Jose Ortiz Jr., M.D. ’92, reflects on his time at Einstein, his path to professional success, and how to increase diversity in medicine

Jose Ortiz Jr., M.D., mentors a student in the Medical Experience Program at the Mayo Clinic Health System in Wisconsin.

Jose Ortiz Jr., M.D., mentors a student in the Medical Experience Program at the Mayo Clinic Health System in Wisconsin.

After moving to Eau Claire, Wisconsin, to join the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Jose Ortiz Jr. went on a hunting trip with his new colleagues. Later that day, he called a friend, a fellow Hispanic, back home in New York to tell him about his outing. “Hey, I shot this turkey,” Dr. Ortiz told his friend. “And he replied, in all seriousness, ‘Oh no! What did the guy do?’”

Dr. Ortiz got a good laugh out of that, but it was a sharp reminder that he was the odd man out. Hispanics like him were a rarity in rural Eau Claire County, where people of German and Norwegian descent predominate. Rather than withdraw, Dr. Ortiz reached out by befriending his coworkers, soaking in the culture, and visiting with locals to understand his new patients better.

The desire to make connections where none exist is a recurring motif in his 20-plus-year career, and the secret to his success. Today, he is an accomplished hand surgeon and chief of staff at Mayo’s branch in Eau Claire. Early on, however, one might have bet that he’d never even earn a medical degree.

Dr. Ortiz dropped out of college after his third year because he needed money more than he needed a diploma. Five years working at Yale University Hospital kindled his interest in orthopedics and provided the income he needed to resume his studies.

In 1988, he was accepted to Einstein, a triumph for a student of any background. But he recalls feeling out of place, academically and culturally. “That first year, I kept waiting for someone to come into class and tell me, ‘We made a mistake; you’re not supposed to be here,’” he says.

Determined to fit in and prove his worth, Dr. Ortiz won election as co–class president in each of his four years at Einstein. He sat on a search committee for an office of diversity dean, championed Shabbat elevators, established study groups and launched a student newspaper—efforts that exemplified Einstein’s commitment to social justice and service to community. By the time he graduated in 1992, he was among the select group of students elected to Alpha Omega Alpha, one of medicine’s foremost honor societies.

Not surprisingly, Dr. Ortiz chose to do his residency at New York University, which includes rotations through Bellevue Hospital, where patient diversity is the stuff of legend. “When I was chief resident, I remember getting a call about an emergency room patient complaining that air was causing her knee to hurt. ‘She’s crazy,’ the on-call resident told me. ‘I’ll notify psychiatry.’ I asked if she was from Puerto Rico, and when he said ‘Yes’ it all started to make sense. Some Puerto Ricans believe that when you give birth, air can get inside you and cause all sorts of health problems. Had I not known that, she would have been sent to the wrong physician—and who knows what would have happened to her. Too often, things get lost in translation.”

For Dr. Ortiz, this was a clear lesson that medicine needs more people of color. “One way to increase diversity is to get kids interested in healthcare as early as kindergarten, and to show it’s possible for them to become doctors,” he says.

“Another issue is that some minority college students aren’t ready for medical school,” Dr. Ortiz adds. “But it’s not enough for medical schools to say, ‘We can’t accept students who aren’t qualified.’ They must find ways to make those students ready.” To this end, he helped create the Medical Experience Program, a Mayo Clinic initiative that provides high school and college students with opportunities to shadow hospital physicians in a range of specialties. “You need to see it, touch it and feel it to understand that you can have it,” he says.

The cost of higher education is still another barrier to diversity, he says. “That’s a big stumbling block for a lot of us. Just weeks ago I paid off my last student loan—after more than 20 years in practice.”

Dr. Ortiz was fortunate to have a mentor in Pablo Vazquez-Seoane, M.D. (now at the South Texas Spinal Clinic), who encouraged him while at Einstein to establish himself as a leader, conduct research, and strive to close any gaps in skills between himself and others vying for a competitive residency such as orthopedics. “That ethic—to reach out and work hard—became my road map to

success,” he says.

