Nobody likes to be told to give up his or her favorite foods—least of all a child who feels perfectly fine. Just ask 12-year-old Juan Mendoza of the Bronx. Three years ago, during a routine checkup, blood tests revealed that Juan had abnormal liver enzymes signaling nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). It’s a condition in which fat silently accumulates in liver cells over many years. Unless Juan changed his diet and lost weight, he risked liver scarring and liver failure (cirrhosis) in the years ahead.

Juan was too young to appreciate the danger, but his mom, Maria Garcia, was alarmed. “I had never heard of fatty liver disease,” she says. “After looking it up on the Internet, I realized we had to visit the clinic.”

Ms. Garcia was referring to the Pediatric Fatty Liver Program at Children’s Hospital at Montefiore (CHAM), which opened in 2015 to care for the burgeoning population of children with NAFLD. The clinic is the only one of its kind in the Bronx and now follows about 300 patients a year—a number certain to increase.

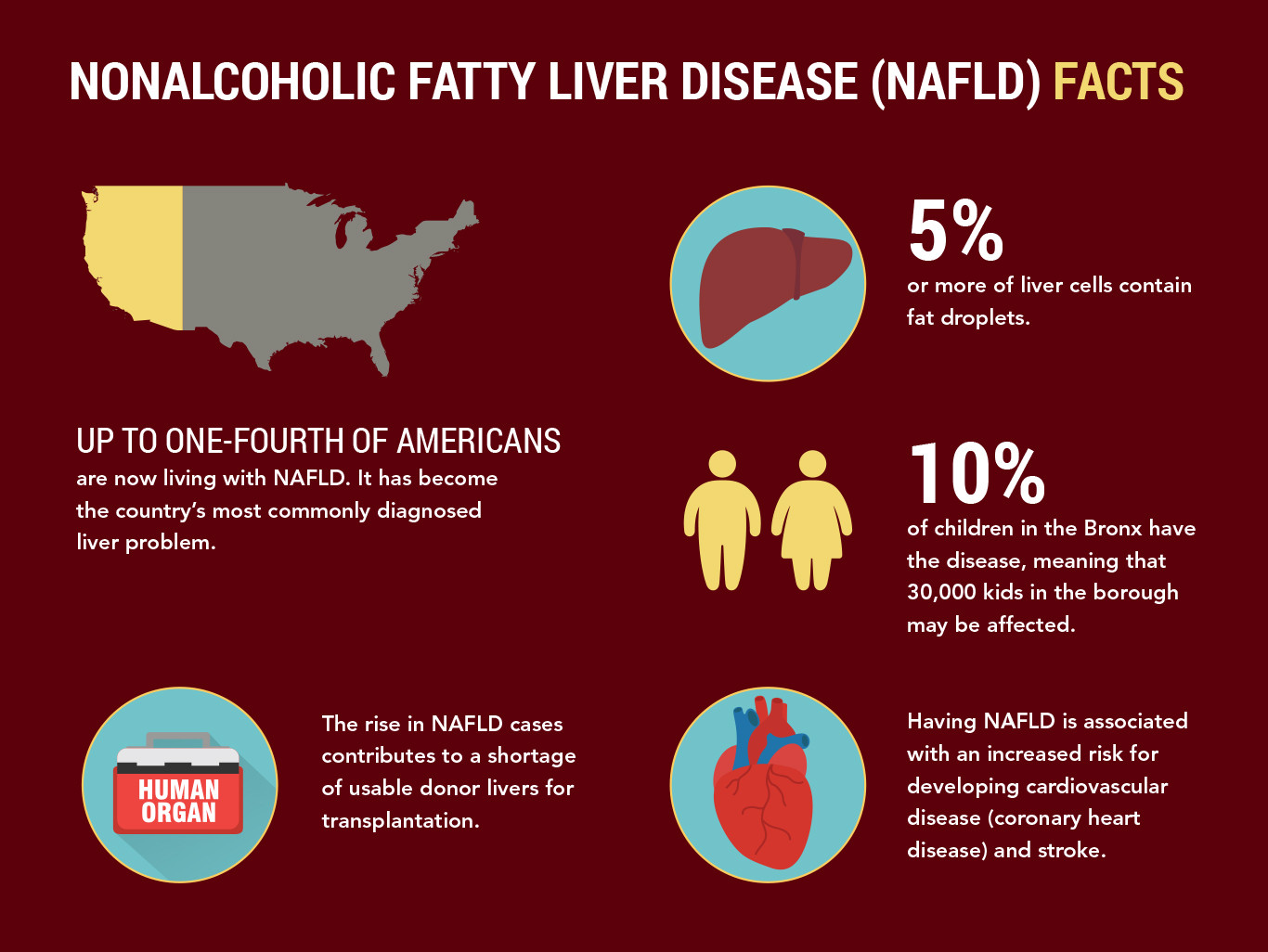

NAFLD wasn’t even described until 1980. Fueled largely by the obesity epidemic—one-third of Americans are now obese—it has become the country’s most commonly diagnosed liver problem. NAFLD affects people of all races and ethnicities but is most common in people of Hispanic origin, such as Juan. Up to one-fourth of Americans are now living with NAFLD, which is being diagnosed in children as young as 2. By some estimates, 10 percent of children have the disease, meaning that 30,000 kids in the Bronx may be affected.

