In mid-March 2020, just two weeks after the first COVID-19 case was detected in New York State, patients began flooding into Montefiore Medical Center’s intensive care unit (ICU), triggering anxiety throughout the hospital. No one had seen anything like this, not even at the height of the AIDS epidemic a generation earlier.

“We started doing projections about what to expect in the days ahead,” says Michelle Ng Gong, M.D., M.S., chief of the divisions of pulmonary medicine and of critical care at Montefiore and Einstein and professor of medicine and of epidemiology & population health at Einstein. “The worst-case scenario was that we had to prepare for 600 ICU patients at once—six times our normal capacity. Basically, we would have to turn the entire hospital into an ICU.”

With the administration’s support, Dr. Gong began planning for a supersized ICU. And then things went from bad to worse. A week after treating her first coronavirus patient, Dr. Gong came down with a fever, body aches, and fatigue. She didn’t need a nasal-swab test to know the diagnosis.

“My biggest worry was about infecting my family,” Dr. Gong says. “I had already kicked my husband out of our bedroom by that time, and I had my own bathroom. But we live in an apartment, and everyone got sick.” (She, her husband, and her two teenage sons have since recovered.)

Fortified with acetaminophen and ibuprofen, Dr. Gong set up shop at home, remotely orchestrating Montefiore’s efforts to scale up its ICU and consulting with clinical colleagues on the front lines. Her tasks included building a central command center where her staff could monitor and direct care for hundreds of critically ill patients on three different campuses.

“Given the limited size of our critical-care staff, there was no other way to manage it all,” she says. Ten days later, the center—with links to every ICU bedside and nursing station—was up and running in the Binswanger Auditorium on Montefiore’s ground floor. “It didn’t matter that I was sick,” says Dr. Gong, whose fever persisted for 10 days. “Patients were rolling in nonstop. If we didn’t set up the command center, many more patients were going to die.”

We were very challenged, but we were never overwhelmed.

—Dr. Michelle Gong

Meanwhile, Dr. Gong recruited “everybody under the sun” to take care of patients: anesthesiologists, pediatric neurologists, cardiologists, otolaryngologists, endocrinologists, rheumatologists, gastroenterologists, and psychiatrists. Anyone who wasn’t well versed in critical care soon would be. Dr. Gong returned to Montefiore after 13 days away, just as the hospital’s COVID-19 caseload was peaking.

Somehow, she and her staff found time to initiate clinical trials to evaluate three promising coronavirus medications. “Doing research is very challenging when patients are so critically ill,” she says. “But we needed to find better treatments, not just for our patients but also for those in states and countries where the pandemic was just emerging. Not to have learned anything from all the lives lost in this city would be an even bigger tragedy.”

Dr. Gong drew on her decades of experience participating in and leading clinical trials, several focused on preventing acute respiratory distress, the death knell for many COVID-19 patients. In a case of perfect timing, in early March she’d gone to Washington, D.C., for an international meeting of critical-care physicians. A hot topic of conversation: how to conduct research in the midst of a pandemic.

Practicing medicine in an entirely new environment posed challenges. “We got used to the physical inconveniences—the facial rashes and headaches from constantly wearing masks,” Dr. Gong says. “What was worse was having to keep patients’ loved ones away. Many of our care decisions depend on family meetings, and those had to be done using apps like FaceTime.”

The intensity of the work took its toll, as days blurred into weeks and more and more staff members fell ill with the very virus they were trying to quell. In late April, the pandemic’s emotional price was brought to the fore by news that a NewYork-Presbyterian emergency room physician had killed herself. “It hurt to the core,” Dr. Gong says.

I hope by the end of this pandemic we’ll know a lot more about how to handle the next one.

— Dr. Michelle Gong

To counter the gloom and doom, members of the department of psychiatry were invited to join staff meetings and lend support. Staffers who were sickened by COVID-19 but had recuperated and rejoined the battle were awarded “purple pins” decorated with an image of the coronavirus and the word “recovered.” Nurses called out “happy codes” over the intercoms to celebrate patients weaned from ventilators—an antidote to the relentless “rapid response” codes alerting the staff to patients in distress.

