Like some other first-time mothers, Cynthia Vasquez of the Bronx experienced problems before and after giving birth, at age 18, to her son Daniel. But Cynthia’s struggles several years ago were especially severe. Six months into her pregnancy, she was afflicted with pain and stiffness in her wrists, knees, ankles, and almost every other joint in her body, and her condition grew progressively worse.

Weeks went by before doctors diagnosed her condition: systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)—a chronic autoimmune disease that inflames and damages tissues and organs throughout the body. SLE is the most common form of lupus. The American College of Rheumatology estimates that SLE affects as many as 322,000 U.S. adults—a conservative estimate, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There is no cure, and treatment can be challenging. Cynthia was prescribed powerful immunosuppressant drugs to relieve the inflammation, but she could barely move by then.

Shortly before giving birth, Cynthia was admitted to Montefiore’s Weiler Hospital, where Irene Blanco, M.D., took over her care. “Little by little we quieted her symptoms,” says Dr. Blanco, associate professor of medicine at Einstein and director of the adult lupus clinic at Montefiore.

Ninety percent of lupus patients are women, most of whom develop the condition in their childbearing years, between ages 15 and 45. Lupus that begins during pregnancy tends to be particularly complicated and challenging to treat. The disease is two to three times more prevalent among women of color—particularly Hispanics, like Cynthia, and African Americans—than among Caucasian women. Minority women tend to develop lupus at a younger age, suffer more-severe complications, and have higher mortality rates than their white counterparts.

Symptoms of lupus include the severe pain and physical impairment that Cynthia experienced, as well as fatigue, hair loss, difficulty thinking, and skin rashes that can be disfiguring. Inflammation from lupus can ravage organs throughout the body, leading to complications involving the kidneys, skin, lungs, and heart.

As better treatment has reduced kidney-related lupus deaths, cardiovascular disease now ranks as the leading cause of early death in people with lupus. Studies show that SLE patients face a heart-attack risk up to 50 times greater than the risk for the general population.

No two lupus patients are alike, and there’s no standard therapy for treating the many manifestations of the disease.

– Dr. Irene Blanco

Early diagnosis of lupus allows doctors to intervene with powerful drugs to halt disease progression and prevent lupus’ notorious inflammation from silently damaging vital organs. Cynthia’s disease was diagnosed within a few weeks of symptom onset, but many young lupus patients aren’t so lucky—mainly because their symptoms imitate those of many other diseases.

Einstein and Montefiore researchers recently reported on nearly 600 pediatric lupus patients who were enrolled in a North American registry before age 21. In a paper published in 2017 in Arthritis Care & Research, the researchers found that only two-thirds of the patients were referred to pediatric rheumatologists within three months of symptom onset, and one of every 10 patients experienced referral delays lasting as long as a year.

Patients living in poverty and in areas without access to specialty care tended to have the longest delays, says lead author Tamar Rubinstein, M.D., assistant professor of pediatrics at Einstein and attending physician in pediatric rheumatology at Children’s Hospital at Montefiore (CHAM). Dr. Rubinstein worries that treatment delays will only get worse, mainly because the pool of pediatric rheumatologists is shrinking. There are only 300 such specialists in the entire country, leaving large swaths of the nation underserved.

CHAM, with its three pediatric rheumatologists and three pediatric rheumatology fellows, is a notable exception to this trend. It has a long history of caring for young lupus patients, reflecting the needs of its large Hispanic and African-American community.

The Lupus Nephritis Clinic opened at CHAM in 2012. As its name implies, the clinic focuses on lupus-related kidney inflammation, a potentially deadly complication. Up to half of all SLE patients and nearly 70 percent of Hispanic and African-American patients with the disease will develop lupus nephritis. Left unchecked, kidney inflammation can cause irreversible kidney scarring, which can result in organ failure.

