Four billion years ago, when the first gene awoke within the first primordial cell and life began, that first gene may well have coded for an enzyme.

Vern Schramm, Ph.D.: His journey to Einstein and his contributions to science and health.

Vern Schramm, Ph.D.: His journey to Einstein and his contributions to science and health.

Clockwise from top: The traveling carnival operated by Vern’s family; Vern at age 20; Vern at age 10; and Vern, second from left, with carnival friends.

Clockwise from top: The traveling carnival operated by Vern’s family; Vern at age 20; Vern at age 10; and Vern, second from left, with carnival friends.

Ask Vern Schramm about his earliest memory and he’ll take you back to a hot Midwestern summer in the early 1940s: a 3-year-old traveling with a carnival on dusty roads through South Dakota and into Iowa and Minnesota—four days entertaining folks in one small town, then packing up and moving to another.

“The carnival was the family business—the brainchild of my maternal grandfather, who started it in 1926,” he recalls. “It was a pretty big operation and needed five semitrailer trucks to transport everything. It had a Ferris wheel, several rides like the Tilt-a-Whirl with its spinning cars, many sideshows—throwing balls at a pyramid of bottles to win a teddy bear, that kind of thing—along with a few monkeys and two elephants named Judy and Alice.”

The third of five children, Vern (as he likes to be called) was born in 1941 in the small town of Howard, South Dakota (population 1,000), where the carnival was based. He was born at home, not in a hospital—standard for that time and place.

Vern’s mother, Goldie Lee, had graduated as Howard High School’s valedictorian. His father, Roger Schramm, had interrupted his education in sixth grade, when he left his family’s South Dakota farm for life on his own. He’d supported himself in winters by running a trap line and working as a mechanic and jack of all trades—automobile repair, wiring, construction. He worked as a carnival roustabout during summers, which is how he met Goldie.

The carnival’s turning point, so to speak, came in 1944, when Vern’s older sister Carol got too close to the Tilt-a-Whirl and broke her foot. Goldie was already tired of the carnival life and its dangers, of raising a family in a trailer while living on the road for months at a time. She declared she’d had enough, and the carnival was sold in 1946. Lee Electric, the family’s winter business, now became a full-time operation.

The Lee Electric storefront was full of televisions, washing machines, and dryers, either for sale or in various stages of repair. But for Vern, the machine shop in back was the place to be: a huge space once used for repairing carnival equipment during the winter, still filled with broken merry-go-round horses and other carnival remnants and the machines and welding torches for fixing them. “It was an amazing place where you could do anything with metal,” he says. “My brother and I had free rein to go back there, and we’d weld and cut and torch. That was our playground during childhood, which I think contributed to my inventive nature.”

Vern credits his interest in chemistry to his Gilbert chemistry set, a Christmas gift from his parents. “Chemistry sets in those days had compounds like sulfur and potassium nitrate and, of course, we could make charcoal ourselves. With all the ingredients for gunpowder, I helped my brother and his friend the preacher’s son make Fourth of July fireworks. This inspired me to try making nitroglycerin—but fortunately I wasn’t a very good chemist at age 12 and never blew anything up. But I certainly tried.”

A Gilbert chemistry set.

A Gilbert chemistry set.

His other passion was reading. “I read all the time when I was in high school,” Vern says. “I read encyclopedias, books about chemistry, the classics—almost all the books in our high school library.” He was not a good student, however. “I liked to learn but didn’t like to study,” he recalls. “I didn’t have really good grades, and after high school I went to our local college, South Dakota State College of Agricultural and Mechanic Arts, where they were obliged to take anyone who’d been in good academic standing during high school.”

Not surprisingly, he majored in chemistry. But in his junior year, while taking a course in microbiology, he was offered a research assistantship and free tuition if he’d switch to a microbiology major, which he did. He stayed on after graduating, working full-time as a technician with no plans for the future. Then came the phone call that changed his life.

“One day at school I got a call from someone at the Harvard School of Public Health wondering if I’d like a fellowship to complete a master’s degree in the department of nutrition. I said ‘Yeah, okay.’” Unbeknownst to Vern, South Dakota State’s chair of microbiology had recommended him to a good friend who worked in the department.

“Going from South Dakota State to Harvard was like moving to outer space,” says Vern, who—aside from his forays with the family carnival—had ventured out of state just once before.

As Vern was finishing his master’s degree, he spotted an ad on a Harvard Medical School Library bulletin board. The Australian National University (ANU) was seeking Ph.D. students. By then he had married Deanna, a South Dakota State classmate, and the couple had an infant daughter. His application to the Ph.D. program in biochemistry was accepted, and he and his family were soon headed for Canberra, Australia.

John Morrison, the ANU professor who’d informed Vern of his acceptance and took him on as a grad student, was a highly respected enzymologist. His special interest was tight-binding enzyme inhibitors, which would become a focus of Vern’s own scientific career.

“Morrison had just returned to Australia after a sabbatical at the University of Wisconsin with W.W. Cleland, the leading enzymologist in America at the time,” Vern says. “He brought Cleland’s technologies and ideas back to Australia, and I was the first student to come into his lab and benefit from them.”

Vern’s three-and-a-half years in Australia were eventful. The couple’s second daughter was born there, and the family took a six-week camping trip around Australia’s perimeter—a 9,000-mile journey on Highway 1, the world’s longest national highway. Only a fourth of the highway was paved, and gas stations sometimes were 300 miles apart.

“I cringe now to think of it, since our daughters were only 6 months and 3 years old,” Vern recalls. “We began the trip without enough money to make it around and assumed we could find some work along the way, and we did. We got a job on a truck farm that paid us by the pole for placing bamboo poles in a field of climbing beans. The other workers prevented us from working a second day because we were working too fast, but we’d made enough money to get us on our way.”

After earning his doctorate in biochemistry at ANU, Vern returned with his family to the United States, where he was awarded a post-doctoral fellowship funded by the National Research Council and the National Science Foundation. With his pick of any federally funded research laboratory, he chose NASA’s Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California.

“NASA-Ames had an enzyme division that was studying extreme environments,” Vern says. “They were asking, ‘If there’s life on Mars, what might enzymes be like in the microbes or other organisms we might find there?’ My fellowship allowed me to pursue independent postdoctoral research, and it was there I began work on what has remained my main interest, the enzymes involved in synthesizing and breaking down the nucleotide building blocks of DNA and RNA.” He earned a pilot’s license in his spare time.

Then came the search for a faculty position. It was 1971, a tough time for job hunters. “I must have applied for nearly 100 positions,” he recalls, “and I got one reply, from Temple University Medical School in Philadelphia. I gave a seminar and was offered a job as an assistant professor in the biochemistry department. A couple of months later, we moved to Philadelphia and I started my lab.”