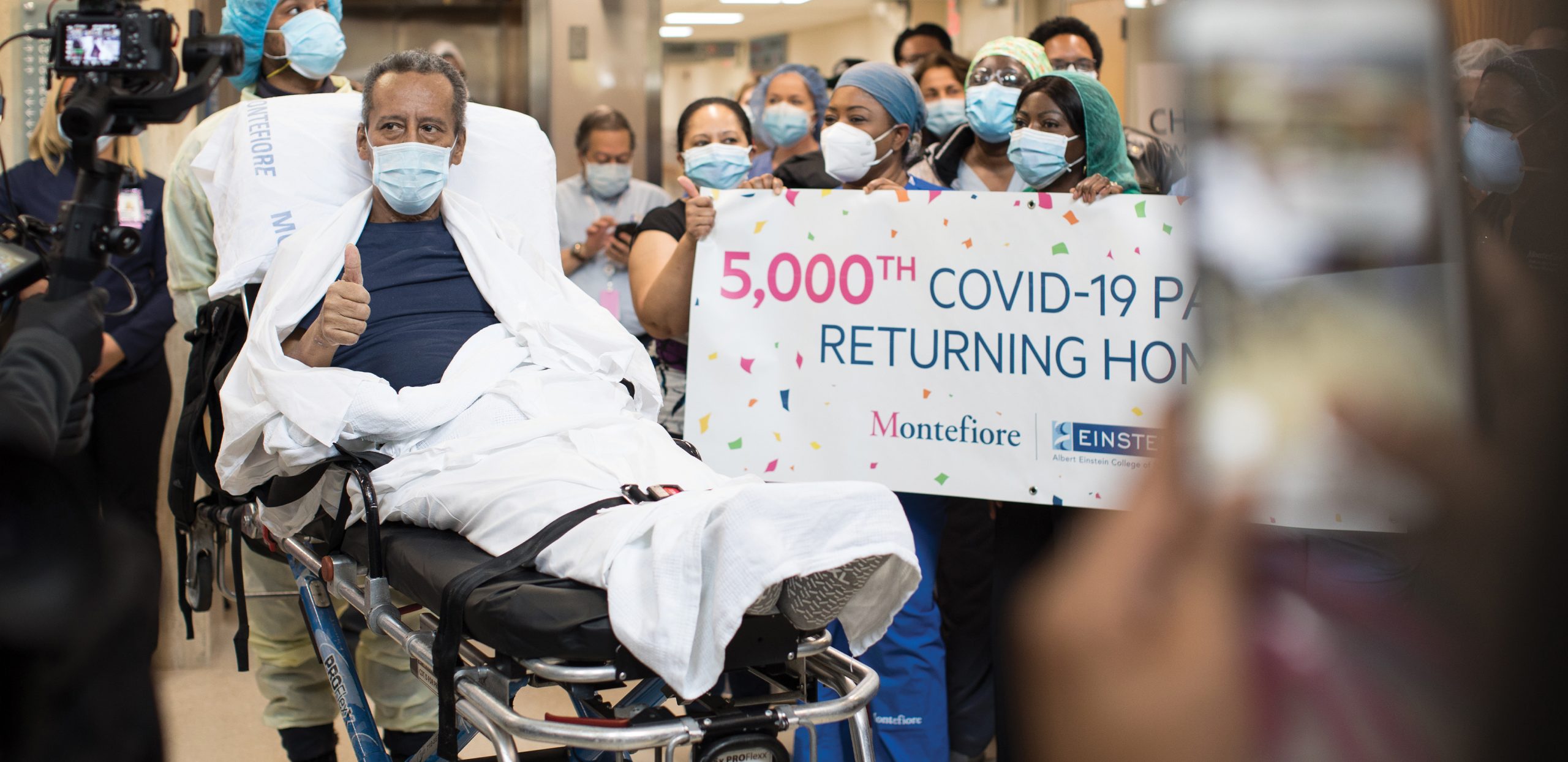

The number of patients in the ICU at the Moses campus finally crested at 300 in late April, a welcome relief to Montefiore’s beleaguered staff. “We were very challenged, but we were never overwhelmed,” Dr. Gong says. “At every stage, we were able to escalate our resources to meet the needs of patients.”