He has advice for today’s Einstein students: “A while ago, when I was visiting Puerto Rico, I heard a physician say, ‘What you are, I once was; what I am, you will become.’ He meant that even if things are tough, you aren’t facing anything different from those who came before you. Don’t be discouraged. Have faith in yourself. The hardest thing about medical school is getting in. Once you’re here, all you have to do is apply yourself. You’ve already shown you have the aptitude to realize your dream to become a physician. That’s why they let you in.”

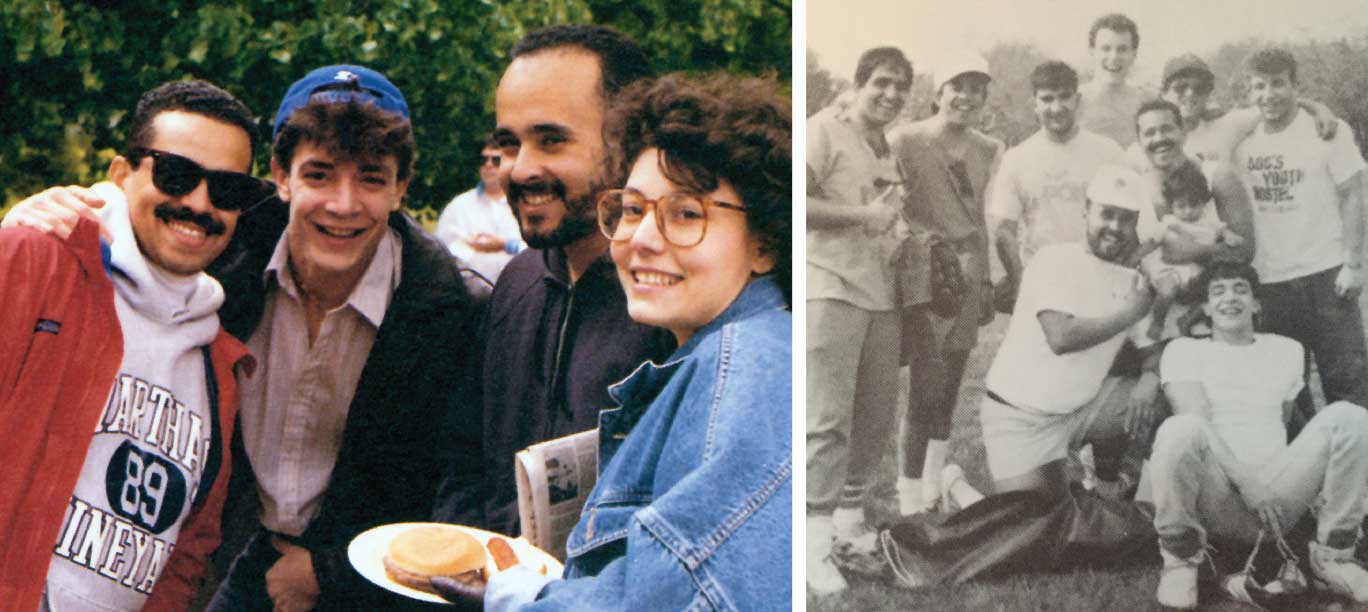

Above left: Class of 1992 Einstein friends enjoy a barbecue at the Falk Recreation Center in the early 1990s. From left are Dr. Ortiz, Raja M. Flores, William Alago Jr., and Sandy Ganea-Alago. Right: Dr. Ortiz, center, holds his baby son, Jose A. Ortiz III, who was the mascot for the Class of 1992 softball team. Standing, from left, are Sam Bakshian, Stewart Weinzimer, Maseith Moghaddasi, Samuel Abramovitz, Dov Linzer, and Allen Chernoff. Kneeling is William Alago Jr.; sitting is Raja Flores.

Above left: Class of 1992 Einstein friends enjoy a barbecue at the Falk Recreation Center in the early 1990s. From left are Dr. Ortiz, Raja M. Flores, William Alago Jr., and Sandy Ganea-Alago. Right: Dr. Ortiz, center, holds his baby son, Jose A. Ortiz III, who was the mascot for the Class of 1992 softball team. Standing, from left, are Sam Bakshian, Stewart Weinzimer, Maseith Moghaddasi, Samuel Abramovitz, Dov Linzer, and Allen Chernoff. Kneeling is William Alago Jr.; sitting is Raja Flores.