It was a humbling introduction to the world of academe. “Today, you know, we offer sizable incentives to attract new assistant professors,” Vern says. “My start-up package was $3,000 to buy equipment and supplies, plus a summer student assistant to help paint the empty lab, which we did during my first two weeks.”

Despite its inauspicious start, Vern’s research career in enzymology was soon in full swing, funded year after year by grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. From the very beginning, he has studied the underlying mechanisms by which enzymes transform the chemicals they act on, known as substrates, into entirely different chemicals called products, and how those reactions occur so incredibly rapidly.

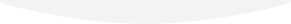

Rajesh Harijan, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Vern’s lab, examines enzyme-inhibitor molecules.

Rajesh Harijan, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Vern’s lab, examines enzyme-inhibitor molecules.

Turning base metals into gold—the classic claim of medieval alchemists—is modest compared to what enzymes do in a split second. Need to convert your starchy spaghetti meal into glucose molecules? The amylase in your saliva does the trick. Want your cells to metabolize glucose, along with protein and fats? Eight different enzymes act sequentially to change them into energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). And in what may be nature’s most impressive alchemical feat, green plants use enzymes and sunlight to transform carbon dioxide and water into glucose, cellulose, and oxygen.

Enzymes have evolved over millions of years to bind to certain substrates and catalyze reactions with optimal efficiency—typically 1010 to 1015 times faster than would be possible without them. An enzyme’s three-dimensional shape—its conformation—results from its amino-acid sequence. That shape, in turn, determines the enzyme’s specificity: the particular substrates it can physically attract.

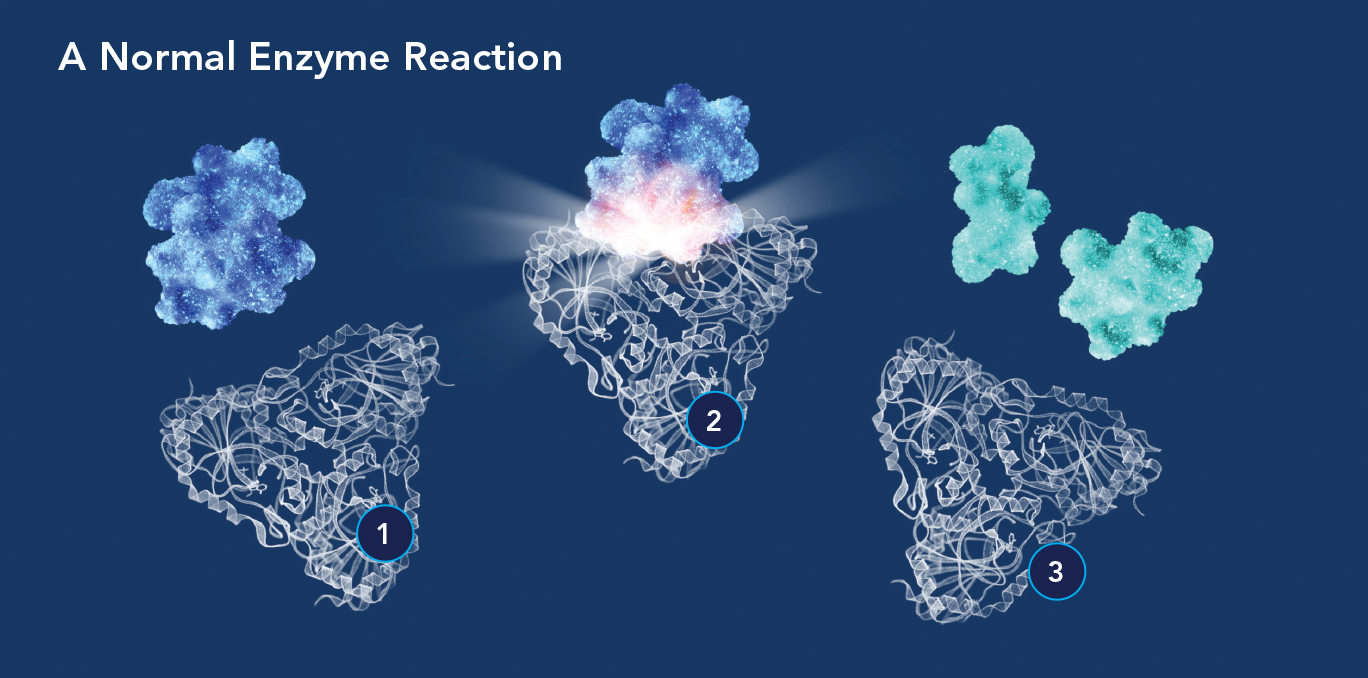

An enzyme molecule will bind to and interact with one substrate molecule after another. But only a small portion of the enzyme—its active site—binds the substrate molecule tightly enough to catalyze an enzyme reaction. The enzyme’s active site bristles with catalytic groups that break the substrate’s chemical bonds and rearrange its atoms to form a chemically different product. But for catalysis to occur—for substrate to become product—a structure called the transition state must form during the enzyme reaction.

Seventy years ago, two-time Nobel laureate Linus Pauling hypothesized that enzymes bind tightly to substrates at transition states, which accelerate the conversion of substrates into products. Vern’s great achievement was finding a way to visualize transition states’ incredibly brief lives—they exist for just a millionth of a billionth of a second—and use that information to attack some of humankind’s most intractable diseases.

Illustration by Margaret Nielsen

Illustration by Margaret Nielsen

Picture an octopus that has captured a fish (above), and explores it with all eight tentacles, seeking the optimal combination of grips to immobilize it: the tighter the collective grip, the faster the fish can be swallowed. Something similar happens when an enzyme captures a substrate molecule and clasps it to its active site.

Instead of tentacles, the enzyme’s active site uses its catalytic groups to explore the surface of the captured substrate, seeking interactions tight enough to break its chemical bonds and catalyze the reaction. Finally—and only when multiple interactions have reached optimal strength at exactly the same time—comes the transition state: a swirl of atoms and electrons amidst chemical bonds that are breaking and releasing energy to speed the reaction to completion. The fleeting transition state that forms is neither substrate nor product, but rather a ghostly combination of both of them.

The transition state is the beating heart of enzymology—and of life: Its formation provides the essential chemical changes needed for all of biology’s metabolic functions. But what did these essential but short-lived structures look like? Vern was well-suited to solve that mystery.

“Ever since I was an undergraduate, I’d been interested in how enzymes worked and how they perform amazing chemical reactions so hard to achieve using organic chemistry,” he says. “I wanted to know about the atomic chemistry that governs enzyme mechanisms and investigate enzyme kinetics—measuring how changing certain conditions alters reaction rates. I felt that to understand enzymatic reactions and how they proceed so fast, you needed to decipher the transition state’s atomic structure.”