In May Dr. Gong and her team were the subject of an hour-long CBS News special documentary, “Bravery and Hope: Seven Days on the Front Line” (see below). In June she was given the Museum of the City of New York’s Gotham Icon Award for her “heroism, selflessness, and amazing leadership” during the pandemic.

Dr. Gong doesn’t want to be portrayed as the hero in this story. “I can’t give enough credit to everybody who stepped up during this crisis: the administrators, the doctors, the nurses,” she says. “It’s so life-affirming, their dedication and selflessness. There were so many heartwarming stories, like the one of the husband and wife who were hospitalized with COVID-19 at the same time, and the nurse who arranged for them to share a room. Simple, little things like that really meant a lot.”

To Dr. Gong, the biggest heroes were her critical-care and pulmonary medicine fellows. “These folks are still in training, yet they were so skilled in responding to emergencies,” she says. “They functioned like full attending physicians and never lost their cool.”

Asked to sum up what was learned from the crisis, Dr. Gong says: “I think we’ve learned a lot. We’ve learned how to mobilize a large system. We’ve learned how difficult it is to communicate across a large hospital—that’s something we need to improve on. I hope that by the end of this pandemic we’ll know a lot more about how to handle the next one.”

The past few months have been a bit of a blur for Yaron Tomer, M.D., but one date in particular stands out: March 24, 2020. “That day, our population health experts informed us that, at current admission rates, our health system would soon be overwhelmed with COVID-19 cases, and we wouldn’t have enough doctors, nurses, ventilators, or protective equipment to properly care for every patient with the disease,” recalls Dr. Tomer, who is the chair of medicine at Einstein and Montefiore and a professor of medicine and of microbiology & immunology and the Anita and Jack Saltz Chair in Diabetes Research at Einstein.

Adding to his concern, March 24 was also when Dr. Tomer was diagnosed with COVID-19. “My wife, son, and daughter also tested positive,” he says. “We all came down with a mild fever and back pain and temporarily lost our sense of smell. But given what I’ve seen in the hospital, we were extremely lucky.”

In the last week of March, more than 650 COVID-19 patients were admitted to Montefiore Health System, and the numbers were increasing exponentially. To make things worse, critical-care director Michelle Gong, M.D., was already sickened by COVID-19. That meant that two of Montefiore’s top physicians were quarantined and working remotely during this crucial week—far from ideal for a hospital facing the largest crisis in its 138-year history. Fortunately, before the pandemic reached the Bronx, Dr. Tomer had devised and implemented a “Three C Teamwork” plan for handling the crisis: coordination, communication, and collaboration.

In a nutshell, his approach aimed to ensure that his thousand-member department of medicine (DOM), by far the hospital’s largest, coordinated its COVID-19 efforts, that leadership communicated with frontline staff, and that the department collaborated with other parts of the health system.

To achieve the first C—coordination—Dr. Tomer assembled a departmental COVID-19 task force, consisting of 18 representatives from all arms of the DOM. The task force convened every morning via conference call for weeks.

Communication was achieved through a daily electronic newsletter—a potpourri of news and information about COVID-19 treatment protocols and clinical trials, links to salient papers, useful resources such as housing and parking information, and statistics on how the hospital was handling the pandemic. “My motto was that whatever I know about COVID-19 at Montefiore, everybody should know,” Dr. Tomer says.

More than 7,000 staff members and alumni received the newsletter, as did a sizable number of outside clinicians and hospital administrators. In addition, the department’s treatment protocols were disseminated through an online folder and a smartphone app. “Those tools were constantly updated with the latest guidelines, and this improved outcomes,” Dr. Tomer says.

Collaboration involved the entire medical center. “COVID-19 is a medical disease, but we couldn’t double the size of our medical service and triple the size of our intensive-care units without help from departments throughout the hospital,” he says. “We did not do anything alone.

