Bronx resident Betty Baumel, 87, is busy. Since losing her husband, Abraham, two and a half years ago to Alzheimer’s disease, she has taken to spending time at the local senior center, singing with a chorus, attending lectures, and taking pottery classes. That’s when she’s not dancing, visiting with one or more of her seven grandchildren, having lunch with friends, or riding the bus into Manhattan for workshops at the Museum of Modern Art.

At top: Betty Baumel at exercise class. Above: Ms. Baumel with Amy Ehrlich, M.D.

At top: Betty Baumel at exercise class. Above: Ms. Baumel with Amy Ehrlich, M.D.

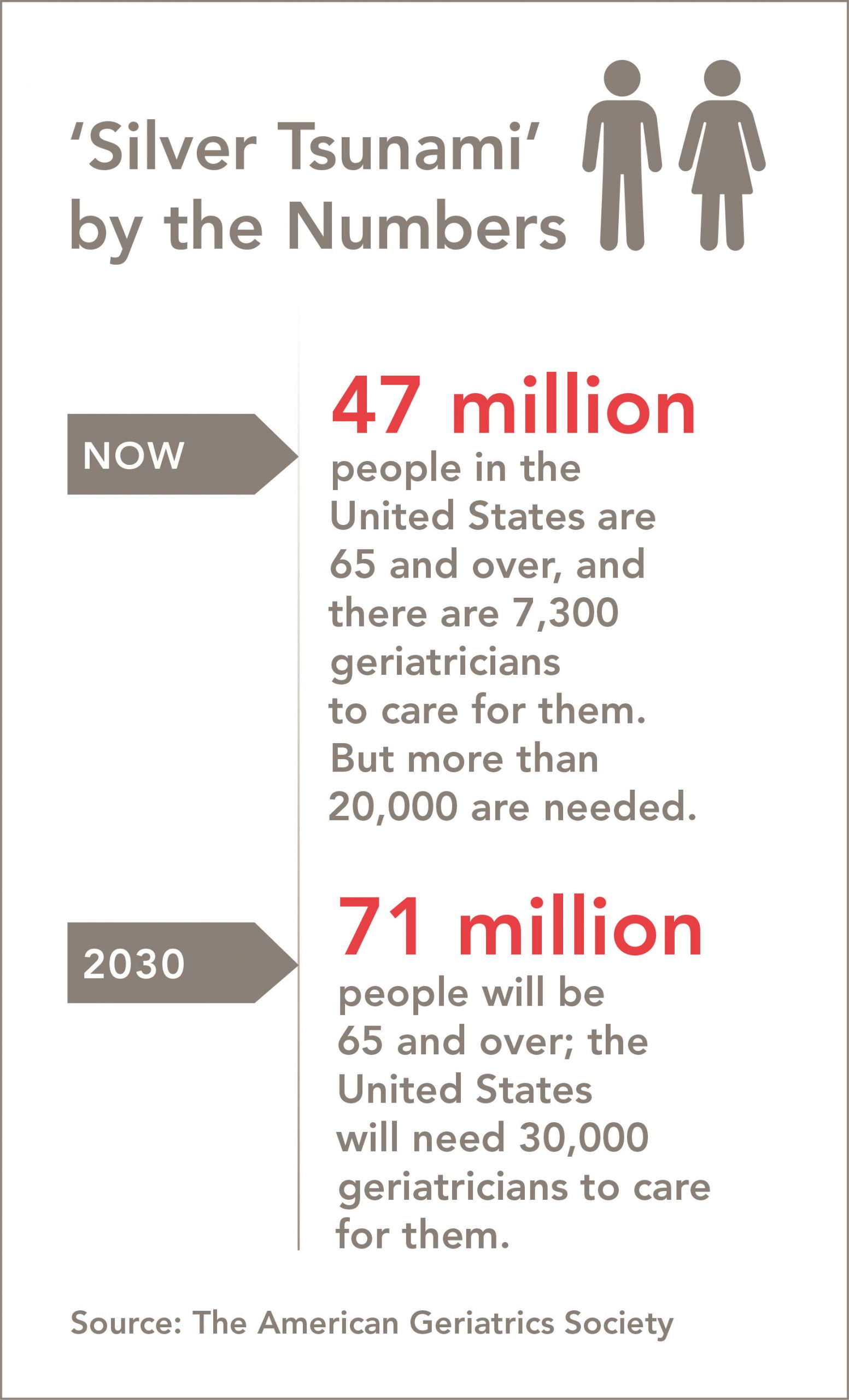

A wave of baby boomers: 10,000 Americans turn 65 every day.