Vern began that effort soon after arriving at Temple in 1971. Directly observing transition-state structures was impossible: They disappear far too quickly to be seen with imaging technology such as X-ray crystallography, which requires freezing compounds and then bombarding them with X-rays. He realized that the only way to “see” transition states was by measuring kinetic isotope effects: Swapping out a substrate’s hydrogen, carbon, and nitrogen atoms for their slightly heavier isotopes and observing how those slight changes alter the substrate’s reaction with its enzyme.

Leading enzymologists were skeptical that kinetic isotope effects could reveal anything useful about enzymatic reactions, but Vern was ultimately vindicated (see “The Power of Persistence”). “By combining kinetic isotope effects with physical chemistry measurements and quantum theory,” Vern says, “we were able to obtain a reliable picture of the transition state.”

In 1984, Vern and his colleagues published their first-ever transition-state structure, for the enzyme AMP nucleosidase. Over the next few years they solved transition states for half a dozen more. “This was purely fundamental research—science at its most basic,” he says. “Back then we’d given no thought to designing drugs.” That would come later, when Vern saw the therapeutic potential in targeting a single enzyme.

Transition states last for a millionth of a billionth of a second—far too brief a period to be observed directly. Vern knew that two features are needed to describe all molecular interactions in biology: their geometric shape and the distribution of their electrons. He realized he could use isotope effects to describe both features and, by doing so, solve the transition-state structures of enzymes.

Isotopes are different-mass versions of naturally occurring atoms, such as the hydrogen, carbon, and nitrogen atoms that typically form substrate molecules. An ordinary hydrogen atom, for example, has an atomic weight of one (one proton), while its isotope deuterium has an atomic weight of two (one proton plus one neutron). Isotopes soared to the forefront of scientific consciousness after World War II: tritium, for example—hydrogen’s heaviest isotope, with an atomic weight of three—was a key ingredient in the hydrogen bomb.

Kinetic isotope experiments involve taking the substrate of an enzyme reaction and replacing its hydrogen, carbon, and nitrogen atoms one by one with heavier isotopes. Running those mass-altered substrate variants one at a time through the enzymatic reaction gives an atom-by-atom readout of how those atoms respond to the transition state.

“Each atomic substitution alters the substrate’s bond-vibrational frequency in the transition state, causing a small but measurable change in the reaction time compared with the time required when the enzyme reacts with normal, ‘unsubstituted’ substrate molecules,” Vern says. “Those isotope effects on the reaction rate are exquisitely difficult to measure, but I love doing that analytical chemistry work.”

Combining the results of those isotope experiments provided crucial insights into the transition state’s geometric shape and electron distribution—information needed to deduce the transition state’s atomic structure. The final step: Use computational quantum chemistry to search through thousands of the enzyme’s theoretically possible transition states to find the model that most closely matches the experimental results from kinetic isotope studies.

“That structure is the most complete picture of an enzyme’s transition state that we can get,” Vern says. “Now that we have a blueprint of the transition state, we can design stable transition-state analogues that will mimic its structure and, we hope, powerfully inhibit that enzyme.”

Learn how persistence paid off for Vern, who used isotopes to find transition states despite the skepticism of his peers.

Each year several children in the world are born healthy but by age 3 or 4 become helpless against bacterial or viral infections because their infection-fighting T cells have disappeared. In 1975, University of Washington hematologist Eloise Giblett discovered the cause: A genetic defect meant the children couldn’t synthesize the enzyme purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP). Without PNP, the children’s T cells couldn’t multiply to fight infections, which overwhelm the limited number of T cells available to combat them.

Dr. Giblett’s discovery meant that children born with this condition could be saved through stem-cell transplants that normalize PNP levels. It also showed that purposely knocking out PNP could be a useful strategy against diseases caused by excess T-cells, especially since these children weren’t otherwise harmed by their lack of PNP. Vern and other scientists realized that a drug specifically targeting PNP would have tremendous health implications.

Two types of blood cancer—T-cell leukemia and T-cell lymphoma—result from rapidly dividing T cells. In addition, most of the more than 70 autoimmune diseases are caused by dividing T cells that mistakenly attack a person’s own tissues. A drug that specifically inhibits PNP would presumably work against all of them.

Also in the 1970s, enzymologist Richard Wolfenden at the University of North Carolina was working on a strategy for inhibiting enzymes. He’d followed up on Linus Pauling’s idea that enzymes bind tightly to their substrates during the transition state and was writing equations to show how that happens. When substrate and enzyme are together at the transition state, his equations predicted, the energy buildup that occurs as the substrate’s bonds are broken will dramatically increase the strength of enzyme-substrate binding by a factor of 1010 to 1015. The tighter the binding at the transition state, the faster the reaction can proceed.