Montefiore’s frontline workers were anxious about becoming infected and bringing the virus home to family members, and rightly so—nearly one in five residents tested positive for COVID-19. But they had an even bigger concern. “As I met with the hospital’s doctors and nurses,” Dr. Tomer says, “their number one worry was that we’d have to ration healthcare, as had happened in Europe. They were asking, ‘Will we have to decide who gets admitted to the hospital, or who will get a ventilator? Will we have to make such decisions?’”

It didn’t come to that, thanks to New York City’s lockdown and social-distancing measures, which gradually flattened the curve of the pandemic, and because Montefiore’s clinicians got better at managing patients.

“COVID-19 is not like any disease we have seen before,” Dr. Tomer says. “This is not just a serious viral pneumonia that sometimes affects other organ systems. This virus directly harms almost every system in the body, including the lungs, the heart, the brain, and the intestines. While we couldn’t get rid of the virus, we learned that we could save lives by taking care of the complications and giving the immune system time to clear the virus.”

This virus directly harms almost every system in the body.

— Dr. Yaron Tomer

Montefiore physicians were directly responsible for several COVID-19 clinical advances. One example was the use of steroids to quell the often-fatal inflammation caused by the immune system’s overzealous response to infection.

“The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and two medical societies had warned against using steroids in COVID-19 patients, based on their harmful effects in SARS patients,” Dr. Tomer says, referring to the coronavirus that plagued China in the early 2000s. “But one of our attendings, Shitij Arora, M.B.B.S., had a patient who was doing very poorly, and he gave her steroids as a last resort. The patient recovered. Dr. Arora subsequently tried it on four other critically ill patients, and all responded.”

Dr. Tomer and his team concluded that steroids such as prednisone were beneficial for COVID-19 patients with low oxygen levels and signs of severe inflammation. So in early April they issued a new steroid-treatment protocol, which was communicated throughout Montefiore and to other institutions.

“We now know from a large clinical trial in the United Kingdom that we did the right thing,” Dr. Tomer says. “That trial found that dexamethasone, another steroid drug, reduces mortality by 20% to 30% in patients.” Montefiore’s own study during the pandemic found that steroids reduce mortality by nearly 80% in COVID-19 patients with the highest level of inflammation.

Montefiore physicians also devised and disseminated COVID-19 protocols for the treatment of potentially deadly blood clots and for ketoacidosis, a severe complication of diabetes seen frequently in COVID-19 patients.

COVID-19 has highlighted certain strengths of the healthcare system—its ability to adapt quickly when confronted by a new and catastrophic disease, for example—but also revealed glaring weaknesses, such as racial disparities in health outcomes.

“I think the level of care that people got here in the Bronx wasn’t any different than in other regions,” Dr. Tomer says. “If anything, it was superior. But the Bronx was hit particularly hard by the pandemic, with Blacks and Latinx hospitalized at nearly twice the rate of whites. One reason is the inadequate access to care for chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease—major risk factors for becoming severely ill or dying from COVID-19.

“If there’s anything good that can come from this,” he adds, “I hope the pandemic emphasizes the urgent need to eliminate the health disparities that have existed for decades, if not centuries.”

Now that this pandemic seems to be easing, at least in New York, Dr. Tomer is already thinking about and preparing for the next one. “The main lesson from COVID-19 is to let the scientists, not the politicians, lead the response to epidemics,” he says. “Public health and individual health should take precedence over everything else.”

A second lesson is the need to plan ahead, just as we do for nuclear disasters and earthquakes. “For pandemics,” Dr. Tomer says, “I would recommend a plan for storing and distributing personal protective equipment, and for developing capabilities for creating test kits that can be mass-produced quickly. We also need to establish the infrastructure needed for rapidly manufacturing vaccines against known and emerging pathogens. Pandemics are no longer a once-every-hundred-years phenomenon, but instead can be expected every 10 or 20 years, and we need to plan accordingly.”

In addition, many survivors of COVID-19 will still need help. “We have to address the challenges faced by thousands of patients who’ve recovered from COVID-19 but are still suffering from complications,” Dr. Tomer says. “So we’ve created our COVID-19 Recovery Clinic, where they can be cared for by a multidisciplinary team of experts.”