“End-stage kidney disease is the last thing we want for our patients,” says Beatrice Goilav, M.D., associate professor of pediatrics at Einstein, interim chief of pediatric nephrology at CHAM, and co-director of the Lupus Nephritis Clinic. “It reduces the life expectancy of a child or young adult on dialysis by four decades.” The only alternative is transplantation, which is limited by the availability of donor organs and carries its own risks and complications. That’s the route taken by young pop star Selena Gomez, perhaps the world’s best-known lupus patient, who received a donated kidney in 2017, at age 25.

CHAM’s Lupus Nephritis Clinic offers patients access to every type of specialist they might need in a single visit, including a rheumatologist, nephrologist, dermatologist, social worker, and nutritionist. Clinic staff also tend to the psychosocial aspects of lupus, such as treatment noncompliance.

It’s not uncommon for young patients to take a “drug holiday”—a respite from their demanding medication regimens and the drugs’ sometimes onerous side effects, such as acne and weight gain. “After all, they’re teenagers,” says clinic co-director Dawn Wahezi, M.D., associate professor of pediatrics at Einstein and division chief of pediatric rheumatology at CHAM. “They just want to feel normal.”

But such holidays have a cost: When patients don’t take their meds, the disease often flares. “Then we have to hit them hard with steroids to control the kidney inflammation,” Dr. Goilav says. “The Lupus Nephritis Clinic allows us to follow up with these kids very closely. The more we see them and get to know them, the more things we can do to improve compliance.”

Staff are also on hand to help patients who suffer from central nervous system complications of lupus (CNS lupus), including stroke, depression, anxiety, and “lupus fog,” a constellation of cognitive abnormalities including memory problems and confusion. “These complications aren’t always life threatening, but—like lupus nephritis—they have a profound effect on overall health and quality of life,” Dr. Rubinstein says. Making matters worse, CNS lupus in children is especially difficult to diagnose, leading to treatment delays.

“I was depressed for two years,” Cynthia says. “The medications. The fatigue. Being home all day. Having to watch myself gain weight. It adds up.”

Dr. Rubinstein is now running a multicenter study to find out how best to screen for mental illnesses in children and adolescents with lupus. Her research will also investigate risk factors for CNS lupus and assess how stress and adversity affect lupus outcomes.

At age 21, patients “graduate” from the pediatric lupus clinic to its adult counterpart at Montefiore or to outside caregivers. It’s the first time that many young patients have had to make decisions about their care, arrange doctors’ appointments, fill prescriptions, and file insurance claims—the nitty-gritty of managing a chronic illness.

“It’s a particularly stressful and vulnerable time in their lives, when they are transitioning out of high school and going to college or into the workforce,” Dr. Wahezi says. “It’s also when anxiety and depression tend to peak in lupus.”

Staff begin preparing patients for this transition months and sometimes years in advance. “When the time comes, we do our best to communicate with their new physicians and co-manage the patients for a time,” Dr. Wahezi says. “It’s tough all around. We develop quite a bond with these young patients.”

Cynthia, now 22, hasn’t experienced a major flare-up in many months, but her disease is hardly quiescent. Lately, she’s been dealing with migraines and chest pains (from serositis—the inflammation of the membrane surrounding her heart). Even worse, she has developed signs of lupus nephritis. Like most lupus patients, Cynthia had no idea that her kidneys were faltering. The first indication came from a routine urine test, revealing that her kidneys were having trouble filtering waste from her blood.

“I can’t tell you how frustrating this was for us,” Dr. Blanco says. “We had her on full-dose drugs to prevent nephritis. And she’s a model patient, doing everything right.” Dr. Blanco immediately scheduled Cynthia for a kidney biopsy to confirm the results of the urine test.

Cynthia’s biopsy revealed that her kidneys were inflamed, but fortunately there were few signs of scarring. Around the same time, however, her joint pain returned. Dr. Blanco started her on rituximab (sold as Rituxan or MabThera), a powerful drug used for certain types of autoimmune diseases. “But then she developed an allergy to the drug—part and parcel of managing patients with this disease,” Dr. Blanco says with evident frustration.