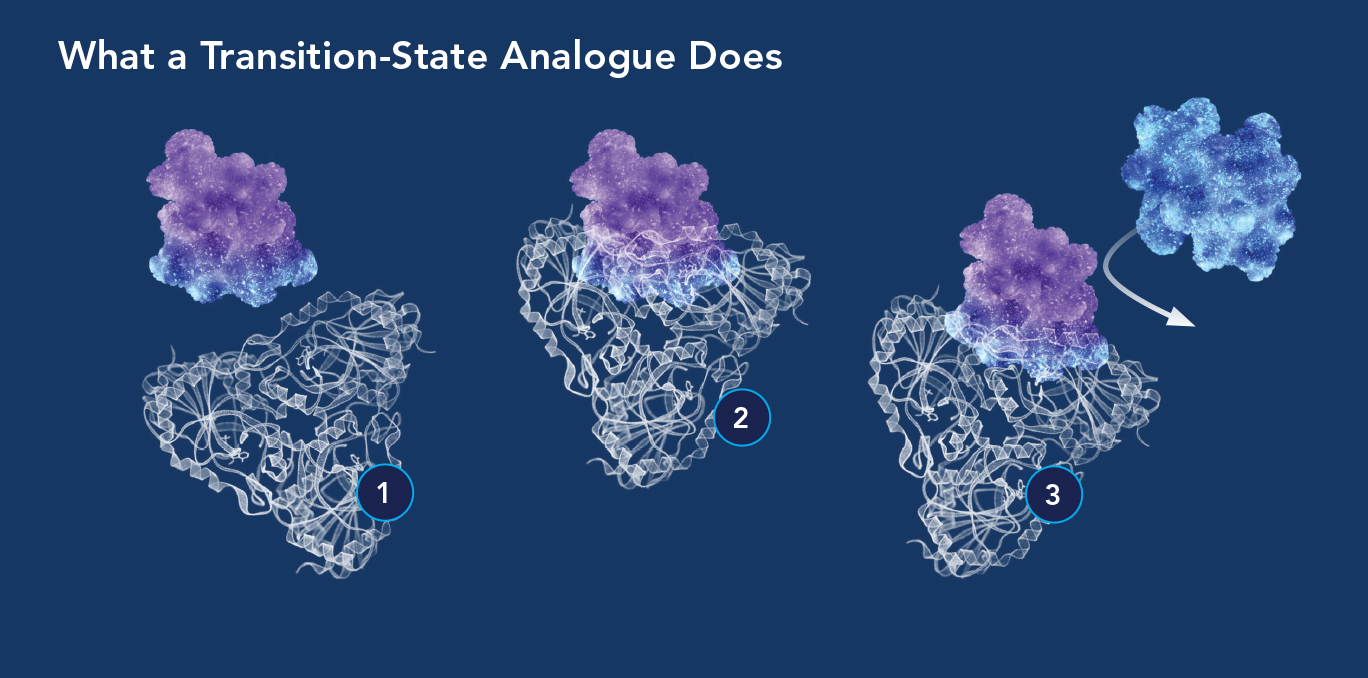

If scientists could develop what Wolfenden dubbed transition-state analogues—compounds combining features of the substrate, the transition state, and the product—something else should occur: In a sea of thousands of substrate molecules, an enzyme molecule would preferentially seek out a lone transition-state analogue molecule, enticed by the prospect of forming a transition-state structure with what resembles a substrate molecule.

But unlike a “real” substrate molecule, the analogue resists chemical change when the enzyme binds to it. So now the enzyme—rather than propelling a chemical reaction—finds itself part of a stable duo: imprisoned by the analogue and bound to it millions of times tighter than if the enzyme had met up with an actual substrate molecule.

“Wolfenden’s work set the stage for the search for transition-state analogues,” Vern says. “But until we started our research there was no way to understand what an enzyme’s transition state looked like and therefore no way to rationally design stable transition-state analogue molecules that mimic it. We realized that solving the transition state for any enzyme would put us in a good position for designing analogues to inhibit it, including PNP.”

(1) An enzyme molecule’s active site is attracted to and binds with a substrate molecule (blue); a transition state then forms (2) to accelerate the substrate’s conversion into a product or products (3).

(1) An enzyme molecule’s active site is attracted to and binds with a substrate molecule (blue); a transition state then forms (2) to accelerate the substrate’s conversion into a product or products (3).

Transition-state analogues inhibit the enzyme reactions that cancer cells, parasites, and other disease-causing cells depend on. (1) The enzyme molecule is attracted to what appears to be a substrate molecule but is actually a transition-state analogue (blue-purple molecule); (2) the analogue binds the enzyme millions of times more tightly than a normal substrate molecule would, because the analogue’s bond-breaking energy is converted to binding energy; (3) with the enzyme’s active site permanently blocked by the analogue, it can no longer react with substrate molecules.

Transition-state analogues inhibit the enzyme reactions that cancer cells, parasites, and other disease-causing cells depend on. (1) The enzyme molecule is attracted to what appears to be a substrate molecule but is actually a transition-state analogue (blue-purple molecule); (2) the analogue binds the enzyme millions of times more tightly than a normal substrate molecule would, because the analogue’s bond-breaking energy is converted to binding energy; (3) with the enzyme’s active site permanently blocked by the analogue, it can no longer react with substrate molecules.

By the mid-1980s, Vern’s career was flourishing as he pursued PNP’s transition state: He was a tenured professor at Temple, had no trouble getting research grants, and served as a member of the National Institutes of Health’s biochemistry study section, which evaluated grant proposals for the NIH. He had become friends with another study-section member, Einstein’s Charles Rubin, Ph.D., who told Vern that Einstein was recruiting a chair of biochemistry and that he should apply.

“I told him I was too young to be a chair and didn’t want to live in New York,” Vern recalls. “But Charles kept nagging me, and I finally agreed to give a seminar at Einstein in the fall of 1986. I was invited for a second visit in January 1987, but over the Christmas holiday I broke my right leg in a skiing accident and was in a cast from my toes to my upper thigh. I called Einstein to cancel the visit, but Dominick Purpura, the dean at the time, insisted I come and sent a car from New York to Philadelphia with two drivers to carry me if necessary.”

Vern was offered the position of biochemistry chair soon afterward and agreed to assume the job while continuing with his transition-state research. “When I started at Einstein in August 1987 I was still limping from my ski accident,” he recalls.

In 1993, nine years after publishing his first transition-state paper, Vern and his colleagues solved PNP’s transition-state structure. The next step—using that structure as a blueprint for synthesizing transition-state analogues for use as drugs—would prove to be formidable. Several chemists considered the structure too difficult to duplicate. Others had tried synthesizing molecules resembling the transition-state structure but failed. Luckily, some chemists halfway around the world were looking for a challenge.

The chemists worked at Industrial Research Ltd., a government research institute in Lower Hutt, New Zealand. One day in 1991 they were visited by Paul Atkinson—a former Einstein biology professor, friend of Vern, and native New Zealander. He’d recently moved back home to direct AgResearch, a New Zealand government research facility. He soon learned that another research team—the Carbohydrate Chemistry Group—was looking for new partners.

“Paul knew about my work here at Einstein,” Vern says, “so he told the team leader, ‘You should go talk to Vern Schramm. He’s doing some interesting carbohydrate chemistry that you might want to get involved with.’”

Vern (second from left) with his New Zealand collaborators, from left: Peter Tyler, Ph.D., Gary Evans, Ph.D., and Richard Furneaux, Ph.D.

Vern (second from left) with his New Zealand collaborators, from left: Peter Tyler, Ph.D., Gary Evans, Ph.D., and Richard Furneaux, Ph.D.

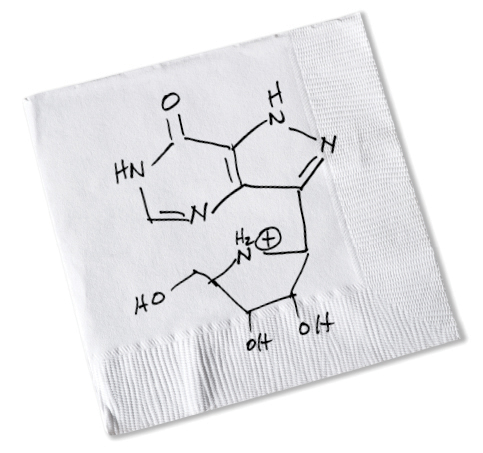

Richard Furneaux and Peter Tyler, New Zealand chemists, arrived in the Bronx a year later. “After discussing transition states in my office, we drove to a waterfront restaurant in New Rochelle,” Vern recalls. “Over drinks, I sketched on a bar napkin the structure of a molecule I thought would be a good transition-state analogue for PNP. The concept of transition states was new to them, but they understood the chemistry needed to synthesize the inhibitor I wanted.”

Vern and his new partners shook hands and agreed that their two institutions would share equally in any revenue arising from their collaboration. “It’s truly been a great partnership—one that has worked really well for 25 years and counting,” Vern says.