Dr. Tomer has also been thinking about the future of postpandemic medical education. “Since physician training is taught at the bedside, it will probably change less than other aspects of healthcare,” he says. “There will certainly be more remote and virtual learning, but mastering the key aspects of care—speaking to patients, examining and diagnosing them—cannot be simulated by any program or machine. That’s why I and so many others became doctors in the first place, for those human interactions. That’s the beauty of medicine.”

Kartik Chandran, Ph.D., feared this day would come. “After the SARS, MERS, and H1N1 virus-caused outbreaks, it seemed only a matter of time until we had a global viral pandemic,” he says. “The only questions were what agent would cause it and under what circumstances.”

During his years of doctoral and postdoctoral training, Dr. Chandran had mastered the skills for succeeding in academic research, from designing experiments to writing grants to publishing papers. Now he needed to learn how to run a lab from home—in the middle of a pandemic he had known was inevitable.

For Dr. Chandran, professor of microbiology & immunology and the Harold and Muriel Block Faculty Scholar in Virology at Einstein, the connection to COVID-19 began in late January, when the first cases of COVID-19 were reported in the United States. “At the time, government leaders and public health officials were giving mixed messages about COVID-19, saying it was similar to the flu,” he recalls. But as a virologist who works with some of nature’s most notorious pathogens, he wasn’t persuaded.

“People were immunologically naïve to the virus responsible for COVID-19 and therefore had no real protection against infection,” he notes. In late February, when the first cases of community spread came to light, he and his wife began to socially distance from neighbors and friends and to stockpile supplies for a lengthy stay in their Brooklyn home. They withdrew their son from his private school and helped persuade its administrators to shut it down before it had a single case, weeks before public schools in the city did the same.

“For my lab, the signal moment was the third week of February, when several of us were supposed to go to a conference in San Diego,” he continues. “I cancelled our travel plans. A week later, I told my staff that I would be working from home and that they could do so as well.”

Socially distanced but electronically connected, Dr. Chandran began collaborating on a variety of COVID-19 studies. “Most of the work was done by my ‘COVID Crew’—the students in my lab who went in to work on all the COVID-19 projects,” Dr. Chandran says. (See “Graduate Students Create Antibody Test.”)

The first priority was an urgently needed antibody test. Montefiore was using convalescent plasma (obtained from patients who’d recovered from COVID-19) as a treatment for the disease and needed a test to ensure that donated plasma was rich in antibodies. (See “Old Treatment Takes On a New Pandemic,” below.)

Such a test would also allow Montefiore to determine whether staff members exposed to the virus had mounted an immune response and might therefore safely be able to return to work. And an in-house test would increase testing capacity and provide backup in case commercial antibody tests were found to have problems.

The antibody test developed by Dr. Chandran, Jonathan Lai, Ph.D., and their teams looks specifically for antibodies against the virus’s spike proteins, which protrude from the viral surface and enable the virus to infect human cells. (Dr. Lai is a professor of biochemistry at Einstein.)

People were immunologically naïve and had no real protection.

— Dr. Kartik Chandran

You’ve heard of a “wolf in sheep’s clothing.” Dr. Chandran’s team created the opposite: a “sheep in wolf’s clothing” virus that behaves just as the novel coronavirus does but is much safer for scientists to study in the lab.

The coronavirus infects cells via its surface spike proteins, which enable the virus to latch onto and enter cells. Dr. Chandran and his colleague Rohit Jangra, Ph.D., research assistant professor, transferred the coronavirus spike-protein gene into a relatively harmless virus called vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), causing spikes to sprout from VSV’s surface.

By infecting cells in precisely the way the coronavirus does, this safer, genetically engineered version could help scientists develop drugs that block infection and protect against disease.

“Other groups around the country have sequenced the coronavirus, but not here in the Bronx,” Dr. Chandran says. “The genetics of SARS-CoV-2—the official name of the novel coronavirus—is constantly evolving, and it’s conceivable that we could learn something new about it from the strains circulating here. Our preliminary data suggest that the virus arrived in the Bronx from all over the world, not just from the West Coast of the United States or from China, which tells us something about the epidemiology of the disease.” Dr. Chandran’s team is analyzing the antibodies of dozens of recovered COVID-19 patients who will provide blood samples at regular intervals for up to a year.