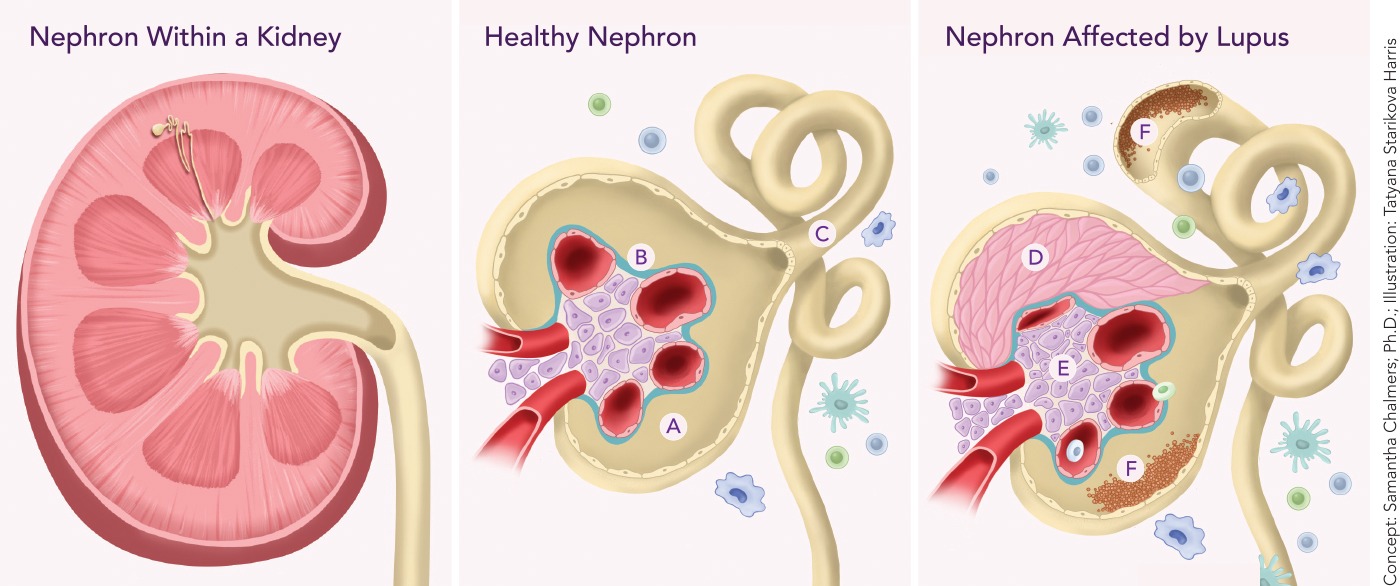

The kidney biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing and staging lupus nephritis. When examining kidney tissue from lupus patients, pathologists have tended to focus on the kidney’s glomeruli, which are clusters of capillaries that filter the blood.

Largely ignored were the tubules—small canals in the kidney that convert the filtered blood into urine. Tubule damage was thought to have little prognostic value, since it was assumed to be a consequence rather than a cause of long-standing lupus nephritis. But after mouse-model studies hinted at the importance of tubule damage in lupus, Einstein-Montefiore researchers assessed tubules in the clinical setting.

It’s tough all around. We develop quite a bond with these young patients.

– Dr. Dawn Wahezi

“When we looked at kidney biopsies from 131 lupus patients with normal or mildly impaired kidney function, we found that many already had severe tubular scarring, which strongly predicted—independent of glomerular damage—that they’d progress to end-stage renal disease in a short time,” says Anna Broder, M.D., M.Sc., associate professor of medicine at Einstein and a rheumatologist at Montefiore. The results were published in 2018 in Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism.

“For some of these patients, tubular damage occurred long before obvious glomerular disease developed,” Dr. Broder says. “So treating early tubular inflammation—the cause of tubular damage—may help prevent end-stage renal disease and improve survival.”

In a study examining kidney biopsies from 203 lupus patients, Dr. Broder and her colleagues found that taking the drug hydroxychloroquine was strongly associated with reduced tubule inflammation. The lead author of that study, published in 2018 in Arthritis & Rheumatology, was Montefiore rheumatology fellow Alejandra Londono Jimenez, M.D. The researchers are planning further studies to confirm hydroxychloroquine’s ability to prevent kidney-tubule damage.

