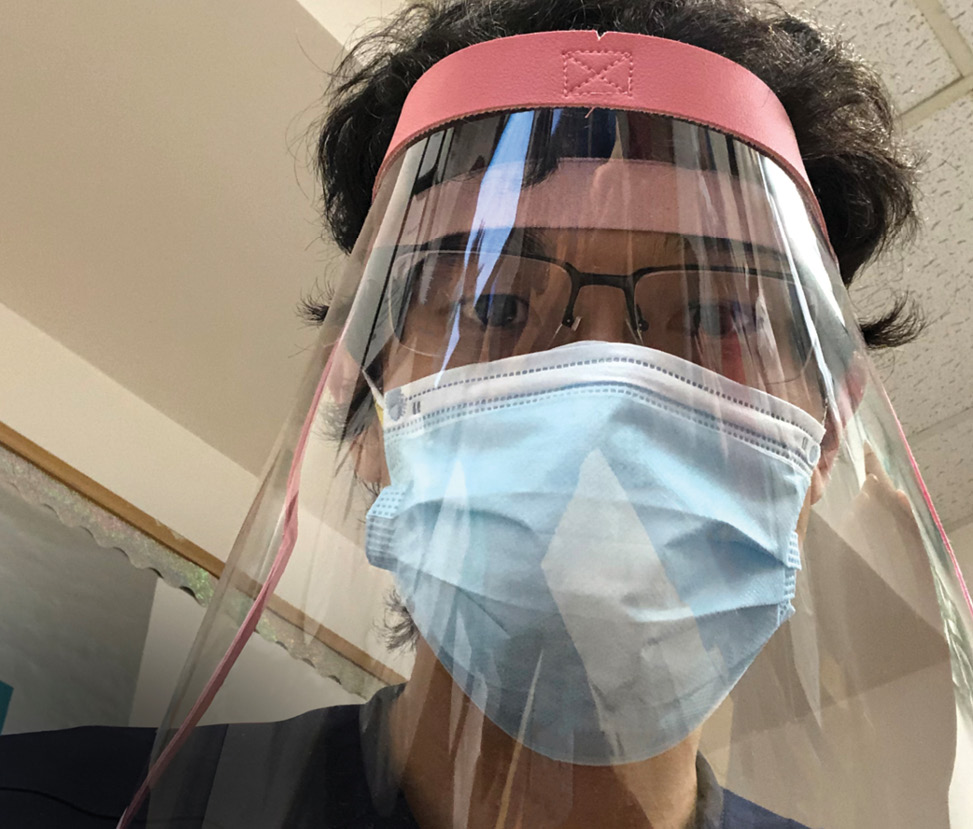

Einstein graduate Benjamin Liu, M.D. wears a face mask and face shield inside Weiler Hospital last spring.

Einstein graduate Benjamin Liu, M.D. wears a face mask and face shield inside Weiler Hospital last spring.

As thousands of COVID-19 patients were pouring into Bronx hospitals last spring, dozens of fourth-year med students opted to accept Einstein’s offer to let them graduate early to help battle the pandemic. There would be no restaurant celebrations or nights out with friends. Instead, many pivoted to help stressed healthcare workers cope with the increasing need for patient care at Montefiore. Here are three of their stories.

Vascular Surgery

Before starting her first shift as a physician last April, Dr. Morales Allende was terrified. COVID-19 was a mysterious illness that kept filling intensive care beds in the Bronx.

“I knew I was taking a risk,’” she says. “It was pretty scary. Some healthcare workers had gotten sick, and I didn’t know what to expect.” But the newly minted Einstein graduate—born in Argentina, raised in Queens—felt compelled to be there.

“We have a large immigrant and minority population in the Bronx,” she says. “I feel a great connection to them—I speak their language, I understand their culture, and I knew that people of color were being disproportionately affected by COVID-19. I wanted to advocate for them.”