“It’s a huge, silent epidemic,” says program director Bryan Rudolph, M.D., M.P.H., an attending physician in pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition at CHAM and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Einstein. “Many families are unaware of the disease and many pediatricians are not as worried about NAFLD as perhaps they should be. New professional-society guidelines call for kids to be screened for NAFLD between the ages of 9 and 12 if they are obese or are overweight and have additional risk factors. But the guidelines are not universally followed.”

At Juan’s first visit to the clinic, Dr. Rudolph performed tests to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other liver diseases. Currently, the only way to conclusively diagnose NAFLD is with a liver biopsy, in which a slender needle is inserted through the abdomen to retrieve a tiny sample of liver tissue. The invasive test is relatively safe and painless. (Young patients are sedated.) Juan’s mother vetoed a liver biopsy for her son, although she was eager to make sure that he changed his eating habits and got more exercise.

In the absence of drugs to treat NAFLD, low-calorie diets and exercise are the main interventions for people with the disease. Lowering cholesterol and triglyceride levels and, for people with diabetes, controlling blood sugar levels can also help.

Einstein-Montefiore researchers who study NAFLD include Victor Schuster, M.D. (see article, below), and Preeti Viswanathan, M.B.B.S., an attending pediatrician at CHAM and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Einstein. Dr. Viswanathan is investigating whether liver toxicity induced by acetaminophen (Tylenol) uses the same pathways as NAFLD. If so, therapies for the former might help in treating the latter.

Juan Mendoza, 12, walks with his mom, Maria Garcia, during a visit to the Pediatric Fatty Liver Program at Children’s Hospital at Montefiore.

Juan Mendoza, 12, walks with his mom, Maria Garcia, during a visit to the Pediatric Fatty Liver Program at Children’s Hospital at Montefiore.

Bryan Rudolph, M.D., and Rose M. Morales, C.P.N.P., examine Juan Mendoza.

Bryan Rudolph, M.D., and Rose M. Morales, C.P.N.P., examine Juan Mendoza.

One of the liver’s jobs is to store fat made from calories that the body doesn’t need right away. This stored fat (in the form of triglycerides) is typically burned to produce energy. But being overweight, having poor eating habits, getting too little exercise or having diabetes can cause triglycerides to accumulate in liver cells, leading to NAFLD. (Before NAFLD was discovered, fat accumulation in the liver was thought to be limited to people who drank large amounts of alcohol.)

For most patients, NAFLD progresses no further than having a fatty liver—a benign condition called steatosis. But steatosis sometimes goes rogue, with fat deposits inflaming liver cells and damaging the liver. This severe form of NAFLD, known as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), typically worsens over decades without causing symptoms.

NASH can ultimately lead to hepatic fibrosis (scarring of the liver) and, eventually, cirrhosis (liver failure) or liver cancer. NASH is now the third most common reason for liver transplantation and is predicted to rank as the number one reason by 2020.

Being overweight often works in tandem with genetics to cause NAFLD. Research over the past decade has highlighted the importance of PNPLA3, a gene involved in lipid metabolism. A variant of PNPLA3 increases the triglyceride (fat) content of liver cells and is especially common among Hispanics, perhaps explaining why NAFLD most often affects people of Hispanic origin.

People with the PNPLA3 variant have a greatly increased risk for developing NAFLD—but only if they’re also overweight. A 2017 study in Nature Genetics found that lean individuals—even those with two copies of the variant—face only a modestly increased risk for NAFLD and its complications compared with people who lack the variant.

People who have two copies of the PNPLA3 variant may benefit the most from modifying their lifestyles. A 2014 paper in the Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology described a controlled study involving 154 NAFLD patients placed on a regimen of exercise and reduced calories for one year. Compared with other patients, those patients with two copies of the PNPLA3 variant fared best with respect to several factors, including weight loss and greater reduction in their liver-cell fat content.

Given the increase in cases of NAFLD and the lack of therapies, scientists are searching for drugs that could prevent fat from accumulating in the liver. More than 200 trials of potential NAFLD drugs are ongoing, including several late-stage clinical trials. While it’s too early to tell whether any drug candidate will pass muster, one of the most intriguing is V2, a small molecule now under study at Einstein.