Back in New Zealand, synthesizing what became known as “the bar-napkin inhibitor” was a difficult four-year effort requiring 21 steps. Finally, the first PNP transition-state analogue was successfully synthesized, nearly identical in structure to Vern’s bar-napkin sketch. Then came a crucial test.

To be an effective drug, the inhibitor had to do what Wolfenden had predicted for a transition-state analogue: bind PNP thousands of times more tightly than PNP binds its usual substrate. The actual results were even better than Vern had hoped for: His analogue bound to PNP nearly one million times tighter than PNP’s normal substrate. Further testing showed that rapidly dividing T cells from patients with T-cell cancers readily absorbed the analogue, bringing cell division to halt.

Vern sketched on a bar napkin the molecule he thought would work to inhibit the enzyme PNP. Mundesine, approved in Japan in 2017, closely resembles Vern’s original sketch.

Vern sketched on a bar napkin the molecule he thought would work to inhibit the enzyme PNP. Mundesine, approved in Japan in 2017, closely resembles Vern’s original sketch.

In 2000, Einstein licensed the analogue to a commercial partner, BioCryst Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for testing against blood cancers. BioCryst took the analogue through phase 2 human trials and then sublicensed it to Mundipharma, which brought it through pivotal clinical trials leading to regulatory approval. This first of Vern’s PNP inhibitors, now known as Mundesine®, was approved in Japan in 2017 for treating advanced cases of peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

It took 20 years for Vern’s PNP inhibitor to become the approved drug Mundesine®. Ironically, the drug’s potency prolonged its approval process. “Pharmaceutical companies didn’t understand how to use transition-state analogues at first,” he says. “There was a big learning curve before they realized just how effective these compounds are at very low doses.”

Indeed, just a few milligrams of Mundesine® stops T cells throughout the body from dividing. Moreover, like pharmaceutical laser beams, Mundesine® targets a single enzyme while sparing the thousands of others in the body’s billions of other cells. This specificity is what makes Mundesine® and other transition-state analogues unique.

Ordinary chemotherapies can cause serious side effects by killing dividing cells, both normal and cancerous, throughout the body. But Mundesine® affects only rapidly dividing T cells that cause blood cancers. Here’s how it works:

Rapidly dividing cancerous T cells urgently need deoxyguanosine (dGuo), a precursor compound for making DNA. But the presence of the enzyme PNP in human blood suppresses dGuo levels so that it’s normally present in just trace amounts. As a result, cancerous T cells must rev up their metabolic machinery to obtain every possible scarce dGuo molecule.

When Mundesine blocks PNP throughout the body, blood levels of dGuo surge and wash over cancerous T cells in a veritable tsunami. Primed as they are to absorb and use as much dGuo as possible, the cancerous T cells are now overwhelmed by too much of a good thing: dGuo accumulates to toxic levels within T cells and kills them. Thanks to its highly specific mode of action, Mundesine is well tolerated and causes few serious side effects; it’s one of the few anticancer agents that can make that claim.

The packaging for Mundesine tablets, now on the market in Japan. Photos courtesy of Mundipharma.

The packaging for Mundesine tablets, now on the market in Japan. Photos courtesy of Mundipharma.

Basic scientists like Vern rarely know if their work will affect human health. “Fundamental discoveries are usually single steps in a long path toward applications,” Vern says. “Typically you wouldn’t even know if you’ve contributed to a new drug.” But Vern was lucky: long before Mundesine was approved for use in Japan, he learned that the drug he designed could save lives.

Mundesine’s approval in Japan for T-cell lymphoma came after 19 clinical trials that spanned 10 years and involved about 500 patients with several types of cancer. The trials were intended for adults; but an early exception was made for a 2-year-old California girl (at right) with T-cell leukemia, for which Mundesine has not yet been approved.

“We heard that the girl—we didn’t know her name—had failed all standard therapies for T-cell leukemia,” Vern says. “As a father, I could imagine how devastating that must be for a family. The company sponsoring her trial received periodic reports from her grateful dad, and their emotional impact exceeded anything else I’d experienced as a scientist.” Vern finally learned more about the successful treatment of the girl, Katie Lambertson, from a 2014 magazine article.

The 10-Step Recipe for Making

Enzyme Inhibitors

The 10-Step Recipe for Making

Enzyme Inhibitors

1. Target an enzyme…

1. Target an enzyme…

2. Isolate and purify...

2. Isolate and purify...

3. Label the substrate...

3. Label the substrate...

4. Use computational

quantum chemistry...

4. Use computational

quantum chemistry...

5. Design an analogue structure...

5. Design an analogue structure...

6. Collaborate with Colleagues...

6. Collaborate with Colleagues...

7. Do lab testing...

7. Do lab testing...

8. Learn whether the analogue...

8. Learn whether the analogue...

9. License the

9. License the  10. Pop the champagne...

10. Pop the champagne...

Over the past 15 years, Vern and his New Zealand colleagues (now at the Ferrier Research Institute of Victoria University of Wellington) have developed even more powerful second- and third-generation transition-state analogues. They’re intended for use against the numerous health problems traceable to PNP and other enzymes.