A wave of baby boomers: 10,000 Americans turn 65 every day.

Because of the aging of the baby boom generation, 10,000 Americans turn 65 every day. The United States now has about 47 million people age 65 and over, and 7,300 geriatricians to care for them, but the American Geriatrics Society calculates that more than 20,000 are needed. By 2030—the high tide of the silver tsunami, when the 65-and-over population will total 71 million—the country will need 30,000 geriatricians, or four times the current number.

“When our students become practicing physicians, most will have many patients over 65,” says Joe Verghese, M.B.B.S., M.S., chief of geriatrics at Einstein and Montefiore and director of the Center for the Aging Brain, which provides integrated, comprehensive care for those suffering from memory loss, as well as social support for them and their caregivers. “It is enormously helpful for all students to receive geriatrics training, so they can provide the best care for their patients and their families.”

Geriatricians are trained to help elderly patients maintain their function and quality of life, often while coping with multiple chronic conditions, such as hypertension, heart disease, osteoporosis, arthritis, cancer, and diabetes. These experts can also care for people who are disabled, have dementia, or need end-of-life or palliative care. Geriatricians are trained not only in managing complex medical issues but also in the unique social, financial, and emotional needs and demands of the population.

According to Dr. Verghese, Montefiore’s geriatrics services reach about 3,000 patients per year in ambulatory-care clinics, inpatient services, and nursing homes. Recently developed satellite programs focusing on the brain and cognition, orthopedics, cardiology, and other initiatives reflect Einstein and Montefiore’s efforts to “geriatricize” clinical care and research throughout the Bronx, Westchester County, and New York State.

Einstein and Montefiore have created several programs to train the next generation of doctors in this grossly understaffed but highly rewarding specialty.

“Many medical students start off with a clear idea that they want to go into one of the more ‘glamorous’ specialties,” says Claudene George, M.D., M.S., an associate professor of medicine at Einstein and a geriatrician at Montefiore, who runs the geriatrics clerkship at Einstein. “But after their geriatrics clerkship experience, they learn to appreciate its importance.”

Einstein is among the one-third of medical schools that require students to take a geriatrics clerkship. The Einstein rotation immerses them in the fundamentals of geriatrics, including medication management; cognitive and behavioral disorders; patients’ self-care capacity; falls, balance, and gait disorders; and palliative medicine, which focuses on improving the quality of life for those who have serious illnesses or who are facing the end of life.

But it’s the interaction with patients and exposure to the field’s distinctive approach to care that can be transformative. Students regularly report that their experience in the diverse care settings is one of their favorite aspects of the rotation.

The geriatrics rotations occur at five sites in the Bronx and Westchester County. Depending on location, students engage in clinical care at inpatient, outpatient, home care, or nursing home settings. They emerge with specialized knowledge and skills: identifying medications that older people should avoid; differentiating among delirium, dementia, and depression; identifying hospitalization hazards for older adults; and learning about the unique financial and social challenges facing aging patients, including elder abuse and the assignment of medical proxies.

Susmit Tripathi, a fourth-year student at Einstein, recalls being won over by the idea of serving an aging population. He was particularly impressed with the coordinated care among providers, including physicians, nurses, nutritionists, and social workers—so different from the rigid hierarchies in some medical specialties.

He also believes the field is underappreciated and is confident that his exposure to geriatrics will give him a broader perspective. “Many of my colleagues at other schools have only a rough idea of what geriatrics is,” he says. In contrast, he is finishing a yearlong clinical research training program in neurology, with a focus on dementia and other issues of aging.

Claudene George, M.D., M.S. (standing), with patient Gertrude Williams and medical student Mallory Kerner-Rossi.

Claudene George, M.D., M.S. (standing), with patient Gertrude Williams and medical student Mallory Kerner-Rossi.

From left, Einstein students Luis Garza, Julia Kelly and Shombit Chaudhuri, with Myra Davila, M.D., and Calvary patient Celeste Reyes.

From left, Einstein students Luis Garza, Julia Kelly and Shombit Chaudhuri, with Myra Davila, M.D., and Calvary patient Celeste Reyes.

A highlight of the geriatrics clerkship is morning rounds at Calvary Hospital, one of the first (founded in 1899) and largest hospitals dedicated to palliative and hospice care. Calvary’s cheerful 225-bed facility in the Bronx is filled with plants and light. The hospital is within easy walking distance of Einstein and provides exceptional training in compassionate care for patients—most but not all of them elderly—who have advanced cancer or other life-limiting illnesses. Leading the students on morning rounds at Calvary is Einstein graduate Myra Davila, M.D., a clinical assistant professor of medicine at Einstein.

