Two of them had been studying Ebola infection. Another was working on mosquito- and tick-borne diseases. But last March, all three Einstein graduate students quickly switched gears to tackle a different bug. Within weeks they were playing key roles in creating an antibody test for the novel coronavirus.

The antibody test was crucial for determining whether people had been previously infected and for evaluating whether serum from recovered patients could effectively treat patients ill with COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus.

Ryan Malonis, a sixth-year M.D./Ph.D. candidate, hit the ground running: His work on chikungunya virus, which is transmitted by mosquitoes, uses some of the same technology needed to develop a coronavirus antibody test.

“This brand-new coronavirus was devastating the community around us, and very little was known about how it worked,” he says. “As infectious-disease researchers, we felt a sense of duty to be a part of this effort.” Mr. Malonis was working in the Michael F. Price Center for Genetic and Translational Medicine/Harold and Muriel Block Research Pavilion in the lab of Jonathan Lai, Ph.D., professor of biochemistry at Einstein.

Across Morris Park Avenue in the Samuel H. and Rachel Golding Building, Ariel Wirchnianski was developing antibody therapies against the Ebola virus in the labs of Dr. Lai and Kartik Chandran, Ph.D., professor of microbiology & immunology and the Harold and Muriel Block Faculty Scholar in Virology at Einstein. “Our labs have a lot of tools that we can use to study different viruses,” says Ms. Wirchnianski, a sixth-year Ph.D. candidate. “If we could apply them to this new virus, and we could make some small difference in combating this pandemic, we wanted to try.”

Robert Bortz, a sixth-year M.D./Ph.D. candidate and Ms. Wirchnianski’s colleague in the Chandran lab, agrees with her. “Kartik asked who was available and willing to come in to build this diagnostic test, given that we had a limited number of people who could be in the lab, to maintain social distancing,” he says. “As someone deeply interested in virology research, I was eager to help.”

Members of the Lai and Chandran labs first determined how best to coordinate their efforts to develop the antibody test. “It was, ‘We’ll do this, we’ll hand it off to you, and then you will do that,’” Mr. Malonis says. His own role involved making large quantities of the coronavirus’s spike protein, which the coronavirus uses to infect human cells; antibodies that do the best job of protecting against infection are those our immune systems make against these proteins. Dr. Lai explains: “Our test would use the spike protein like bait, to detect those antibodies from a patient’s serum.”