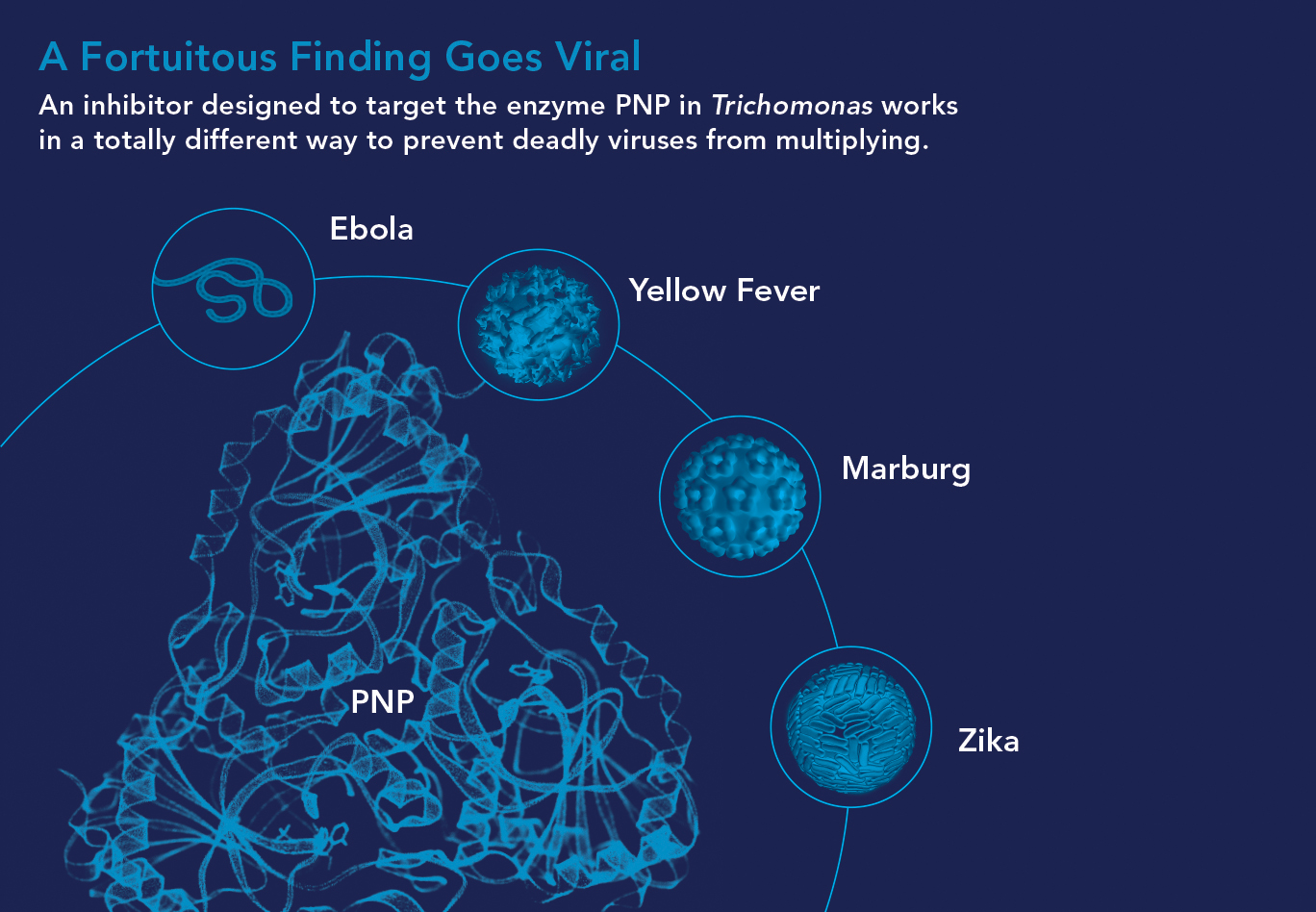

• From STDs to Deadly Viruses. Thanks to serendipity, an analogue dismissed as a failure may soon become the first broad-spectrum antiviral agent, effective against some of the world’s most lethal viruses.

The protozoan parasite Trichomonas vaginalis seemed a perfect target for a PNP inhibitor. It causes trichomoniasis or “trich,” one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases. And the parasite’s unique version of PNP meant that inhibiting it wouldn’t harm people.

“We synthesized a transition-state analogue we called Immucillin A for this target,” Vern says. “It did a terrific job inhibiting the enzyme but failed to kill the parasite.” PNP, it turned out, was not essential for the parasite’s survival. But later, when BioCryst tested all its Einstein-licensed drugs against viruses, Immucillin-A prevented more than 20 RNA viruses from multiplying. Four were particularly notorious: Ebola, Marburg, Zika, and yellow fever.

Immucillin-A doesn’t actually function as a transition-state analogue against viruses. Instead, virus-infected cells absorb the analogue and metabolize it into RNA building blocks that are defective; replicating viruses unwittingly use the defective RNA building blocks, which sabotage their efforts to multiply.

“That was something we never could have predicted from our own work,” Vern says. “I credit Einstein’s office of biotechnology & business development, which Executive Dean Ed Burns created in 2000, for finding commercial partners like BioCryst to give our discoveries the best possible chance of being turned into drugs.”

BioCryst teamed with U.S. government agencies to further develop the analogue, now called galidesivir. It was found safe when given intramuscularly to healthy human volunteers.

BioCryst has reported the results of studies in which nonhuman primates were infected with lethal doses of the Marburg or Ebola virus. Forty-eight hours later, they received injections of galidesivir—which allowed them to survive the otherwise fatal infections. Galidesivir also demonstrated antiviral effects in nonhuman primates infected with the Zika virus.

Following more studies involving animals infected with Ebola and Marburg, galidesivir will be evaluated in additional human safety trials. If those tests are successful, galidesivir may then be manufactured and stockpiled for use in future outbreaks of the viruses.

• Malaria. While Ebola is scary but rare, malaria—caused by single-celled parasites belonging to the Plasmodium genus, is common—and causes many more deaths: an estimated 429,000 per year, 90 percent of them in Africa and more than half of them involving young children.

Vern and his colleagues were eager to develop and deploy enzyme inhibitors against this devastating Third World disease. They targeted Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest malarial species, by exploiting its Achilles’ heel: It can’t directly synthesize purines, the vital building blocks for making DNA.

Instead, the parasites need their own version of PNP to make hypoxanthine, which they then convert to purines. Inhibiting P. falciparum’s PNP would cut off its supply of hypoxanthine—and thereby deprive the parasite of the purines it needs to survive. A PNP inhibitor, now called BCX4945, was developed to do just that.

BCX4945 proved effective against laboratory cultures and was then tested on three nonhuman primates infected with a strain of P. falciparum that is lethal without antimalarial therapy. When orally administered twice a day for seven days, BCX4945 cleared the infections from all the animals between the fourth and seventh day of treatment. No signs of toxicity were observed.

Results were announced in 2011, but the inhibitor has yet to be evaluated in human trials. “It’s frustrating to have a potential cure for malaria sitting on the shelf,” Vern says, “but the downside of licensing your compounds is that you lose control over which ones are developed. Companies are sometimes reluctant to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on human trials if sales can’t replace development costs.”

In a 2014 report, the World Health Organization called microbial resistance to antibiotics “an increasingly serious threat to global public health” and offered this warning: “The problem is so serious that it threatens the achievements of modern medicine. A post-antibiotic era—in which common infections and minor injuries can kill—is a very real possibility in the 21st century.”

By wiping out most microbes they encounter, standard antibiotics actively select for antibiotic-resistant strains. The few microbes that inevitably survive the antibiotic onslaught can multiply and thrive in a milieu free of competitors. Survivors transmit their resistance traits to succeeding generations, requiring ever more potent antibiotics, leading to bacterial strains that show even greater resistance: a vicious and dangerous cycle.