“I always say, ‘Death can be beautiful,’” says Dr. Davila when asked about working in a place where death is a regular occurrence. “It’s part of life. It doesn’t have to be sad, dark and out of your control. And it does not have to be painful. I think if people could see what we provide here it would change that perception.”

A native of the Bronx, Dr. Davila was attracted to Calvary and palliative care because of her experience at Einstein, where she completed the geriatrics rotation, took multiple geriatrics electives, was president of the student chapter of the American Geriatrics Society and was matched with Dr. Ehrlich as a mentor. (“‘You’re going to love geriatrics,’ she told me. She was right.”) She also completed the Montefiore-Einstein Geriatrics Fellowship Program. (See article below.)

“My geriatrics training was great, because you are not just consulting—you are on the front lines of healthcare,” Dr. Davila says. “It’s a huge myth that in geriatrics you only take care of demented old patients. For one thing, you become familiar with all the other medical specialties, but you learn to look at them as they pertain to caring for the older patient. And as a physician, you learn a whole other set of skills—including patience—that you can’t obtain anywhere else.”

Dr. Davila recalls that, as a medical student, she saw an elderly man who had lost a lot of weight. “We had assumed his weight loss was a health problem,” she says. Following the protocol learned during her geriatrics rotation, she sat with him and gently asked questions about his life and how he spent his days. Eventually, he revealed the real reason he wasn’t eating. “He was no longer able to buy groceries for himself, and he felt ashamed,” she recalls. “With that information, we were able to help him feed himself without subjecting him to medication or procedures that would not have solved the problem.”

Second-year medical student Emily Chase volunteers at Calvary on weekends through Project Kindness, an Einstein program in which medical students visit patients at local hospitals. For Ms. Chase and her fellow volunteers, it’s a chance to practice their communication skills and bedside manner, and to experience the satisfaction of making someone feel better. “It was great to meet the people you want to be helping and to make personal connections to them,” Ms. Chase says. Those weekly meetings with Calvary patients, she says, have reaffirmed her commitment to pursue geriatrics.

To become certified geriatricians, residents in internal medicine or family medicine must complete a geriatric medicine fellowship program. Among the nation’s oldest is the Montefiore-Einstein Geriatrics Fellowship Program, founded in 1983. The geriatrics faculty includes 13 full-time physicians plus specialists in geriatric nursing and social work. They typically fill all six fellowship positions each year, and have trained some 100 geriatricians.

The program trains physicians for careers in geriatrics in academic medical centers and clinical practice, says fellowship director Rubina A. Malik, M.D., an assistant professor of medicine at Einstein and a geriatrician at Montefiore. Many of them have gone on to become leaders in this burgeoning field. She notes that while the program has a long history, it’s always innovating, “offering areas of novel practices and teaching methods in the field of geriatrics,” and leveraging multidisciplinary approaches to enhance education.

The Palliative Care Program at Montefiore provides care and teaches students at several campuses. “The training in palliative care that we offer encompasses much more than clinical care,” says Peter Selwyn, M.D., M.P.H., chair of family and social medicine and director of the program. “To provide the best care, it’s important for medical students to learn about many different cultures and to approach each patient as an individual,” he says, citing a recent teaching moment with a large, multigenerational South Asian family whose matriarch required a ventilator and artificial feeding to live.

The medical team first assumed that such interventions would be detrimental to her quality of life, and the right path would be to withhold them. “But to the family,” Dr. Selwyn says, “it was the greatest gift and opportunity to honor her and give her total care, even though they recognized that she was not going to get better.”

Of the many methods Einstein-Montefiore clinicians use to teach end-of-life care, the most powerful may be their own example, which leaves a lifelong impression on students and patients.

Ms. Baumel, the patient we met at the beginning of this story, and her family have been under the care of Dr. Ehrlich and the Montefiore geriatrics and palliative-care teams for decades, starting with Ms. Baumel’s mother-in-law in the late 1980s. When Ms. Baumel’s husband, Abraham, died in January 2016, the nurses and social workers were there. Dr. Ehrlich also grieved with the family. “Not too many doctors visit the family when they sit shiva,” Ms. Baumel says. “She did.”

Asked to describe the quality of care the Baumel family has received from Montefiore, Ms. Baumel struggles to find the right words. “What comes above excellent?” she asks.