid leukemia, and we’ve gained some unique insights into its function.

In the lab—I love hearing the sounds and seeing people working. People have this idea that scientists are always alone. But people talk all the time in an open lab, so it’s actually a very social job.

There’s a strong collaborative environment here, and my own research has certainly benefited from it.

I really like to cook. In the lab you have to be precise and accurate, but not when you’re cooking. I love going to a restaurant, ordering something interesting and then trying to duplicate it at home. I’m pretty good at it. I also do photography, but my 14-year-old daughter, the oldest of our three kids, decided she wants to be

a wedding photographer and took

my camera.

They all love coming to the lab, although none of them seems interested in a scientific career. But you never know where kids will go. After all, my dad taught social studies and my mother taught art.