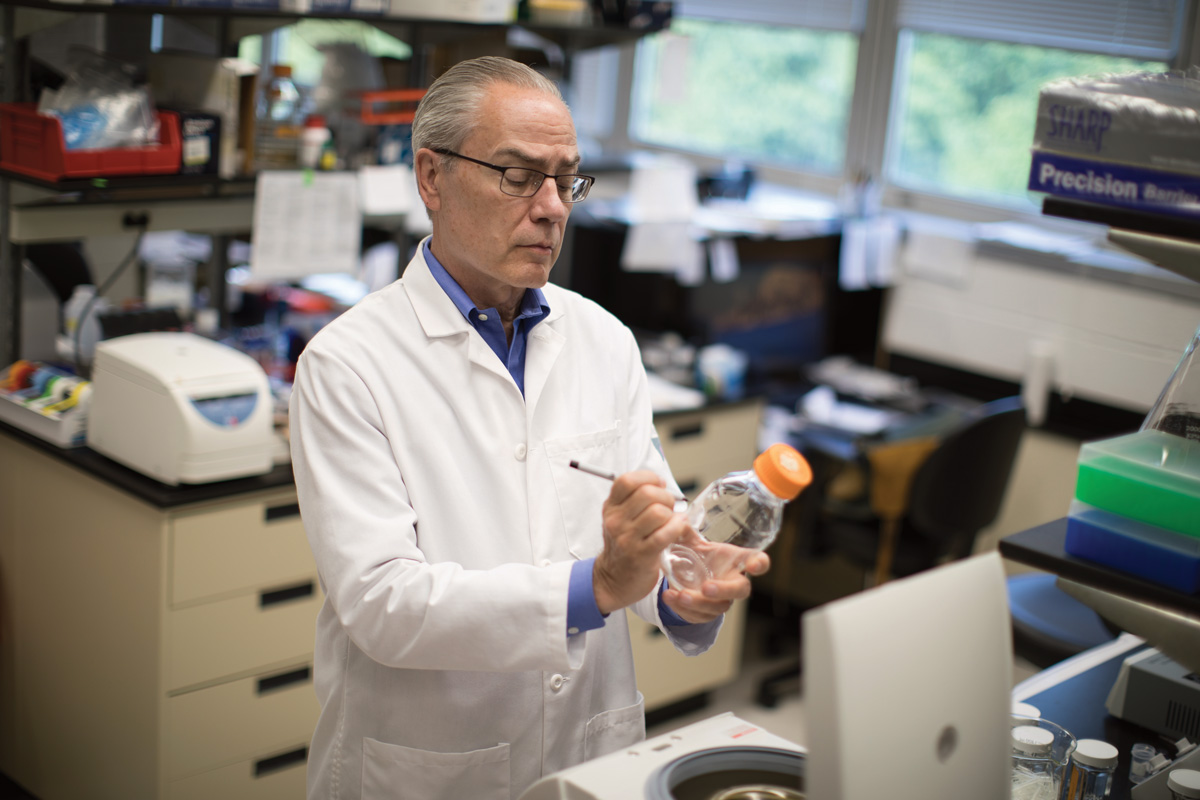

V2’s discovery involved some serendipity. Back in 1995, Victor Schuster, M.D., was looking for factors that regulate prostaglandins—signaling lipids that have various hormone-like effects, depending on where they are located in the body.

For example, prostaglandins found near peripheral blood vessels help dilate arteries and lower arterial pressure. While doing this research, Dr. Schuster discovered a protein, which he dubbed prostaglandin transporter (PGT), that regulates the uptake and metabolic clearance of prostaglandins in tissues throughout the body.

Fast-forward to 2015, when Dr. Schuster, the Ted and Florence Baumritter Chair in Medicine and a professor of medicine, wanted to learn more about what PGT molecules do. He successfully created PGT “knockout” mice that lived to adulthood despite lacking the PGT gene. As expected, the knockout mice had no trace of PGT protein anywhere in their bodies.

“To our surprise, the PGT-free mice had one-third the body fat of normal mice, even while consuming twice as much food,” the researcher says. “Usually, excess calories have to go somewhere, and they often get parked in the liver. But their liver cells were completely spared.”

The mice appeared to be healthy overall, and actually lived longer than normal mice.

Dr. Schuster is at a loss to explain why the absence of PGT—which performs critical functions throughout the body—wouldn’t harm the animals. Yet people also can survive without it: The medical literature describes some 140 humans who are missing one or both copies of the PGT gene.

“For the most part they’re fine, suggesting that if we can find a drug that blocks PGT in people, we’ll have a safe way to treat NAFLD,” he says. “Furthermore, we are aiming to block PGT only in liver cells, which should make it even safer.”

By screening libraries of drug compounds, Dr. Schuster found a few that had an affinity for PGT. Unfortunately, all were large compounds, which the gastrointestinal tract generally has trouble absorbing into the bloodstream.

Enter Einstein’s Evripidis Gavathiotis, Ph.D., an associate professor of biochemistry and of medicine and a drug-design expert. Using in silico (computer-based) modeling, which can predict how substances will interact based on their molecular structures, Dr. Gavathiotis came up with 100 novel potential anti-PGT compounds, one of which—dubbed V2—showed the most promise in tissue-culture studies. Dr. Schuster says it’s the only potential NALFD drug that targets PGT.

Dr. Schuster and his colleagues are now testing the safety and efficacy of V2 and related molecules in a mouse model of NAFLD. His work is supported by a 2018 Scholar-Innovator Award from the Harrington Discovery Institute in Cleveland.

Victor Schuster, M.D., and colleagues are testing the safety and effectiveness of compounds that target a protein involved in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Victor Schuster, M.D., and colleagues are testing the safety and effectiveness of compounds that target a protein involved in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.