In potentially his most consequential COVID-19 project, Dr. Chandran is developing a monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy for COVID-19 patients. It’s a turbocharged version of convalescent-plasma therapy.

Convalescent plasma contains many different antibodies against the coronavirus, some of which neutralize it much better than others. Monoclonal antibody therapy is much more focused: the result of screening plasma from hundreds of recovered COVID-19 patients, finding the one or two antibodies that do the best job of neutralizing the coronavirus, and then manufacturing those antibodies in great quantities.

As part of the Prometheus Consortium—five institutions collaborating to develop antibody-based therapies against viruses—Dr. Chandran’s team has evaluated hundreds of antibody candidates and identified several that powerfully neutralize SARS-CoV-2.

Find out how the antibody test was created, and learn more about the surrogate coronavirus.

Get up-to-date coverage of Einstein and Montefiore’s response to COVID-19.

Early in the pandemic, as doctors scrambled to find some way to treat patients infected by the novel coronavirus, Liise-anne Pirofski, M.D., chief of infectious diseases at Einstein and Montefiore, had a eureka moment.

“For my entire medical career, I’ve been interested in antibodies and how they bolster the immune response,” recalls Dr. Pirofski, who is also a professor of medicine and of microbiology & immunology and the Selma and Dr. Jacques Mitrani Chair in Biomedical Research.

“Studying art history in college, I was particularly intrigued by medically related images, such as renditions of the dance of death and of people ravaged by plague. COVID-19 conjured up thoughts of antibodies, plagues, and convalescent plasma, which had shown promise against pandemic plagues such as influenza and SARS. Historic uses of convalescent plasma led to a Journal of Clinical Investigation [JCI] article, which helped kick everything off,” she says.

Plasma, or sera, is what remains when red and white cells are removed from blood: a yellowish liquid containing water, salt, enzymes, and antibodies. Convalescent plasma is taken from people who have recovered from an infection and then transfused into patients suffering from the same infection. In contrast to vaccination, convalescent plasma could offer immediate immunity by providing antibodies that patients need to fight off microbial infections.

Dr. Pirofski collaborated on the JCI article with her longtime Einstein colleague Arturo Casadevall, M.D., Ph.D., who now chairs the department of molecular microbiology and immunology at Johns Hopkins. Their widely publicized article, published March 13, alerted the world to convalescent plasma—an old and all-but-forgotten therapy with the potential for saving lives today.

“We recommend that institutions consider the emergency use of convalescent [plasma] and begin preparations as soon as possible. Time is of the essence,” Drs. Pirofski and Casadevall wrote in JCI. “In the early 20th century, convalescent [plasma] was used to stem outbreaks of viral diseases such as poliomyelitis, measles, mumps, and influenza,” the authors wrote, noting that the therapy fell out of favor with the advent of antimicrobial therapy in the 1940s but never completely disappeared. It recently showed promise against two other coronavirus-caused outbreaks (SARS1 in 2003 and MERS in 2012), as well as the 2013 West African Ebola epidemic.

“Although every viral disease and epidemic is different, these experiences provide important historical precedents that are both reassuring and useful as humanity now confronts the COVID-19 epidemic,” the researchers added.

COVID-19 conjured up thoughts of antibodies, plagues, and convalescent plasma.

— Dr. Liise-anne Pirofski

“The pandemic allowed me to study the effectiveness of antibodies in people,” Dr. Pirofski says. But her first priority was trying to make convalescent plasma available to the many patients for whom it might mean the difference between life and death.

By late March, a national convalescent plasma advisory group (led by Dr. Casadevall and the Mayo Clinic’s Michael Joyner, M.D., and including Dr. Pirofski) had convinced the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to designate convalescent plasma as an investigational new drug, allowing physicians to administer it to seriously ill COVID-19 patients on a “compassionate use” basis outside clinical trials.

The resulting U.S. Convalescent Plasma Expanded Access Program has proven extremely popular. As of late August, the program had administered plasma to more than 70,000 patients nationwide. In a call with governors on August 3, U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex M. Azar II said that demand for plasma was exceeding the supply.