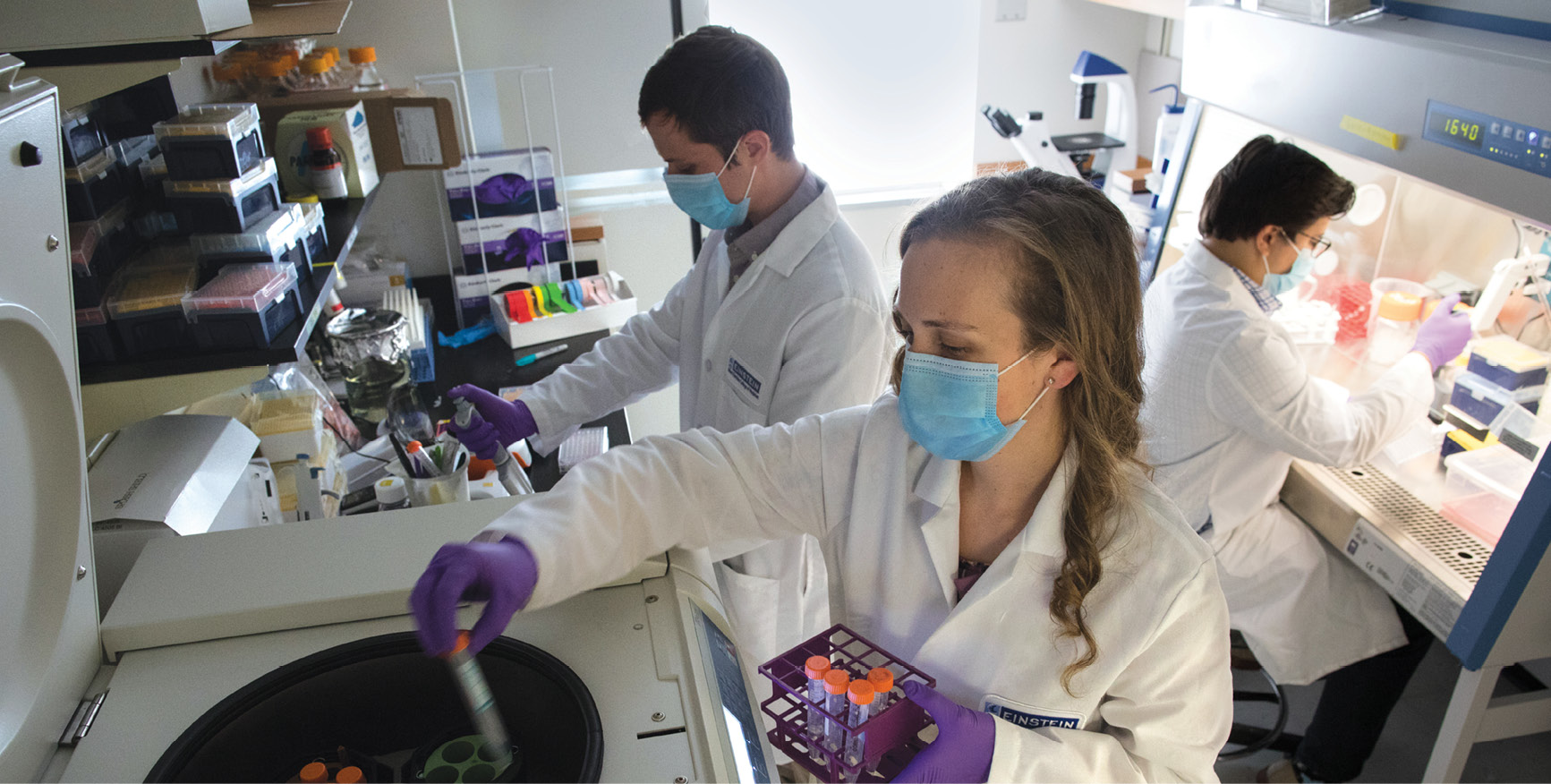

Both of the labs processed samples of donated blood from recovered COVID-19 patients—which came in at all hours—to separate out the serum, the part of the blood that contains antibodies.

The three students had one big advantage in developing the test: “Montefiore Health System unfortunately was at the epicenter of the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States,” Dr. Chandran says. “But as a result, Montefiore was able to give us a plentiful supply of the sera we needed to validate the test.”

Mr. Malonis, with others in the Lai lab, produced large quantities of spike protein by inserting a gene into cells grown in tissue culture. As soon as he could isolate and purify a batch, he would deliver it to Ms. Wirchnianski and Mr. Bortz, who would use it to test hundreds of patient-serum samples.

“As a small academic lab, this was something we were not used to,” Mr. Malonis continues. “What was exciting is that it felt like we were part of a large effort at Einstein, one of many labs that were focused and determined. It was something unique that I had never experienced before in my training.”

Mr. Bortz agrees. “This has been an amazing learning experience, finding out what it takes to mobilize such a huge effort, to shut everything down and then build a test for detecting antibodies against a virus we’re not familiar with,” he says.

The successfully validated test is now being used in Montefiore’s clinical pathology lab. “That’s not something we always think about on the research side,” Mr. Bortz says. “It has given us a different perspective on the types of experiments we do in our day-to-day work, and makes me wonder how we can commit to being more clinically relevant or useful during a pandemic situation.”

Ms. Wirchnianski says that her work on the coronavirus antibody test has helped people understand why virus research is important. “My family used to ask, ‘What do you do in the lab all day?’ Now that the coronavirus is mainstream news they say, ‘OK, I get it. What you do is actually useful,’” she says with a laugh.