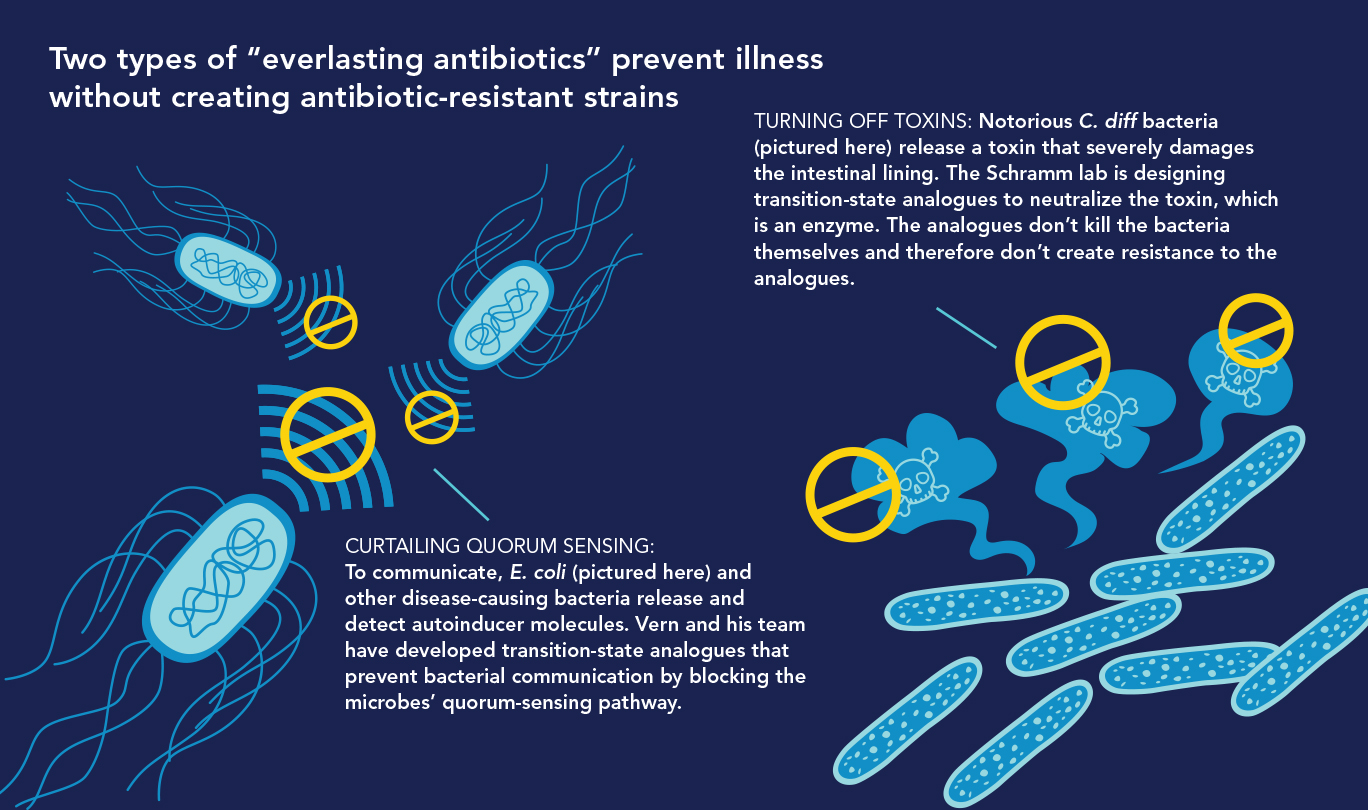

In Vern’s lab, a top priority is developing new antibiotics—enzyme inhibitors that “disarm” rather than destroy disease-causing bacteria. These drugs, which Vern dubs “everlasting antibiotics,” could treat infections without exerting the selective pressure that produces antibiotic-resistant strains. One type works by sabotaging communication among bacteria, and another by neutralizing disease-causing toxins. “Bacteria disarmed in these ways will simply join the body’s billions of other harmless bacteria,” Vern says.

• Quelling Quorums.Bacteria communicate via quorum sensing, in which individual bacteria produce and detect signaling molecules called autoinducers that tell them how many of their colleagues are nearby. Sensing a high number of autoinducers tells disease-causing bacteria that their colleagues are present in sufficient numbers (i.e., a quorum) to change from bystander to virulent mode—attacking their hosts by releasing toxins and forming slime-coated, hard-to-treat biofilms responsible for infections that often afflict people who have indwelling catheters.

“We hypothesized that blocking the quorum-sensing pathway in bacteria would cut the telephone wires and prevent them from transmitting their ‘Make toxin! Create biofilm!’ attack messages to each other,” Vern says. He knew that the bacterial pathway for synthesizing autoinducers required an enzyme called MTAN, so he and his colleagues designed and developed a family of transition-state analogues to target it.

The MTAN inhibitors were cultured overnight with the toxin-forming bacterial species Vibrio cholera (the species that causes cholera) and E. coli 0157:H7 (a potentially lethal strain of E. coli). The inhibitors disrupted quorum sensing in both species and significantly reduced biofilm production—without killing the bacteria. “The MTAN quorum sensing pathway isn’t essential for the survival of these bacteria,” Vern says. “So they’re not killed by our MTAN inhibitors and therefore shouldn’t develop resistance to them.”

To see if bacteria might eventually develop resistance, Vern’s lab grew 26 successive generations of the Vibrio and E. coli bacteria, all of them cultured with one of the quorum-sensing inhibitors. “The 26th generation of both bacterial species was just as sensitive to the inhibitor as the first was,” he says.

• Turning Off Toxins. The intestinal bacterium Clostridium difficile can be lethal and is difficult to treat. Infections with C. diff, as it’s called, predominate in hospitals, where antibiotic use is common. Today’s powerful antibiotics can deplete much of a person’s healthy gut microbiome but usually don’t eliminate C. diff, which can then flourish in the gut. Ever more powerful antibiotics have recently spawned increases in highly virulent, antibiotic-resistant C. diff strains.

C. diff sickens about half a million Americans yearly and causes about 30,000 deaths. Illnesses and deaths occur because C. diff releases toxins that damage the gut wall, leading to diarrhea and potentially fatal colitis. Toxin B, the major tissue-damaging toxin, is an enzyme. In a novel approach to disarming C. diff, Vern and his team are designing transition-state analogues against C. diff’s toxin B and not the bacteria themselves.

“C. diff would not know that these anti-toxin compounds are present,” Vern says, “so there’s no pressure on the bacteria to develop resistance to them.”

Vern targets enzymes that fuel solid tumors, including lung, prostate, and head and neck cancers.