A kidney (above left) contains about 1 million blood-filtering units called nephrons, each with a glomerulus (a cluster of tiny blood vessels) and a tubule (see healthy nephron, center). Blood is filtered by vessels of the glomerulus (A), and the filtrate (the filtered solution) travels through the glomerular basement membrane (B) into the tubule (C), which reabsorbs essential filtered substances and transports wastes that end up in urine. The image at right shows how lupus nephritis (kidney inflammation) damages nephrons and their blood-filtering ability. In the glomerulus, vessels are crushed by multiplying layers of cells called crescents (D) that form scar tissue, and by multiplying structural support (mesangial) cells (E). Deposits of immune complexes (F) activate local and immune cells, triggering an inflammatory response that damages both the glomerulus and tubule.

A kidney (above left) contains about 1 million blood-filtering units called nephrons, each with a glomerulus (a cluster of tiny blood vessels) and a tubule (see healthy nephron, center). Blood is filtered by vessels of the glomerulus (A), and the filtrate (the filtered solution) travels through the glomerular basement membrane (B) into the tubule (C), which reabsorbs essential filtered substances and transports wastes that end up in urine. The image at right shows how lupus nephritis (kidney inflammation) damages nephrons and their blood-filtering ability. In the glomerulus, vessels are crushed by multiplying layers of cells called crescents (D) that form scar tissue, and by multiplying structural support (mesangial) cells (E). Deposits of immune complexes (F) activate local and immune cells, triggering an inflammatory response that damages both the glomerulus and tubule.

While biopsies are essential for assessing the kidney health of lupus patients, doctors would prefer to limit their use. “Kidney biopsies are a routine procedure but are still invasive,” says Chaim Putterman, M.D., professor of medicine and of microbiology & immunology and chief of the division of rheumatology in the department of medicine at Einstein and at Montefiore. “When you take a large needle and stick it into a highly vascular organ, it’s not surprising that one side effect can be bleeding.”

Skin biopsies may offer an alternative. “Blood vessels in the skin are exposed to the same circulating immune factors as blood vessels in the kidney,” Dr. Putterman says. “So one hypothesis we are studying is that the skin may mirror what is going on in the kidney.”

Until recently, testing this assumption would have been difficult if not impossible. Now a new tool called single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) offers researchers a detailed glimpse at the inner life of a cell, including what genetic pathways are active and which genes are driving those pathways.

Dr. Putterman and his colleagues biopsied the kidneys of lupus patients with nephritis and used scRNA-seq to assess the gene-expression profiles of individual tubule cells. Cells from all patients exhibited heightened expression of genes known to be activated by interferon—an inflammatory chemical that contributes to tissue damage in patients with lupus.

Moreover, when scRNA-seq was performed on individual skin cells of lupus nephritis patients and of healthy controls, interferon-responsive genes were activated in the patients’ skin cells but not those of the controls. These findings, generated by a team led by Evan Der, a Ph.D. student in the Putterman laboratory, and reported in 2017 in JCI Insight, suggest that scRNA-seq analysis of skin cells could one day replace routine kidney biopsies.

The findings suggest that scRNA-seq analysis of skin cells could one day replace routine kidney biopsies.

In a second scRNA-seq study, published in abstract form in 2018 in The Journal of Immunology, Dr. Putterman, Mr. Der, and colleagues found that scRNA-seq analysis of kidney cells could differentiate among several types of lupus nephritis and predict which patients would not respond to standard treatment to suppress the immune system.

“Clinically, using scRNA-seq to predict treatment outcomes would be a huge advance,” Dr. Putterman says. “We now start off treating patients with drug A and, if that hasn’t worked after a few months, we then move to drug B. With scRNA-seq testing, we could promptly tailor treatment to a patient’s particular type of nephritis and predict which patients will require especially aggressive therapy to prevent end-stage kidney disease.”