Dr. Morales Allende completed a rotation in ambulatory medicine in mid-March, just as the pandemic began hitting the Bronx. She learned that Einstein was considering allowing fourth-years the chance to graduate early. After talking to friends, family, and professors about the risks and benefits, she decided to take the plunge.

Dr. Morales Allende quickly found herself on a COVID-19 floor at Weiler Hospital on the Einstein campus, part of a team consisting of one intern (radiology), one resident (anesthesiology), and one attending (medicine). She worked as a subintern, making rounds every morning, checking notes and labs to see how patients did overnight, examining them, and reporting back.

“Montefiore gave us a daily recap, explaining the latest protocols, what we were doing well, and what needed to change,” she recalls. “They told us things like, ‘This many patients were extubated today’ or ‘Tomorrow we are going to start giving steroids.’ It was a stimulating and ever-changing environment.”

Dr. Morales Allende especially remembers a patient she worked with for three weeks: a woman in her mid-60s with COVID-19 complicated by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The patient did well when first hospitalized, but later kept needing more and more oxygen. Since no visitors were allowed on COVID-19 floors, Dr. Morales Allende brought in an iPad so that the patient could communicate with her family.

“We were buddies, and I got to know her whole family after speaking to them every day,” Dr. Morales Allende says. “It was just so sad when I had to tell her, ‘We need to intubate you because you are getting worse.’

“I rolled in the iPad so she could tell her family what was going on. I wanted to stay hopeful and tell her she’d see her family later,” she says. “But the truth about intubation was that mortality rates were high. I knew she might be saying goodbye forever.” The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and died a little more than a week later.

As Dr. Morales Allende now immerses herself in her Montefiore surgery residency, she reflects on the past several months. “Everybody is still struggling,” she says. “But as much as you want to complain, it’s hard to do. At least you have your health, you know?”

Obstetrics and Gynecology

Getting sick from COVID-19 last spring made Dr. Alyssa Yeung all the more determined to battle the pandemic once she got better.

For one thing, she hoped her hard-won antibodies might protect her from reinfection. “That’s still to be determined, but I did feel more comfortable with the situation because I’d already gotten sick, and I wanted to help in whatever way possible,” she says. And she knew she was witnessing history and wanted to be a part of it.

In March Dr. Yeung had been completing her medicine subinternship at Jacobi Hospital before Einstein’s clinical education was suspended because of the pandemic. A couple of weeks later she fell ill with a mild case of the virus herself.

When she recovered, Dr. Yeung returned to Jacobi as a volunteer subintern on COVID-19 units. Physicians from many different specialties were coming together to help deal with the flood of patients. “I was on a team with a pediatrician and an obstetrician-gynecologist,” she says. “The internal medicine residents were very experienced and great at helping everyone out.

“In my first couple of days, two of my patients passed away,” she says. “Neither death was unexpected—they were extremely ill and we knew what the outcome was likely to be. They just happened sooner than the team was prepared for.”

Then came Einstein’s offer allowing fourth-years to graduate early, and she signed up to work as a new physician on COVID-19 floors at Montefiore’s Wakefield and Moses campuses.

Dr. Yeung says she felt “more responsibility, and it seemed more real” when she went into the hospital after graduating. She needed to adapt to a constantly evolving situation when it came to diagnosing and treating patients. “Loss of taste and smell was something that we were hearing about early on, and then those losses became official symptoms to look for,” Dr. Yeung says. “And the drug hydroxychloroquine, touted early on as a game-changer, turned out to be ineffective.”

Working with COVID-19 patients, says Dr. Yeung, helped her learn about workflow and other nonclinical aspects of medicine that she hadn’t focused on directly as a medical student. “I saw the additional steps involved in taking care of a patient—calling family members to update them, working with consult teams, arranging for discharge,” she says. “We get a taste of those things during medical school, but we don’t fully appreciate their importance until afterward.”

Now beginning her residency in obstetrics and gynecology at Montefiore, she says these past months have been “one of the best learning experiences a person could possibly get. I’m fortunate to have been a part of it. Medicine is changing right in front of our eyes.”