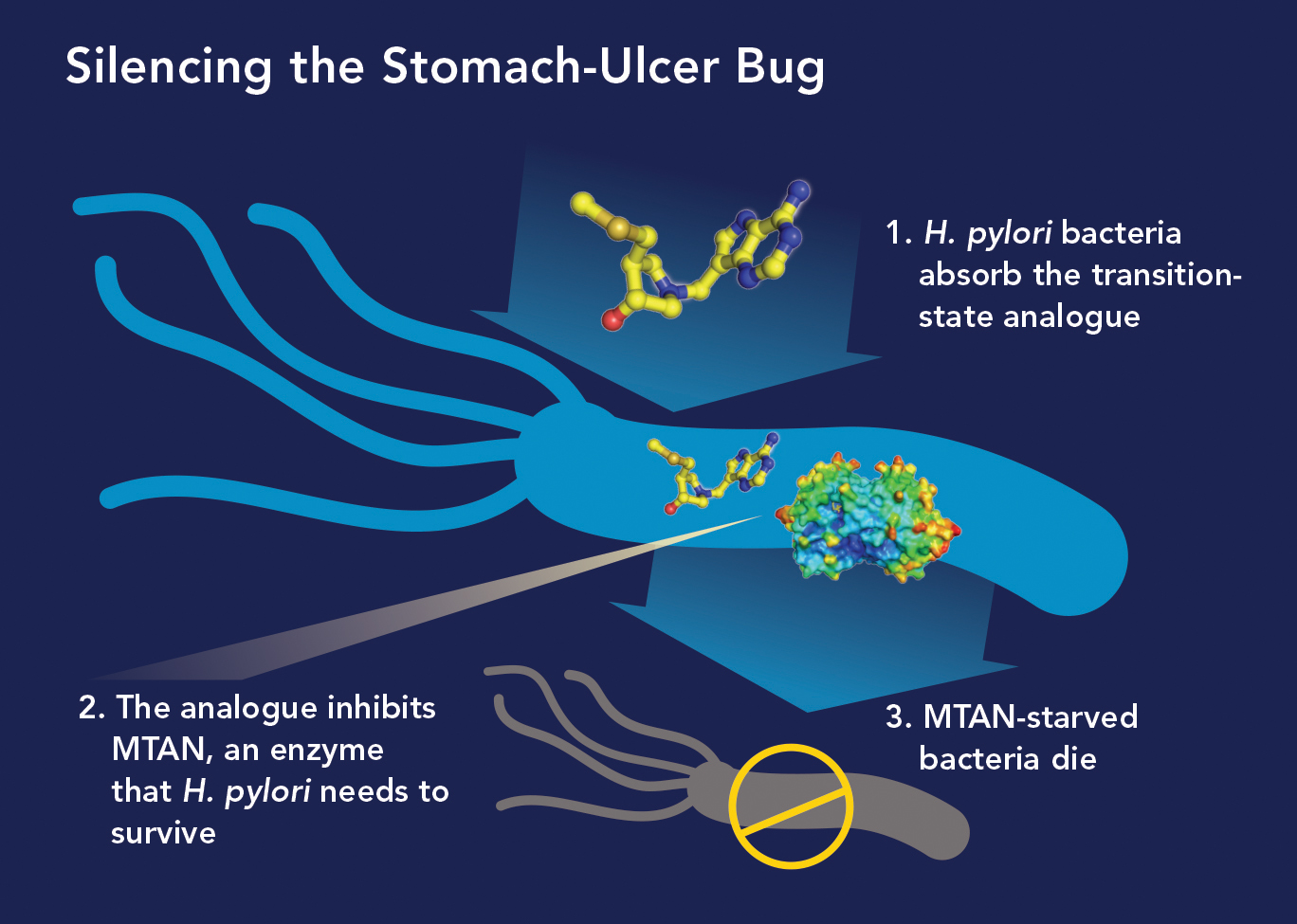

In 1982, Australian scientists Barry J. Marshall and J. Robin Warren reported that a previously unknown bacterial species called Helicobacter pylori causes most cases of stomach ulcers and duodenal (small intestine) ulcers, which had long been thought to result from stress or other lifestyle factors. The discovery earned Marshall and Warren the 2005 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine and transformed ulcers from a chronic, often disabling condition to a bacterial disease curable with antibiotics.

Over the past 30 years, however, H. pylori has become increasingly resistant to antibiotics. Even today’s extra-intensive antibiotic regimen fails to eradicate H. pylori in 20 percent of patients. Moreover, antibiotics plays havoc with patients’ normal gut microbiome, clearing the way for C diff to establish itself.

A 2017 study that followed 260 stomach-ulcer patients treated with H. pylori eradication therapy found a “significant rate” of C. diff colitis: 12 of the patients—4.6 percent of the total—developed the often-fatal illness. There was clearly a need for antibiotics that eliminate H. pylori without putting patients’ lives at risk.

In the midst of his quorum-sensing research targeting the enzyme MTAN, Vern read that H. pylori had a very unusual metabolic pathway. It depends on MTAN not for quorum sensing but for survival. “We realized our MTAN inhibitors that halted quorum sensing in other bacteria could work as antibiotics against H. pylori, and that’s exactly what we found,” he says.

In research published in 2015 in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, Vern and his colleagues reported that 10 of their MTAN inhibitors were up to 2,000 times more powerful at preventing H. pylori growth than many antibiotics now used to treat the infections.

“We think our MTAN inhibitors will capture the market for treating stomach ulcers,” he says. “They’re far more potent than existing H. pylori antibiotics, and our studies found they don’t harm normal gut bacteria and so won’t increase patients’ risk for developing C. diff infections—a major drawback to current ulcer therapy.” Several of those inhibitors were recently licensed to a biotech company interested in developing them into H. pylori drugs.

Vern is developing compounds that may reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and prevent superbugs from chewing up antibiotics.

Yacoba Minnow, a Ph.D. student in Vern’s lab, carries out pipetting for an experiment.

Yacoba Minnow, a Ph.D. student in Vern’s lab, carries out pipetting for an experiment.

Modern medicine emphasizes finding drugs that target enzymes. Yet when it comes to developing drugs using transition-state analysis, Vern and his New Zealand collaborators have few rivals—which is surprising, because the strategy epitomizes rational drug design.

“Companies designing enzyme inhibitors typically start by randomly searching through millions of compounds in their chemical libraries, hoping they’ll chance on one that inhibits their target enzyme,” Vern says. “They’ll find something that works pretty well and spend years refining that compound for clinical trials. We, however, start by identifying the enzyme we want to target. Once we solve its transition state, we synthesize a transition-state analogue to mimic it. If we’ve done things correctly, that analogue becomes the compound that will go into clinical trials.”

His different approach, he notes, “requires many cutting-edge scientific technologies that pharmaceutical companies find daunting.” But he predicts they’ll see the light. “If we get three or four drugs FDA-approved using this process, which could occur in the next decade, transition-state analysis will become a standard procedure that pharmaceutical companies will use to design and develop new drugs.”

As for his own research, he says, “the enzymes we’re now targeting are posing some very tough challenges—transition states that are hard to solve and analogues that will be difficult for our New Zealand colleagues to synthesize.” But he thrives on such challenges.

“You have to be optimistic as a scientist,” Vern says. “There are always four reasons to think an experiment might fail, but you’ve got to do the experiment anyway and be prepared for all those failures before you do the correct one. That sense of optimism helps us move forward. There are a lot more enzymes out there that we need to target.”