Both studies were conducted as part of the Multi-Ethnic Translational Research Optimization (METRO) study, a collaborative effort involving scientists at Einstein, New York University School of Medicine (led by Jill Buyon, M.D.), and Rockefeller University (led by Hemant Suryawanshi, Ph.D., and Thomas Tuschl, Ph.D.), to leverage the power of scRNA-seq to decipher the molecular biology of lupus nephritis.

METRO in turn is part of the Accelerating Medicines Partnership program in rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, a unique partnership of the National Institutes of Health, pharmaceutical companies, and nonprofit organizations to develop novel lupus drugs by identifying promising new biological targets.

Discover how Einstein scientists are clearing up cutaneous lupus with nanoparticles.

One of METRO’s goals is to use scRNA-seq to better subclassify lupus patients. “Physicians tend to be ‘lumpers,’” says Dr. Putterman, who is leading Einstein’s component of the project. “So if you have a rash, along with arthritis and kidney disease, we call it lupus. But scientifically, that might not be correct. From mouse studies, we know that knocking out a gene in any one of 20 different immune pathways can lead to the same phenotype—lupus. So at least in the mouse and probably in humans as well, lupus is not one disease but rather several different diseases with a common set of symptoms. We have blanket treatments, when what we need are individualized treatments to address the biology underlying each type of lupus.”

METRO is also using scRNA-seq to investigate how race and ethnicity affect biological pathways in lupus. “If lupus differs from one population to another at the molecular level, as we suspect it does,” Dr. Putterman says, “these studies could help identify molecular targets for drug treatment so we can use our therapies more precisely.”

One might expect that hormones, estrogen in particular, would contribute to a disease that mainly strikes young women. But their role in lupus—while important—is far from clear. For example, some studies in which female lupus patients are prescribed estrogen, either via birth control pills or as postmenopausal therapy, have found no significant increase in disease activity.

Genes are also important in lupus, with more than 50 gene variants associated with the disease. In addition, 20 percent of lupus patients have a parent or sibling who already has lupus or develops it. Yet “lupus genes” aren’t a sufficient cause, since the chance that an identical twin of a lupus patient will also develop the disease is between 15 and 25 percent. Unidentified factors such as viruses probably trigger lupus in genetically susceptible people.

Organ damage in lupus and other autoimmune diseases can result from antibodies directed against the body’s own tissues. To diagnose lupus, doctors look for autoantibodies unique to the disease: those made against double-stranded DNA. Presumably, the immune system encounters double-stranded DNA when cells die and spill their DNA into the blood. But how do the resulting anti-double-stranded-DNA antibodies cause the destructive inflammation that characterizes lupus?

In seeking the mechanism for antibody-caused inflammation, lupus researchers have focused on lupus nephritis, a leading cause of mortality among systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Finding the answer could lead to strategies for preventing lupus inflammation from occurring, both in the kidney and elsewhere in the body. Several theories have been proposed.

Antibodies bind to double-stranded DNA to form large molecular complexes, and the kidneys filter a quarter of the body’s blood (along with those large complexes) every minute.

Many lupus experts have theorized that these antibody-DNA complexes become stuck in the kidney and, in so doing, trigger kidney inflammation.

“The problem with that theory is the lack of evidence that the kidney has difficulty clearing those antibody-DNA complexes,” Dr. Putterman says. “Instead, those antibodies are probably cross-reacting with an antigen that resembles DNA, and our research strongly suggests they’re binding to an antigen on kidney cells. But it’s likely there are several ways by which anti-DNA antibodies damage the kidney.”

Other autoantibodies—antiphospholipid antibodies—increase the risk that lupus patients will have recurrent miscarriages. Phospholipids are normal cellular components; antibodies against them can cause blood clots to form, which may contribute to miscarriage by preventing blood from reaching the placenta.

By taking anticlotting drugs such as aspirin, female lupus patients diagnosed with antiphospholipid antibodies have an excellent likelihood of successful pregnancies.