Dr. Pirofski directed the expanded-access program at Montefiore along with co-investigator Hyun Ah Yoon, M.D., and was part of its national leadership group. They treated 103 severely ill COVID-19 patients at Montefiore with convalescent plasma and compared their outcomes to those of patients in a retrospective control group. The study, now being reviewed for publication, found that convalescent plasma appeared helpful, especially for younger patients treated early in the course of the disease—a confirmation of past experiences with the therapy.

Other researchers recently published a “safety update” on the program’s first 20,000 patients treated under the expanded-access program. “That study showed that convalescent plasma is very safe, with an incidence of serious adverse effects similar to standard plasma used in hospitals every day,” Dr. Pirofski says.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are medicine’s gold standard: the only way to conclusively show whether a therapy is effective. Despite its more than 100 years of use, convalescent plasma for a pandemic disease has never been evaluated in large RCTs; hence the importance of establishing its effectiveness against COVID-19. Helpful though it may be, the expanded-access program lacked the necessary control group. Dr. Pirofski wanted to settle the matter once and for all.

On April 17, she helped launch a convalescent-plasma RCT involving Einstein-Montefiore, NYU Langone Medical Center, and the Yale University School of Medicine, a group that has recently been expanded to include the University of Miami and the University of Texas–Houston. The Einstein-Montefiore study was launched with a $300,000 gift from the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Foundation and $200,000 in emergency funding from Montefiore Health System; Dr. Pirofski, along with Marla Keller, M.D., later received a $4.3 million National Institutes of Health grant to support the trial.

Plans for the Einstein-Montefiore trial called for studying 300 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who had respiratory signs and symptoms, half to receive convalescent plasma and the other half a placebo. But recently, recruitment has fallen off. Success in controlling the pandemic in the area has reduced the number of patients who qualify. As of mid-August, 185 patients had been enrolled in New York City and the Bronx.

It’s a national problem as well: other RCTs evaluating convalescent plasma in the United States have so far recruited fewer patients than expected as the pandemic has moved to new areas.

To gain insight into plasma’s possible effectiveness, Dr. Pirofski and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis on data pooled from 12 RCTs and other studies from around the world, involving a total of 804 patients. Their study, posted as a preprint on July 30 to medRxiv, found that convalescent plasma reduced mortality rates for patients treated with it by 57% compared with those for untreated patients.

Meanwhile, in an approach described recently in JAMA, other researchers plan to continuously pool and monitor data being generated by at least 10 incomplete and still-active RCTs. “It requires some innovative statistical techniques, but this project has the potential for reaching scientifically valid conclusions about plasma once enough data have been collected,” Dr. Pirofski says.

What gives me hope is that we have the ability to make things better for people.

— Dr. Liise-anne Pirofski

What will be the verdict? “Everything we’ve learned so far indicates that convalescent plasma is safe—certainly no riskier than a blood transfusion,” says Dr. Pirofski. “As for effectiveness, we won’t know for sure until the RCTs have spoken—which I hope will happen soon.”

The need for an effective COVID-19 treatment—and for health improvements in general—is especially urgent in the Bronx, Dr. Pirofski says. “For far too long, the health of poor communities has not received sufficient recognition or resources,” she says. “Here in the Bronx, we see how this has led to the pandemic’s devastating effect on Hispanics and African Americans, due mainly to underlying health conditions that have gone untreated. What gives me hope is that, as physicians and scientists, we have the ability to make things better for people in these communities and alleviate some of the suffering.”

For Dr. Pirofski, the COVID-19 pandemic has echoes of her experience more than 30 years ago, as a young resident on a Bellevue Hospital ward where more than a quarter of the patients were suffering from AIDS. “Taking care of those patients was a devastating experience,” she recalls. “There was the same helpless feeling of being overwhelmed, of patients with labored breathing withering away and dying because we couldn’t change the course of their disease.

“But compared with AIDS back then,” she continues, “we’ve known about COVID-19 for a very short time—only about eight months—and yet we’ve learned much more about how COVID-19 occurs and how it’s transmitted, and we’re taking better care of our patients.”